On a sunny early September afternoon, longtime San Luis resident Donna Madrid Hernandez sat at a shaded picnic table in the town park. She threaded about a foot of blue wool fiber onto an embroidery needle as she prepared to fill in the sky above a white building with red trim already sewn onto a large rectangle of fabric.

“This is a very simple stitch,” she said. “You get a long piece, you start at one end… you stretch it out... Then you take your needle and go under the piece that you stretched out…You're just going to go overlapping that long piece that you started, and it'll take you back to the end and you start it all over again.”

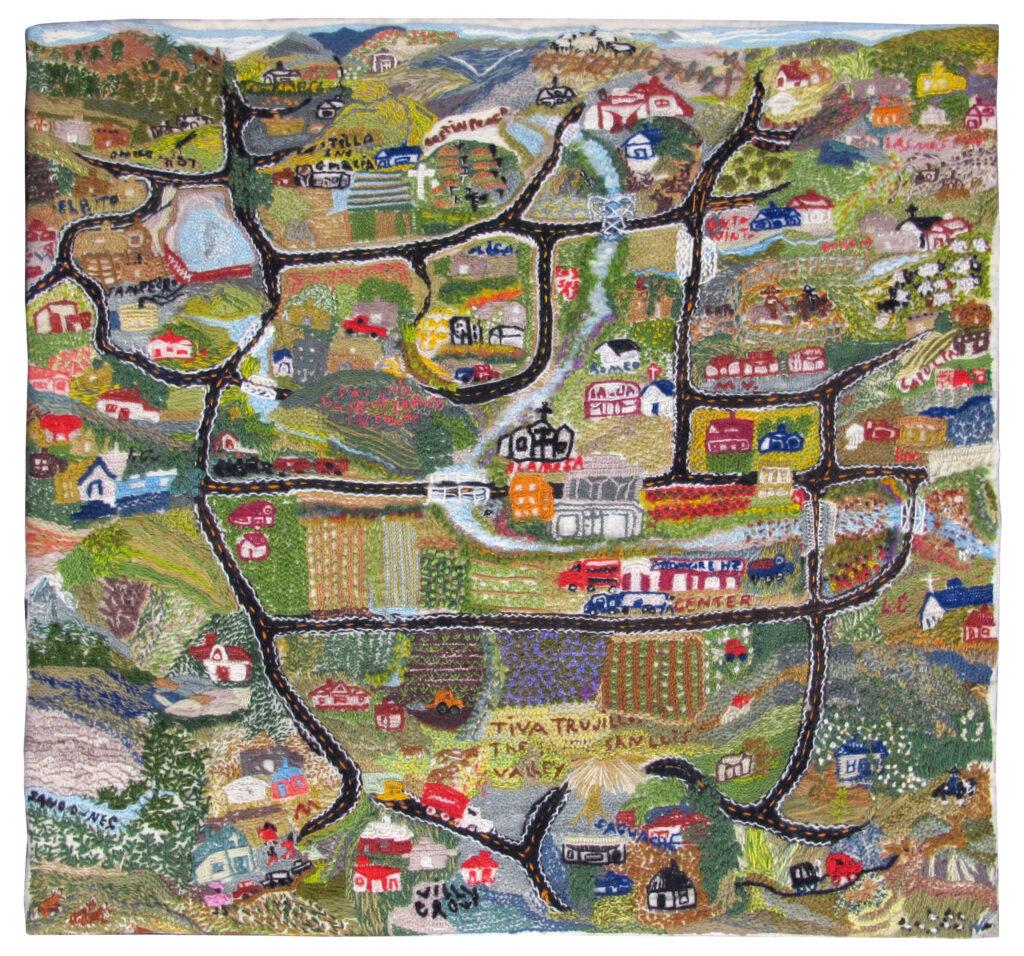

Colcha embroidery is traditionally used to decorate bedspreads, clothing and table linens with images like flowers and birds, but some women in the San Luis Valley use it in a different way — to capture stories of the region. During the last five decades they’ve stitched farm scenes, bits of everyday life, and even a map of the valley.

Hernandez used a photo of the building she’s illustrating to create the design of the historic Concilio Superior in Antonito, across the valley from San Luis. The building houses a Hispanic mutual aid society that her father and grandfather belonged to.

