Colorado is getting a fuller picture of a dark era in state history. At around the turn of the 20th Century the federal government funded institutions to try to strip children of their Indigenous identities. On Tuesday, state archaeologist Holly Norton released the results of her team’s year-long investigation into the practices of the schools. The research was mandated by the state legislature in 2022.

The state’s investigation offers more depth on the extent of this harmful historical practice in Colorado, which took place throughout the U.S. and Canada and was described in a federal report in May 2022.

"It's history that needs to be told," said Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren. Many Navajo children were at Colorado institutions. "There are times when we advocate for our communities and our nations, and all we want is to be part of a society that can be able to take care of themselves, but in order to do that, we have got to acknowledge the past. Native people, Ute people, Navajo people, have sacrificed so much."

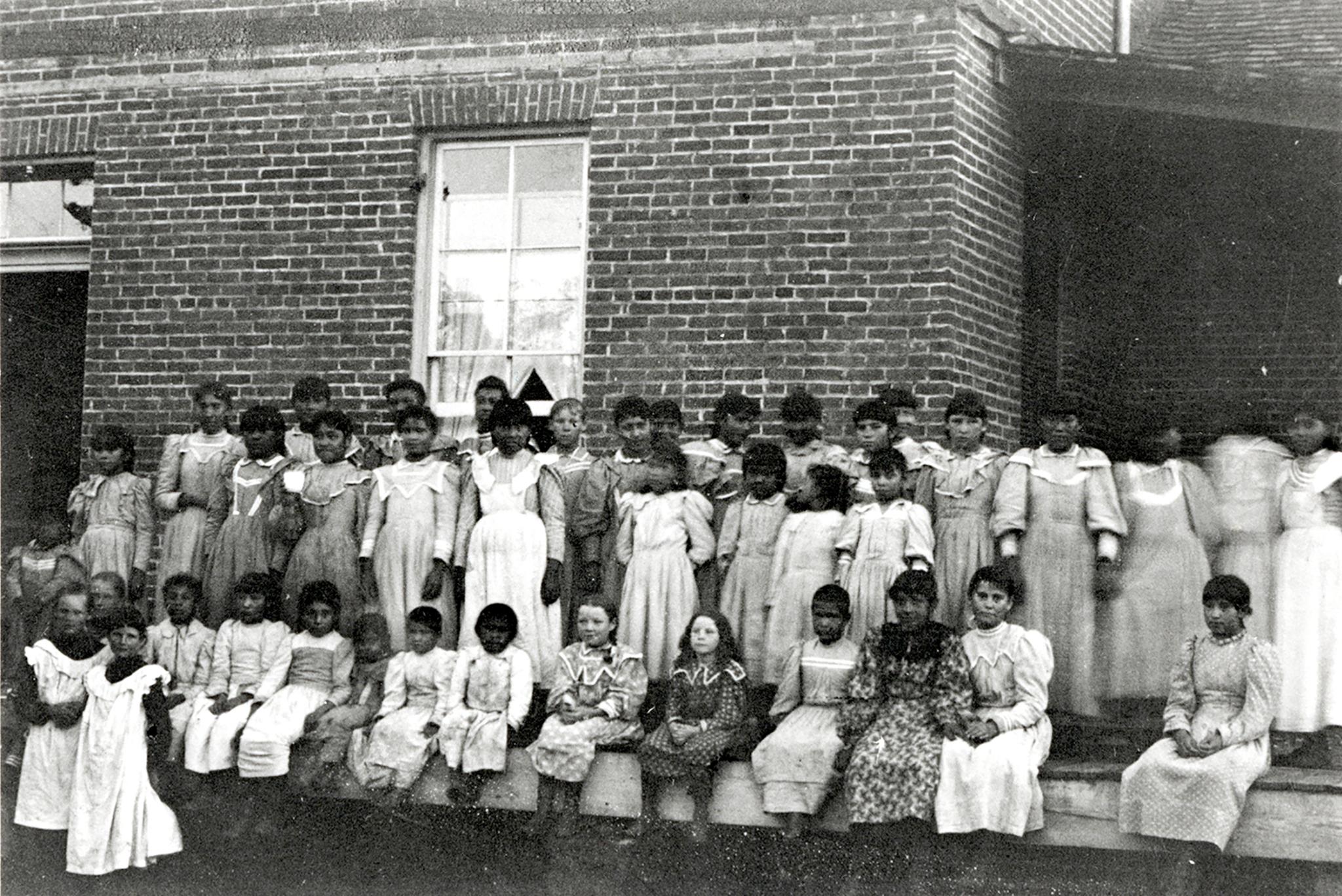

History Colorado’s research team has identified nine institutions in the state that attempted to assimilate students. The two most prominent, in Grand Junction and at Fort Lewis near Durango, were boarding schools designed to house children from various Ute bands. However, Norton lays out how the Utes in Colorado were very distrustful of the schools and were largely successful in resisting efforts to enroll their children.

Instead, the institutions in Colorado brought in children from throughout the region. The overwhelming majority of students were Navajo. However, the History Colorado research found that in some cases, school officials categorized students as Navajo even though they may have been Mexican, and were not Indigenous, in order to pad the school’s enrollment numbers and gain more federal funding.

In Grand Junction, in addition to more than 100 Navajo children, there were dozens of Hopi, San Carlos Apache and Tohono O’odham children enrolled.

In all, Norton’s team estimates that as many as 1,100 children attended the Fort Lewis Indian Boarding School from about 1892 to 1909. Norton’s team found evidence that 31 students died there. They additionally found evidence that 37 people died at the Grand Junction institution, sometimes called the Teller Institute, including one teacher.

The Fort Lewis Indian Boarding School was on the site of the former Fort Lewis military post in Hesperus, Colorado. The site later became the campus for Fort Lewis College, though the college moved mid-century to its current home in Durango. The Grand Junction school was on what is today state-owned land.

The research team found distinctions between the boarding school experience in Colorado and how it played out in the rest of the country. In Colorado, schools started operating later than in other states, and they were not predominantly governed by the Christian church.

