Twenty-five years after the murder of University of Wyoming student Matthew Shepard, a landmark play created in the wake of the anti-gay hate crime is returning to the stage in Colorado. And it’s still sparking conversation.

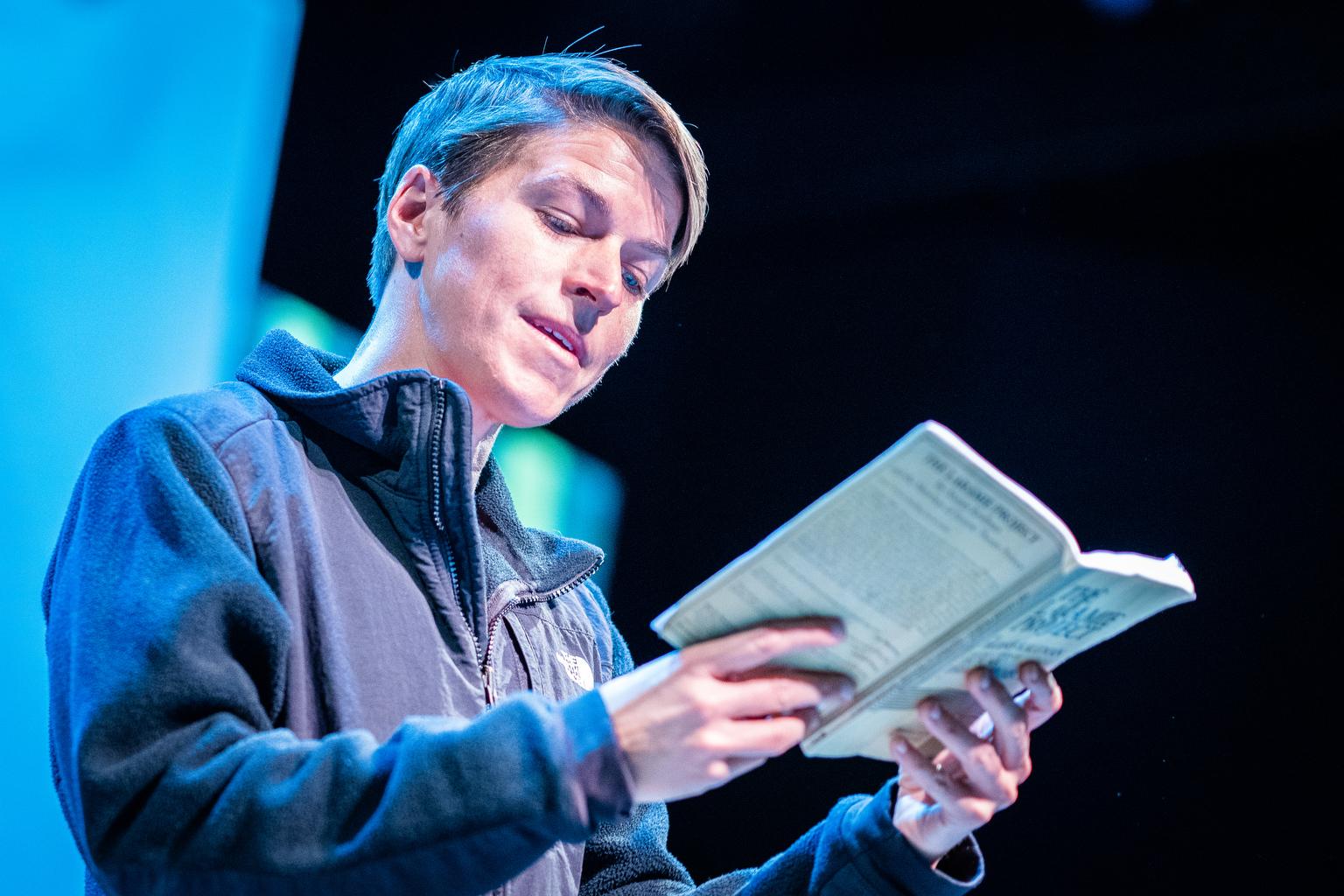

“The Laramie Project” uses interviews with hundreds of the city’s residents, intertwined with excerpts from media coverage and diary entries from the actors who originated the play, to create a ‘documentary theater’ portrait of a community grappling with the horrific crime.

When the play first came into the world — it originally debuted in February 2000 at the Ricketson Theatre in a partnership with the Denver Center Theatre Company — it sent a shockwave through many communities that had the chance to see it.

And even now, a quarter of a century after Shepard’s murder, “The Laramie Project” is a risky departure from the plays and musicals the Arvada Center Theatre is most known for, according to Rodney Lizcano, who co-directed the show with Kate Gleason.

“Unfortunately, we're commemorating the 25th anniversary of his death, and so those conversations of 'have we changed? Has the needle moved?'” said Lizcano. “Has it really? Yes, the gay community and the queer community, we've achieved towards marriage equality, but the hate towards those communities hasn't changed.”

Shepard was attacked by two men who tied him to a fence and left him to die on a cold Wyoming night. While his murderers were sentenced to life in prison, Wyoming law lacked any provision to charge them with a hate crime. His killing, and the dragging death of James Byrd Jr. in Texas, eventually galvanized federal hate crimes legislation.

