The steep slopes around the high country town of Dillon are draped with evergreen forests and streaked with golden aspen groves in the fall. Those endless woods are the domain of U.S. Forest Service supervisor Scott Fitzwilliams.

“I think Summit County is 86 percent national forest,” Fitzwilliams explained on a recent weekday. “Pretty much everything you see is National Forest.”

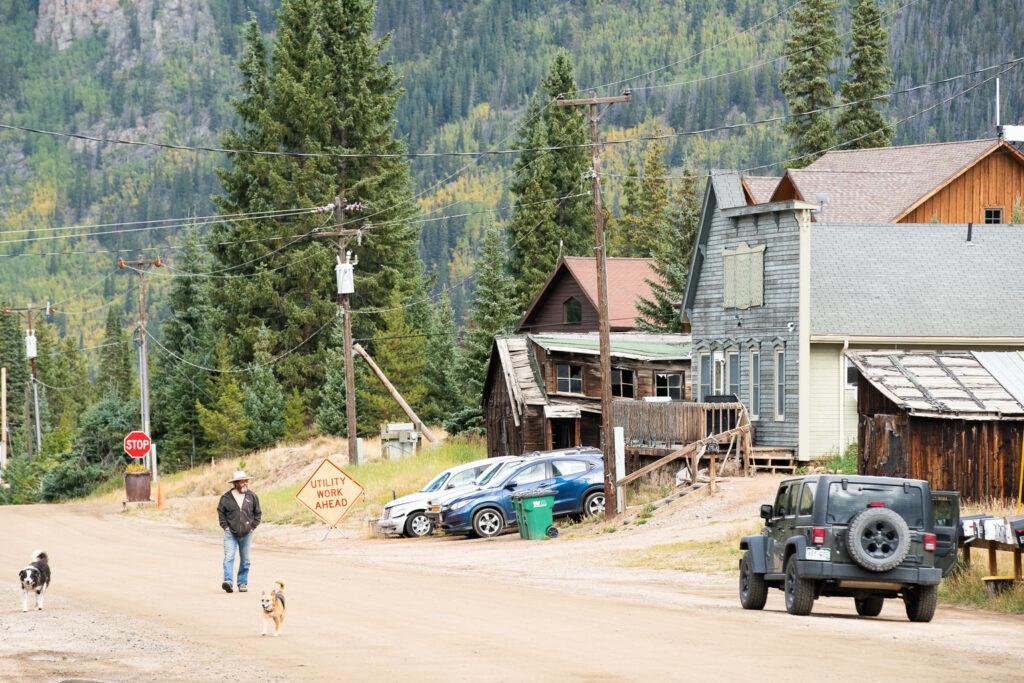

Fitzwilliams was surveying the pristine mountainsides from a much more mundane piece of land: 11 acres of sparse woods dotted with aging cottages, sheds and shipping containers. The Forest Service compound, sometimes known as a “boneyard,” has occupied a hilltop above Dillon Reservoir since the 1960s.

It’s home to not just equipment but also to people. About 20 employees of the Forest Service live here in peak season; the cabins rent for a relatively affordable $1,200 a month and come with excellent views, if little else.

“It is not the Taj Mahal. It is not the Regis, that's for sure,” said Fitzwilliams, who heads the White River National Forest. “These are pretty primitive, and we need to improve it. We're asking a lot for folks to live in these kind of conditions at 9,000 feet elevation in the middle of winter.”

But the service is lucky to even have this option for its employees. Housing is so hard to find here that it’s creating labor shortages throughout Summit County. Facing the reality of exorbitant rent or beat-up housing in these mountain towns — or maybe exorbitant rent for beat-up housing — job candidates are turning down coveted posts with the Forest Service.

“People are declining permanent job offers at more than 56 percent,” Fitzwilliams said. “More than half of the time we offer a job, people are saying ‘I can't. Would love to, but I can't afford it. I need housing.’”

USFS doesn’t have money, but it has land

The Forest Service doesn’t have the money to solve its housing problem, Fitzwilliams said. But it’s got something else that could help: land like this.

The agency is about to sign a lease to allow a developer to transform the hilltop property. The fire engine bay, the offices and the storage areas will all be rebuilt to modern standards. And just downslope will come the biggest change of all — an entire residential neighborhood of more than 150 units.

“Multi-story buildings with housing units of one-, two- and three-bedroom configurations mixed in with some green space and a community center and public transit and a rec path coming through,” said Anna Bengtson, land conveyance program manager for the national forest.

A handful of the residences — which may be apartments or condos — will be reserved for Forest Service staff, replacing the existing cabins. But the rest will operate as affordable housing, open for applications from middle-income workers like teachers and firefighters.