But, “The goal of assimilation remained the same,” the report states. “Education in this context was not about reading, writing, and arithmetic, but about severing Native people’s ties to their traditional knowledge systems, and instilling in them Euro-American ideals of religion, labor, private property, and even family dynamics.

“For most of the existence of the United States, education sat alongside physical domination, such as warfare, as a means of eradicating Native peoples,” Norton wrote.

However, while the federal education system was damaging, it never achieved the goal of eradication. And today, people involved with the investigation say the preferences of tribal nations should dictate how the state approaches healing from and reconciling its history with federal schools that targeted Indigenous children.

What healing and reconciliation could mean

Monday, Colorado Governor Jared Polis "privately showed his respect at the former site of the Indian Boarding school" at Fort Lewis, according to his staff. He also visited the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute tribal councils, related to the release of Norton’s report.

The governor’s office declined an interview about their discussions, and it’s not clear what steps the state may take next, though a statement from Polis says he is "committed to partnering with Tribal Nations and American Indian/Alaska Native communities affected as we work together to address the intergenerational trauma and harmful impacts of the boarding school era."

Norton’s team outlined proposed actions towards healing last month, focused on setting up tribal consultations over a period of years.

Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute tribal leadership declined to speak about the report in anticipation of its release Tuesday. In the past, Ute Mountain Ute Chairman Manuel Heart told CPR News that the state should try to help recover culture that was lost through forced assimilation.

Nygren said the Navajo Nation is not requesting anything specific at this point, but that what the tribe is fighting for is, "Really trying to revive our way of life, revive our language, revive our culture, so that generations to come can enjoy the language and the culture." Additionally, he said if the state wants to issue a formal apology for the boarding schools era, "I think our nation and our people would really appreciate it." He does not plan to ask for an apology, though.

State Representative Barbara McLachlan represents southwest Colorado and sponsored the legislation that mandated and paid for the state’s research. She said Monday that funding for further research, mental health care on reservations, or other services, “should never be off the table.” She said she plans to consult further with the tribes to figure out what they want before deciding whether she will bring forward more legislation, including more requests for funding.

