The experience of catching and enduring long COVID-19 has been a game-changer for Dave Nothstein, from Colorado Springs.

“I was a super go-getter” before catching it, he said. By his precise count, that was 665 days, or 22 months ago. Now he takes pleasure in more simple things. “I look forward to walking the dogs” each day, he said.

“My life changed, it went from full speed to just a crawl. That just blows your mind,” said the 53-year-old father of six, grandfather of four, and owner of two corgis.

Nothstein used to be the manager of parts for a luxury car dealership. But after catching what he thought was a really bad head cold in late 2021, he was zapped by brain fog, lack of energy and chest pain. And it just didn’t clear up.

For months his doctors struggled to figure out what was causing it, especially since he didn’t test positive for the coronavirus. Eventually, his doctor diagnosed him with long COVID.

“She's like, ‘Well, you don't have to have a flaming case of COVID to get long COVID, but at some point you had it or maybe not even enough to flag a test,’” Nothstein said.

These days, he feels better, but many symptoms remain, including persistent fatigue. Now months down the road, he’s had to switch to less strenuous IT work at the dealership and dial way back his favorite hobby, mountain biking.

But there’s renewed hope for people like Nothstein: research involving patients like him in Colorado.

Nothstein is a participant in the large national RECOVER study — looking at recovery after COVID. Research that came out of the program, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health, found those who were unvaccinated, got sick before the 2021 omicron strain, or who had COVID more than once were more likely to develop long COVID and had more severe cases.

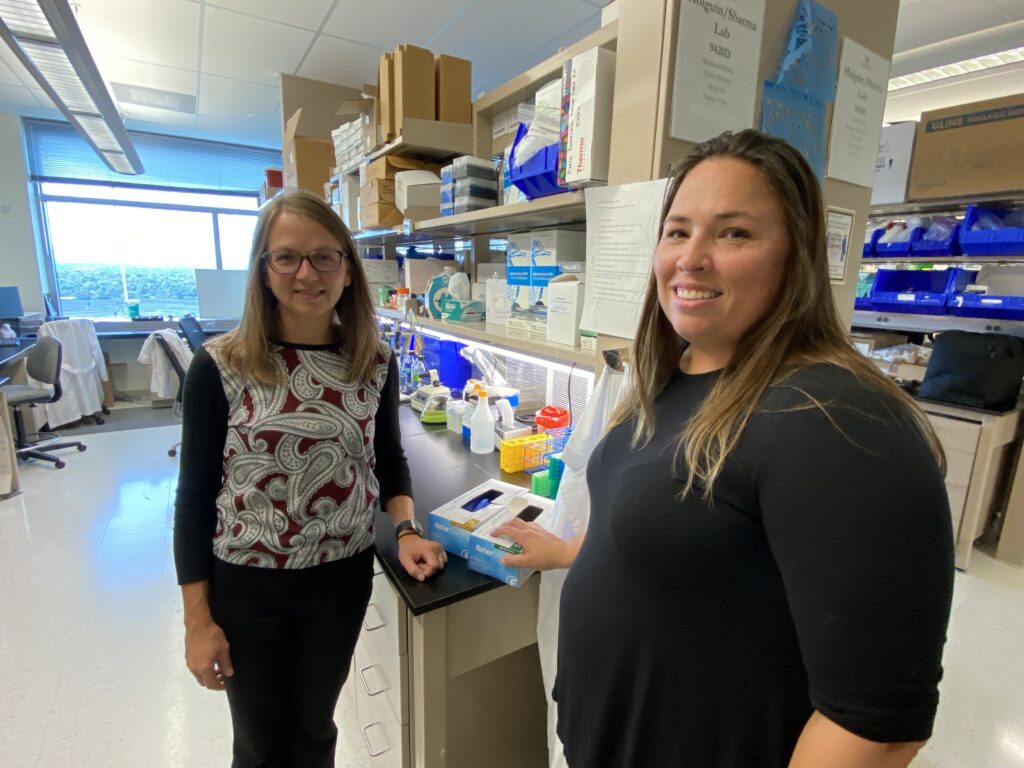

The outpatient clinics of the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (CCTSI) on the CU Anschutz campus was one of the sites where researchers worked.

“There's still a lot of Coloradans with long COVID,” said Dr. Sarah Jolley, the medical director of the UCHealth Post-COVID ICU Clinic.

She says perhaps 10 percent of people who’ve caught the virus develop chronic symptoms.

“Roughly between 250,000 to 600,000 Coloradans are living with long COVID currently,” Jolley said. “The risk for long COVID is still very much there and we don't really understand who gets it and why.”

One challenge is pinpointing what exact symptoms long COVID causes, said infectious disease Dr. Kristine Erlandson.

“A lot of the symptoms that people experience after COVID are common — in general like fatigue — and unfortunately a lot of people had fatigue even before we had COVID,” she said. “The RECOVER study will let us understand what risk factors might be directly related to COVID versus which risk factors are just common in the general population.”

But the research, which has now included more than 12,000 people nationwide, hopes to provide a basic understanding of long COVID. Researchers hope it will inform future studies.