“They backed their people,”she said. “They were there for them in hardships. When they didn't have money, they'd help them out. When they had losses in their family, they were there to support them financially as well as emotionally - what they were going through.”

When finished, Hernandez will have covered every inch of the fabric with embroidery. The detailed work can take hundreds of hours or more.

Using embroidery to capture the stories of a place

Artist Adrienne Garbini learned the craft when she moved to the valley nine years ago. “These pieces represent family members, they represent stories, they represent memories, they represent the place,” she said. They are just these beautiful celebrations of the valley and of people's experiences.”

Garbini helped curate an exhibit of San Luis Valley colcha embroidery currently on display at the Arvada Center near Denver. She said the pictorial and narrative style is part of what makes the embroidery from the valley special.

“A lot of the time people are depicting their very core memories in these pieces,” she said. “Things that happened to them as a child, things that they experience that may not be part of their everyday life anymore.”

That’s the case for Patsy Garcia, a lifelong resident of Saguache in the northern part of the valley, who started making colcha embroidery decades ago.

She said her most recent piece depicts her father’s work as a sheep shearer during the 1940s. She described a man kneeling by a sheep with his clippers, “then I have a sack where they used to get the balls of wool and press it in the bag and then tie the bag and it's a big huge bag of wool and it's just beautiful.”

Missing artwork, stolen legacies

But there’s a part of the history of colcha in the San Luis valley that isn’t so beautiful.

In the 1970s a now defunct Denver-based foundation brought an economic development program to the valley aimed at helping rural women by generating income through cottage industry, according to Garcia and Garbini. The organization set up colcha embroidery workshops there and then arranged exhibits in bigger cities around the country, including at the Arvada Center. Garcia said a number of her pieces were among those included in the various art shows. But the colchas went to the big city and vanished.

“We made pictures that we never saw again,” she said. “They were taken from us and we never saw them. So the money that we were supposed to make wasn’t happening.”

Some of Judy Vigil's colchas went missing too. She grew up in the San Luis Valley and lives in Pueblo now.