One potential proposal would require Indigenous history be taught more fully in Colorado’s public schools. Ernest House Jr., the executive director of Colorado’s Commission of Indian Affairs for most of the period from 2005-2018, is advocating for that. House is a Ute Mountain Ute tribal member, and his father served as the tribe’s chairman and attended a federally mandated on-reservation boarding school.

House said a mandate for more public education about Indigenous people’s history in Colorado is, “still one thing that we have not been able to require in the state.” He also wants the legislature and the governor to fund further research around boarding schools. “I think we need to make sure to continue this conversation in some form or fashion,” House added.

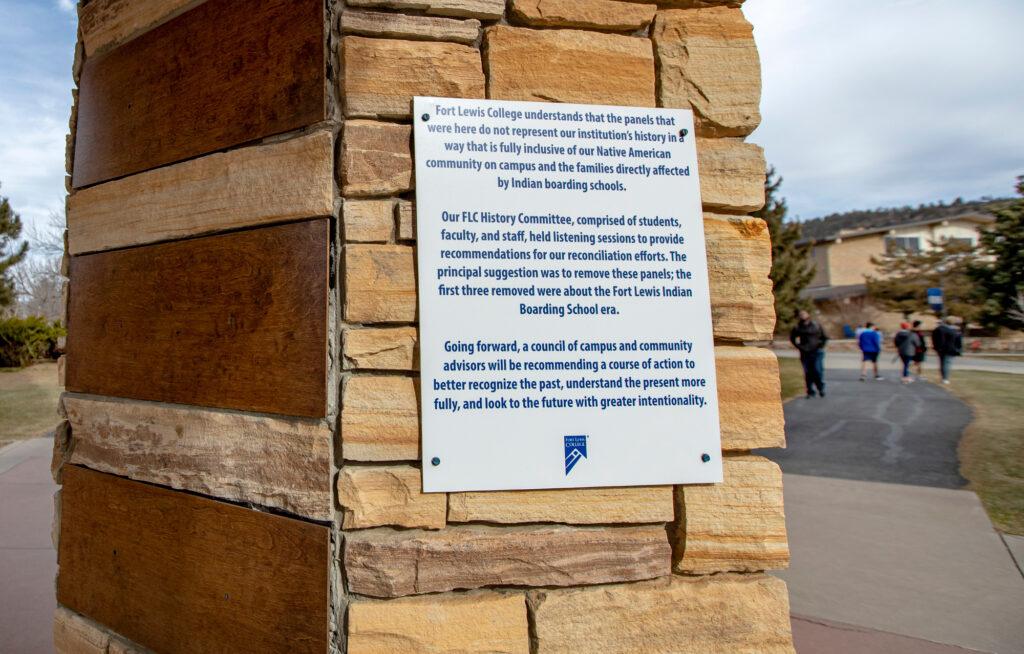

In her report, Norton acknowledged that Fort Lewis College, which was established on Indigenous lands that include the campus of the former boarding school, has been working for longer than the state to understand the legacy of boarding schools and to take steps aimed at healing and reconciliation. That work started in earnest five years ago. Since that time, Fort Lewis College has been a national leader in defining what it means to be an official Native American-Serving Institution.

College President Tom Stritikus said Monday that the release of Norton’s report puts the historical record in one centralized place and encourages the college to “double down” on its mission to serve the Indigenous students of today. Forty-three percent of Fort Lewis’ students are Indigenous. Strikus said as the college has better defined how to be an inclusive campus “part of that inclusivity is just being honest with who you were and what responsibility that creates for the future.”

In August, the college’s board of trustees, which includes House, codified the school’s commitment to reconciliation. “That was an important step for us, because then this work lives beyond any individuals,” said Fort Lewis’ Vice President for Diversity Affairs Heather Shotton, who is a citizen of the Wichita & Affiliated Tribes and a Kiowa and Cheyenne descendent. “It lives beyond any specific leadership, and it becomes a part of the fabric of the institution and it holds us accountable.”

A few weeks ago, Stritikus and Shotton visited the Navajo Nation and spoke with the president and vice president about how the state’s findings from the boarding schools era influence the ways Fort Lewis College can best serve Navajo communities going forward, such as a new nursing program and an academic focus on business leadership. Fort Lewis has also started programs to teach Indigenous languages.