Researchers examined more than 30 symptoms and identified 12 which set apart those with and without long COVID. That list includes: “post-exertional” malaise — after working out or exerting yourself mentally, fatigue, brain fog, dizziness, gastrointestinal symptoms, heart palpitations, issues with sexual desire, loss of smell or taste, thirst, chronic cough, chest pain and abnormal movements.

Nothstein said he’s experienced, to varying degrees, 10 of those symptoms, including the loss of smell. “Every single smell smelled like garbage,” he told researchers.

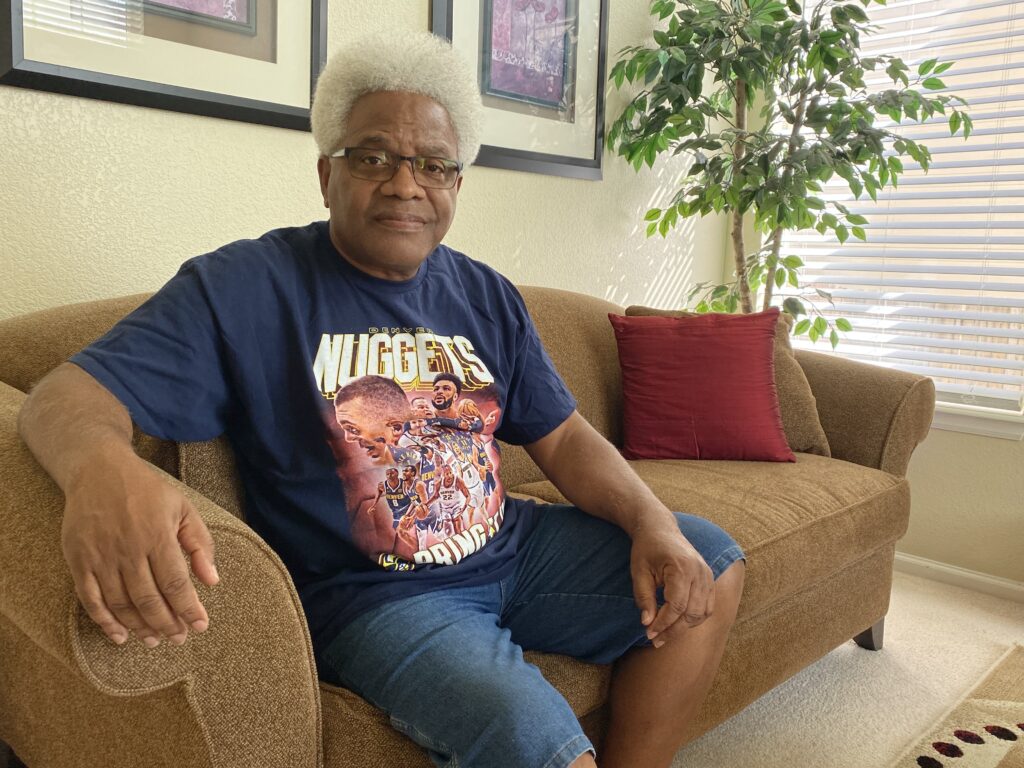

Another long COVID patient, Clarence Troutman, who wasn’t part of the study, said he experienced nine of those symptoms.

“It hits home: fatigue, dizziness, brain fog, still experiencing all of that along with some neuropathy,” Troutman said. Neuropathy is nerve damage causing pain, weakness, numbness or tingling. “It kind of comes and goes, and when it does come, it's pretty darn painful.”

Troutman, from Denver, caught the virus at the start of the pandemic. He was hospitalized for two months and on a ventilator. Now more than three years later, some illness lingers.

“I think if I could get my endurance back, my breathing would be better. A lot of other things will fall into place for me,” he said.

Troutman hopes the study sheds more light on long COVID.

“Absolutely, it's a long road,” he said, “but I do feel like it's getting better.”

Exercise and daily walks have been key to helping his conditions improve.

Nothstein said counseling has proved valuable for him. “It's very important to get someone to talk to,” he said. “Nobody likes to talk to a therapist, but I think that's one of the things that's helped me adjust.”

Researchers say the ongoing study will serve as a foundation for clinical trials — and, hopefully, treatments — to come. “Even though it's been three years and it feels like a long time, there is hope for treatments coming,” Jolley said.

Nothstein said he’s happy to be a part of it.

“I'm there to provide data, so hopefully we can find a cure or some way to lessen the effects and help others as well,” he said.

Researchers at CU Anschutz just got word that their program will receive millions in new funding for its work in Colorado.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced grant awards to nine sites around the country. Each will receive $1 million total for up to five years to support existing, multidisciplinary long COVID clinics across the country. The funding aims to expand access to comprehensive care for people with long COVID, particularly underserved, rural, vulnerable, and minority populations that are disproportionately impacted by the effects of the condition.

Meantime, both Jolley and Erlandson recommend people get vaccinated with the reformulated COVID-19 vaccine that is now available. They say research has shown vaccination protects not just against severe disease, but also against long COVID.

“The risk of long COVID seems to be decreased with vaccination,” said Erlandson. She advised that people can protect themselves by staying up to date on vaccines.

Jolley urged people to stay vigilant, especially as cases and hospitalizations have been rising in Colorado and nationally in recent weeks. She encouraged “minimizing your risk as you can because that risk is there and we don't know a way to stop or prevent fully yet.”