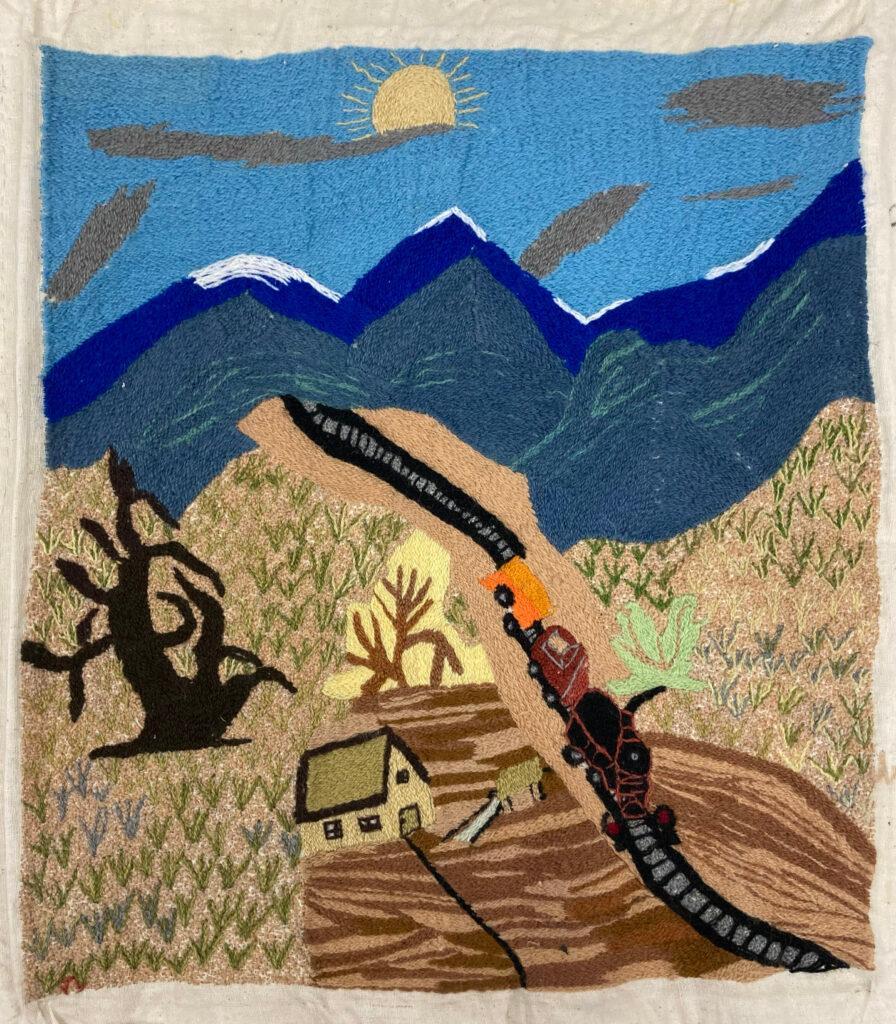

A colcha embroidery by Judy Vigil shows a train in the San Luis Valley.

A colcha embroidery by Judy Vigil showing the San Luis Clinic.

A colcha embroidery by Judy Vigil is titled "My Cabin."

“It was always on my mind,” she said. “Whatever happened to my beautiful pictures? My work that I put a lot of energy into it and a lot of pride. I do take pride in my work.”

An unknown number of pieces by the San Luis Valley colcha artisans disappeared according to Garbini, adding that the women were not invited to the shows or included in the planning. Several received a few dollars compensation for the sale of their work, but most got nothing and never got an accounting of where their work was, she said.

Vigil still embroiders, and so do others who saw their work vanish. But some of the women who were part of the original program gave up doing colcha as a result of that experience.

Artwork returned, a craft shared

When Garbini heard about the missing art, she connected with the Arvada Center, one of the original art show venues. The staff there discovered nine pieces in storage that the city had purchased all those years ago. Those are now hanging in the current show and will be returned to the artists and their families. After decades, Vigil will get some of her work back.

“It was a big shock to me,” she said. “I'm happy that they found them, I didn't even know where they were. They were gone for the longest time. And I know there's still a lot more out there.”

Garbini and others are researching where the other missing colchas may have ended up. Because so many years have passed since the pieces went missing, Garbini said she imagines that whoever has them now may not know where they came from.

“So often it is the case that when we are acting with good intentions but we are disconnected from the communities,” she said, “that we don't have access to the realities of those stories.”

One collector, however, has already come forward to return a piece.

Meanwhile some of the San Luis Valley artisans are happy to have their work on display in Arvada. They are also pleased to be sharing the craft with a new generation.

Hernandez said she’s taught colcha at schools and libraries in Fort Garland and Alamosa. “Those kids were awesome,” she said. “One young man finished his project and he was so proud of it. The other kids worked on theirs and they were excited about it too.”

There’s also a colcha group that meets regularly in San Luis, Hernandez said, “If anybody comes in and they want to learn, we sit them down and we start them up.”