The project has millions of dollars of backing from the state and local governments, and it will be built by the private developer Servitas. Summit County will lease the land from the Forest Service for 50 years, but will provide housing for USFS staffers instead of paying rent to the agency.

“It really is an innovative project. It's the first in the nation,” said Summit County Commissioner Tamara Pogue.

Servitas could break ground on the roughly $100 million project next spring or summer, with construction expected to take about two years.

This all started in D.C.

It’s taken a literal act of Congress to make the project happen — the 2018 Farm Bill, to be precise. Federal lawmakers included a provision that authorized the Forest Service to lease out a strictly limited selection of its land for housing and other purposes.

Five years later, Dillon is set to be the first place it happens.

“Frankly, it's going to be beautiful, because the site is epic,” said Garrett Scharton, an executive with Servitas. “Any other developer would absolutely put $5 million condos on this site … Summit County and the Forest Service and Dillon have decided to give back to the local community for essentially locals-only housing.”

In some ways, the project is simpler than other developments. There’s no need for a zoning hearing where local opponents might slow the project, since the U.S. Forest Service controls the land. And the agency does have experience building its own housing.

But it’s the first time that USFS has allowed a public-facing community on its land — and, indeed, it’s rare for any federal agency besides the military to be so directly involved in a project like this.

“The federal government as a counterparty in any transaction can be intimidating,” Scharton said. But the project has gone smoothly, with USFS leaders seeming to put their full weight behind it, he said, adding: “And that's because their goals are our goals and their goals are the county's goals. Their goals are the town of Dillon's goals.”

Could more USFS land be used for housing?

The project is drawing national attention, a sign of how many other rural and resort communities are desperate for land for housing.

“In fact, a few weeks ago we hosted a delegation of congressional staff from Missouri, Montana — I mean, all over the place,” Pogue said.

Despite the widespread interest, these kinds of developments won’t be turning Colorado campgrounds into condos, Fitzwilliams stressed. For example, in the White River National Forest, there are only a handful of appropriate sites, all of them concentrated in areas that are already developed for the agency’s administrative uses, Fitzwilliams said.

“It might be 40, 50 acres that we would consider something like this, and the forest is 2.4 million. So, obviously, a very small part of it,” he added.

The law mostly allows the Forest Service to lease out sites that were bought or used for administrative purposes like storage, housing and fire prevention. It also allows for the leasing of a limited number of “isolated, undeveloped parcels” under 40 acres, which USFS officials say is meant to apply to properties similar to the administrative sites.

So far, the Dillon project has been uncontroversial — perhaps because the site has already been developed to an extent. But some officials would like the Forest Service to open up a broader range of sites for housing.

“You still want to have it close to infrastructure and water and sewer and not have your costs skyrocket because it's too far away from that, but I think there's a ton of parcels across Western Colorado and in many parts of the state that are currently forested or that need physical improvement to be developed. This is a great test case for that,” said state Sen. Dylan Roberts, a Democrat from Avon.

He added: “We’re not going far out into the forest and clear-cutting a ton of trees,” noting that any projects will be locally driven. Other early discussions have happened about sites in Eagle, Chaffee and Routt counties and near the towns of Minturn and Basalt, according to Roberts and Fitzwilliams.

Commissioner Pogue suggested looking at properties that may be wooded but less-than-pristine, especially ones that have been hemmed in by roads and development. But she knows that could run the risk of public backlash.

“Some of the toughest fights in Summit County are the ones where you have a need for affordable housing, but there's also a need for open space. And so there's always a tension,” she said.

Marcus Selig, chief conservation officer at the National Forest Foundation, said that the Forest Service should be — and will be — careful in choosing future properties.

“It's great because it creates another way to utilize our land, but it also makes it that much more challenging to manage. And so I think there could be potentially positives to it, but I think that it could also lead to a lot of challenges from a management perspective as well,” he said.

There’s one more catch: The Forest Service’s ability to do these leases expires on Oct. 1. The Dillon project can still move forward if its lease is signed on time, but the door is closing on other potential projects, at least until Congress reauthorizes the practice.

Rep. Joe Neguse, a Democrat, has introduced the Forest Service Flexible Housing Partnerships Act, which would extend the agency’s leasing authority until 2028 and make some other changes, like allowing for 100-year leases instead of 50-year leases. Democratic Sen. Michael Bennet and Republican Rep. Lauren Boebert also have signaled approval of the measure.

Versions of the bill are pending in both the Republican-controlled House and the Democrat-controlled Senate — where, for now, the threat of a government shutdown has overshadowed all else.

Editor's Note: Anna Bengtson's name was originally misspelled in a photo caption. It has been corrected.