The school has also scheduled a November meeting of its tribal advisory council, which includes Ute and Navajo leaders, along with Alaska Native members. Stritikus said they will discuss whether they want to push for further legislation to investigate the boarding schools era from the perspectives of tribal members, in particular, since much of History Colorado’s research was based on official reports from white people who ran the boarding schools.

Shotton said that the state’s investigation, “Is long overdue, but I think one of the things that has been important for us is that it's always the right time to begin healing, and that we have the opportunity to shape and reshape what an institution of higher education can do, how it can be responsible to Indigenous people, and how it can be in good relationship with place and with tribal nations.”

Stritikus emphasizes that the goals of the boarding schools era across America, to vanquish Indigenous cultures and communities, were not accomplished. “You walk on our campus and you see the exact opposite of that,” he said. “You see an absolute dynamic environment, you see the power of our students, you see all of the things that they're trying to do both for themselves and for their communities.”

Life at the institutions

The History Colorado research team details sexual abuse carried out by a long-serving superintendent of the Fort Lewis school. For years, Thomas Breen abused children and staff. He was accused of impregnating some, and then sending them away from campus. Breen’s actions were exposed a century ago by the Denver Post. He was superintendent for nearly a decade before he was fired.

“The story of the Fort Lewis Indian Boarding School under Breen and the failure of the federal government to protect Native children is a microcosm of the deep neglect that was visited on the children by the government throughout the entirety of the school system,” Norton writes.

She notes other examples of inhumanity brought on Indigenous children at these institutions. Students at Grand Junction reported physical abuse from the head teacher. Additionally, children were subjected to “neglect, unsanitary conditions, and poor nutrition that accounted for sicknesses that often swept across the schools.” That included outbreaks of tuberculosis and of trachoma, which blinded students.

House said his father spoke about his time in a boarding school as compared to his service later in the U.S. military. "He felt that going to the military was a very easy for him because he was used to it. It was something that he already knew. The drill sergeants weren't a big deal. They didn't really rattle him because he grew up in a boarding school framework," House said.

Nygren said people in his community, including his grandmother, have also shared "traumatic" stories with him. "I just can't imagine having your kids torn away from you, and just to know that your kid never came home is a tough thing to think about, when you put yourself in their shoes."

Children as young as kindergarten were brought to the institutions. Most often, they enrolled in assimilation schools in Colorado because of active recruiting by federal and school officials. And, “While parents had legal rights, and were supposed to provide consent for their children to attend school, the consent was often coerced and ill-informed,” Norton writes, some children were also kidnapped and brought to the institutions.

Once enrolled, students had their hair cut and Native names replaced with Anglo-American names.