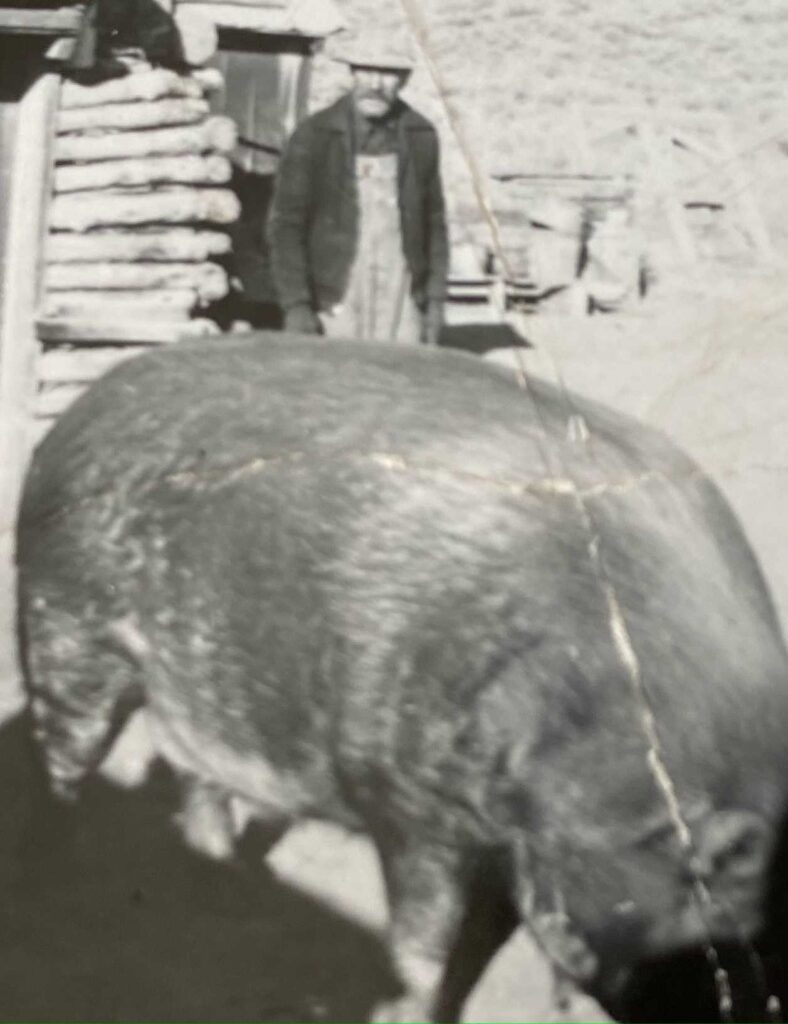

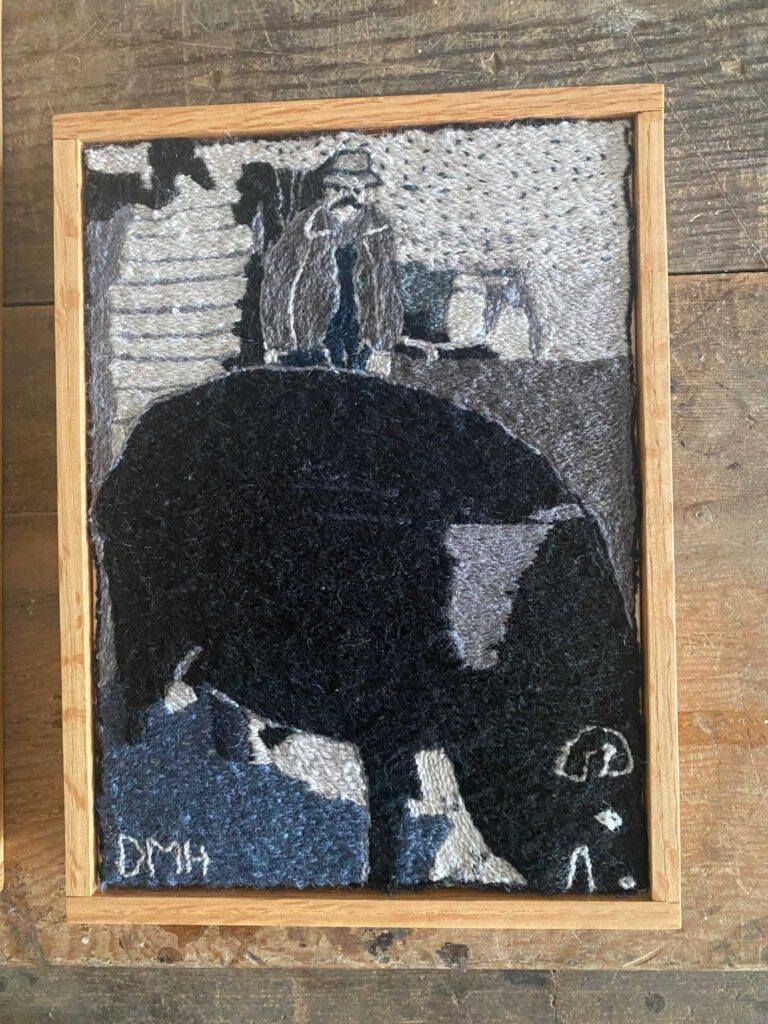

The photograph Donna Madrid Hernandez used to create a colcha embroider of her grandfather who raised pigs in San Luis.

This one was my grandfather. He used to raise huge pigs. His pigs were so big that they used to have to bring the wrecker trucks in to pick them up so they could clean them..… this picture was taken at our house right here on Main Street. My grandfather built that house, and this was in his backyard, and it was close to the mountain here. So he would take his pigs out, and he'd get them fed and stuff. And he had corrals where he would put the pigs. They took this picture one morning. (And I decided) I'm going to (make a colcha from) this one. And people have offered to buy it, and I won't sell it because it means so much to me.

-Donna Madrid Hernandez

Editor's Note: The Arvada Center is a financial supporter of CPR, but has no editorial influence.