“I think it would be great if it really was not timely,” said Judy Shepard about the play. After her son’s death, she and her husband Dennis started the Matthew Shepard Foundation to combat hate.

“However, there are hate crimes going against the LGBT community… They have risen more in the last few years than they had in the past decade. It's incredible. The amount of hate crimes against all marginalized communities have gone up. The hate's just been unleashed. They started rising in 2016.”

While Shepard’s story is one of violence against a young gay man, his mother says it could have easily unfolded against someone based on their race or religion. “It's exactly the same story. I hope someday it isn't relevant anymore, but today it's more relevant than ever, in my opinion.”

The cast for this production consists of eight actors — and four understudies, an increase in the usual number from pre-pandemic times for the Arvada Center — giving voice to dozens of different characters. The directors gave a lot of thought to who should fill those parts.

“It was very important to me early on in the process that our cast and our creatives were largely queer,” said Gleason. “It felt important to me in telling the story. It felt important to me in the times that we're living in. So having this amazingly inclusive and diverse group of artists has been incredible.”

Laramie Project was developed by Moisés Kaufman and the New York-based Tectonic Theater Project; he and other members went to Wyoming to conduct the interviews for it. For a time, it was one of the most produced plays in the country. But when Arvada Center announced its new staging, there were some in the Denver theater community who questioned bringing it back.

“I remember reading one person say that it's not relevant, that they should pick a different story, that this Laramie Project is no longer relevant,” said Steven J Burge, an understudy in the play. “And it punched me in the gut because it's very relevant. Last year there was the shooting at Club Q. Our people are still being killed, still the victims of hate crimes.”

This is a very personal play for Burge; when the murder happened, he was the same age as Shepard and had only recently come out to his family.

“My family was finding their way through love. There was always love for me, but they were finding their way through love to acceptance,” he said. “And when this happened, it sort of almost gave them confirmation that everything they worried about was valid: that I was going to be beat up, I was going to be murdered, I would get HIV. All of these terrible things associated with being gay happened.”

But twenty-five years is a long time, especially for younger generations who came of age in the decades after the crime. Recent MSU Denver graduate Chrys Duran is making their professional debut in this production.

“I had actually never heard of (The Laramie Project) before. So I looked up this one specifically and I knew immediately that it was something I wanted to be a part of," said Duran. "Because of the importance of it. I saw all the history of it and how much the story of Matthew Shepard impacted the world and it being… such a catalyst for queer activism or just something that started a conversation and that is something I love being a part of anyway.”

The challenge of stepping into the play’s many roles

As what’s known as a verbatim play, “The Laramie Project” calls on its actors to voice ideas that it can be difficult for them to be the conduit for. They each must take the stage in a wide range of roles, including some with strong homophobic views and beliefs.

Actor Anne Oberbroeckling said there was one monologue in particular that she struggled to memorize “just because I was resisting what she was saying.” It helped her to remember something Kaufman said about the play.

“He says that the play is not called the ‘Matthew Shepard Story.’ It's called ‘The Laramie Project’ because it's not just about Matthew. It's about this whole area where this happened, which could be any place,” said Oberbroeckling. “I grew up on a farm in Iowa, so I know… there's a variety of people that make up those towns. So her voice needs to be heard. And some of the things that she says — a lot of what she says — I don't agree with, but you all know as an actor, you have to embrace what she says and who she is and love her as much as you love… the characters that are supportive of what's going on.”

Oberbroeckling copied into her script a line from the performer Billy Porter’s memoir to help her with portraying some of the play’s openly homophobic characters: “My life is testimony to the power that art has to heal trauma.”

“Isn't that amazing? That's beautiful,” said Oberbroeckling. “He talks about acting as, get the ego out and it's the service. It's service… your service is leaning into your truth, your queerness, your authenticity.”

Duran faced similar struggles when it came to embodying a character who served prison time with one of Shepard's murderers. Even once they found their way into the performance, the role is still a challenge.

"That's the one where, every time I exit that character, I take off the jacket he wears. And I'm still kind of shaking a little from the anger he has, but when I take off the jacket, I'm like, 'let this be,'" said Duran.

Co-director Gleason hopes anyone thinking about coming to see “The Laramie Project” will understand this production is for everyone. “This story is really a story about community and it's moving, it's funny. It's an oral history. It speaks to everybody, I think. I don't think it just speaks to one demographic of people.”

As Lizcano, the play’s other director, said, the goal in restaging “The Laramie Project” now is not to treat it as a museum piece from an earlier era, but to continue the conversation about how society defines love, hate and compassion.

The play runs through November 5th at the Arvada Center.

Editor's Note: The Arvada Center is a financial supporter of CPR, but has no editorial influence.

- Ballroom scene is emerging in Colorado, and it’s a celebration of LGBTQ culture and its contributions to society

- Former Weld County librarian wins settlement after district fired her for promoting LGBTQ, anti-racism programs

- ‘The only reason for our existence is connection’: A new artist residency aims to support BIPOC and LGBTQ+ artists

- ‘Just Us’ documentary explores the lives of LGBTQ people