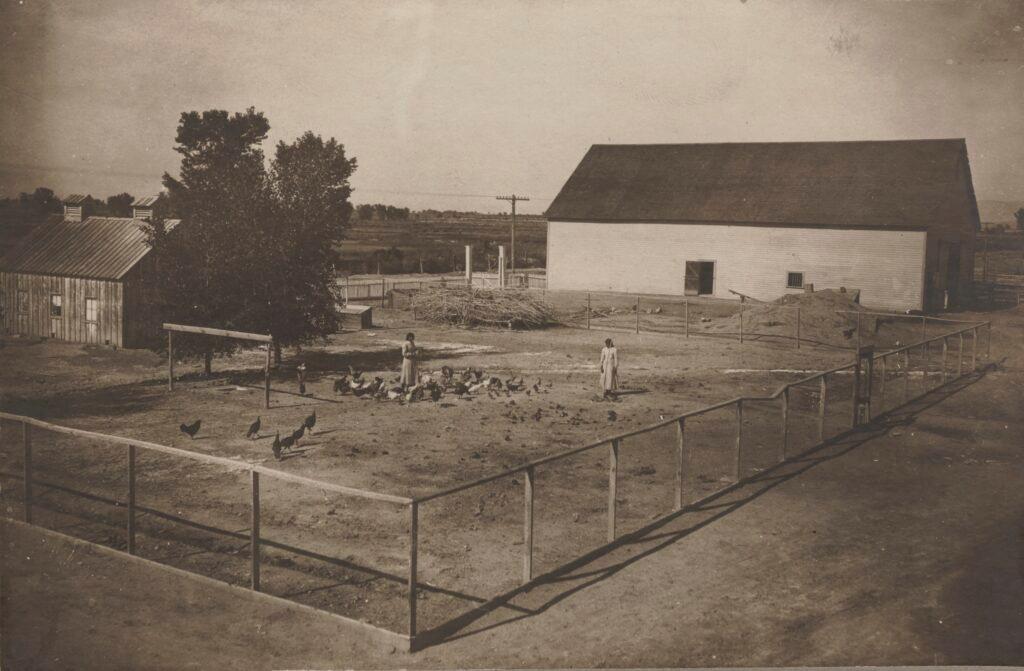

The people in charge had almost full autonomy, which means there are inconsistencies in how the institutions were run and what life was like for the children. Norton notes there were some positive moments for students on campuses. But consistently, children worked to keep the institutions running. They were also forced to work off campus, some as far away as Rocky Ford on the Eastern Plains, where they did agricultural labor.

While the goal was assimilation into white Anglo culture, the Indigenous children were not given the same opportunities as their white counterparts.

“It was never expected or encouraged that Native children would enter mainstream society to compete economically with their white peers. Instead, they were meant to compete with other marginalized groups as laborers and domestic servants,” Norton writes.

Starting in the early 20th Century, the U.S. government increasingly favored on-reservation boarding schools, and phased out institutions like the ones in Grand Junction and Fort Lewis.

The state’s investigation

It took many years for the state to arrive at a place where it was ready to document and confront this history, according to House. He said throughout his work in state government, he saw resistance to having difficult conversations about the boarding schools and other dark chapters of Colorado’s history with Indigenous communities.

What’s different now, he says, is, “Not only have we seen a lot of legislation that has opened up conversations to Indigenous communities, like higher education access and housing issues, and now the impacts of pandemics and healthcare overall. We've also seen the state expand in their tribal liaison positions for state agencies. All that has really opened up the opportunity to not only have these difficult conversations but also provide guidance around how to move forward.”

Norton’s research team received state legislative funding for one year. This allowed them to do extensive but not exhaustive research. They focused mostly on archival documents, particularly at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., and relied on reports and notations of people who were in charge of the schools. They also did geophysical examinations of the former boarding school sites. Among other things, they identified the boundaries of a cemetery on the grounds of the Fort Lewis school, which had not previously been known.

While it took a long time for the research to come to fruition, and while there is still much to be uncovered and more to be decided about future steps, House sees this period of history in the context of his people’s long presence in this area.

“Archeologists will tell you that the Utes have been in Colorado for the last 10,000 to 12,000 years. But if you ask me, and if you ask my elders in my tribal community, we'll say that we've been here in what we call Colorado since time immemorial,” he said. Through all those years, his people have had to be resilient.

“And so, as dark of a chapter as the boarding school era is,” he said, “if there's anything that continues to come to my top of mind each and every day, it’s resiliency.”

The full list of tribes whose children were identified as attending assimilation schools in Colorado includes: Apache, Aztec, Catawba, Cherokee, Hopi, Isleta Pueblo, Jicarilla Apache, Kaibab, Laguna Pueblo, Mescalero Apache, Mojave, Navajo, Paiute, Pima, Pueblo, Rancheritos Pueblo, San Carlos Apache, Shevit, Shoshone, Southern Ute, Tagua, Taos Pueblo, Tohono O’odham, Tonto Apache, Ute Mountain Ute, White Mountain Apache, Winnebago, Wyandotte, and Yuma.

The state has created a public comment form, through which individuals connected to this history can submit feedback and questions that will go directly to the History Colorado research team. Additionally, the public can come to the History Colorado Center in Denver Wednesday through Saturday, from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m., to access additional resources and research the history of the Federal Indian Boarding School Program.

Editor’s note: History Colorado is a financial supporter of Colorado Public Radio, but it has no control over the content of our journalism.