As the CEO of Alpen High Performance Products in Louisville, Brad Begin is happy to explain how windows in the United States have fallen behind what’s available in other parts of the world.

But he thinks it’s usually easier to let people feel the difference.

The company demonstrates the point with a pair of chest freezers in its showroom. One lid, built from a standard U.S. double-pane window, is chilly to the touch. The other, an Alpen quad-pane window modeled after European designs, is barely cooler than room temperature.

Besides working as a nifty sales display, the freezers illustrate a major factor driving climate-warming emissions. The federal government estimates about 30 percent of energy used to heat and cool buildings in the U.S. goes out the window, forcing power plants and furnaces to burn more fossil fuels. The loss also costs home and business owners around $40 billion a year, according to another federal study.

Those deficiencies are also why better windows offer big potential benefits as a pragmatic climate solution. A report released by the U.S. Department of Energy last year found high-performance windows alone could cut carbon emissions 2 percent by 2050 and be “instrumental” in helping meet President Biden’s climate goals.

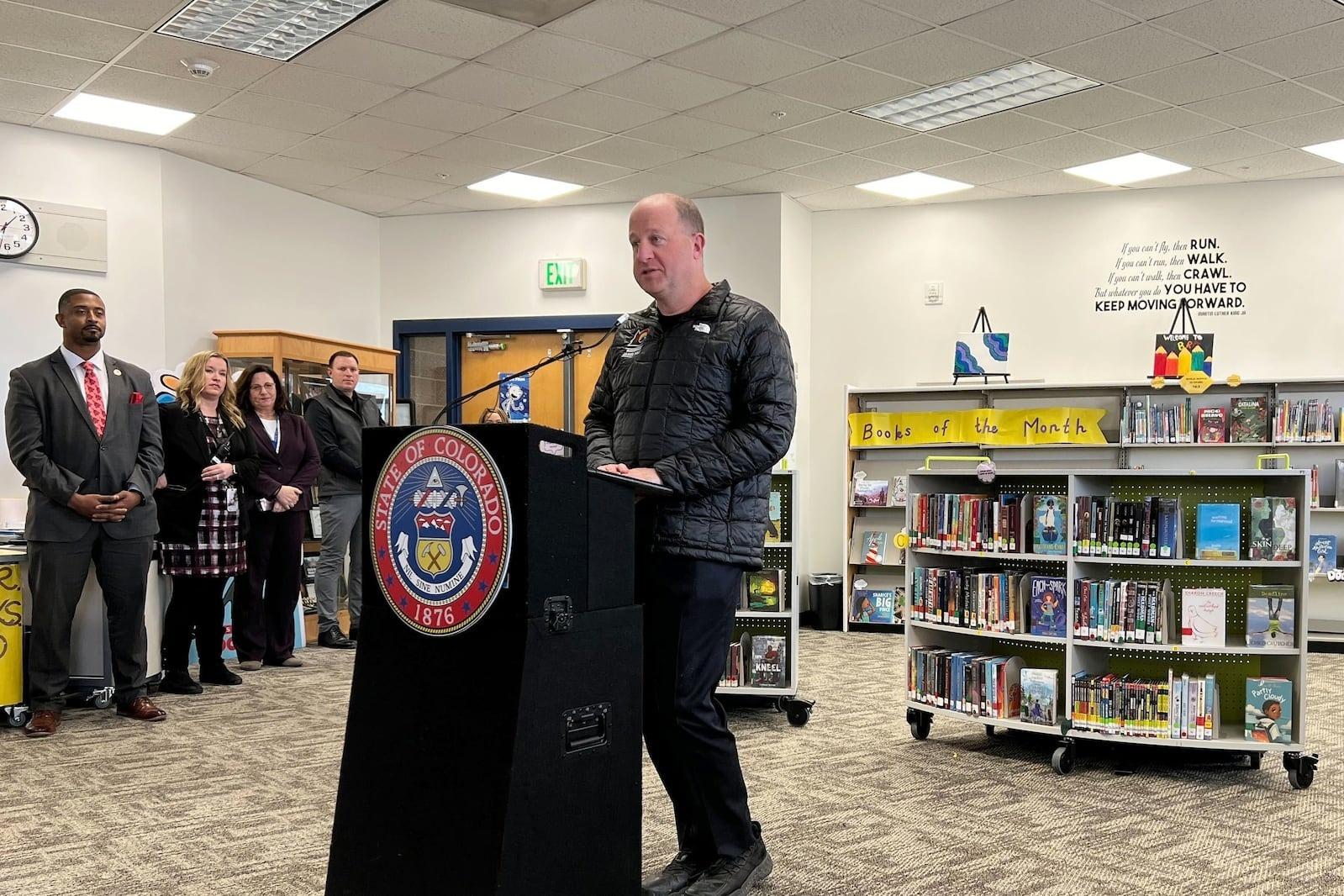

Alpen is now one of the companies working with the federal government to put the plan into action. It’s a tough task, but Begin is optimistic his industry is ready to commercialize recent innovations and meet a growing set of green building standards.

“The U.S. will catch and pass the rest of the world, but we have a pretty big hill to climb. We are way, way behind,” Begin said.

A clear answer from the past

To make progress, the U.S. will need to learn from decades of aggressive window improvements in Europe.

That progress kicked into high gear during the 1970s oil crisis. In Sweden, a set of strict building codes pushed developers to use triple-pane windows to seal homes and businesses against the frigid Nordic winters. Other nations soon followed suit, making thicker sandwiches of glass standard across the continent.

Meanwhile, the U.S. developed a tradition of thinner double-pane windows in narrow frames. The design accommodated a preference for hung and sliding windows, but it’s made manufacturers reluctant to add weight and heft to their products, Begin said.

Scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory patented a potential workaround in 1991 that used ultrathin glass to create a lighter triple-pane window packed with krypton gas. Tests showed it could slash air conditioning and heating costs, but the idea didn’t catch on due to the high upfront price.

Want more climate solutions from Colorado Public Radio? Sign up for our free climate e-mail newsletter.

Those economics shifted almost 30 years later. The rise of smartphones and flatscreen TVs made this glass far less expensive. In 2019, the same scientists asked Alpen to try to commercialize the idea.

“We started using thin glass three years ago, and it’s now in probably 90 percent of our products. We’ve had fantastic success with it,” Begin said.

Today, the factory floor at Alpen is like an industrial house of mirrors. Giant panes of glass reflect swarms of workers building frames and polishing surfaces. In the last four years, the company has tripled its workforce, filling orders for high-end homes, affordable housing projects and even the observation deck on the Empire State Building.

Begin credits a large part of the growth to states like Massachusetts, Minnesota, Washington and New York adopting green statewide building codes. Colorado is now joining the push with its own codes released last summer.

He expects upcoming Energy Star standards for doors and windows will further drive the market. Set to take effect later this month, the U.S. Department of Energy predicts the updated labeling program will lead to broad adoption of triple-pane window sales in cooler parts of the country.

It’s an exciting shift, but Begin thinks better-insulating windows are just the beginning of new innovations set to upturn the industry.

A window to the future

One idea already hitting the market is dimmable windows.

A set already offers a broad view of downtown Denver from offices at Golden's National Renewable Energy Laboratory, one of the government’s main incubators for ground-breaking climate tech.

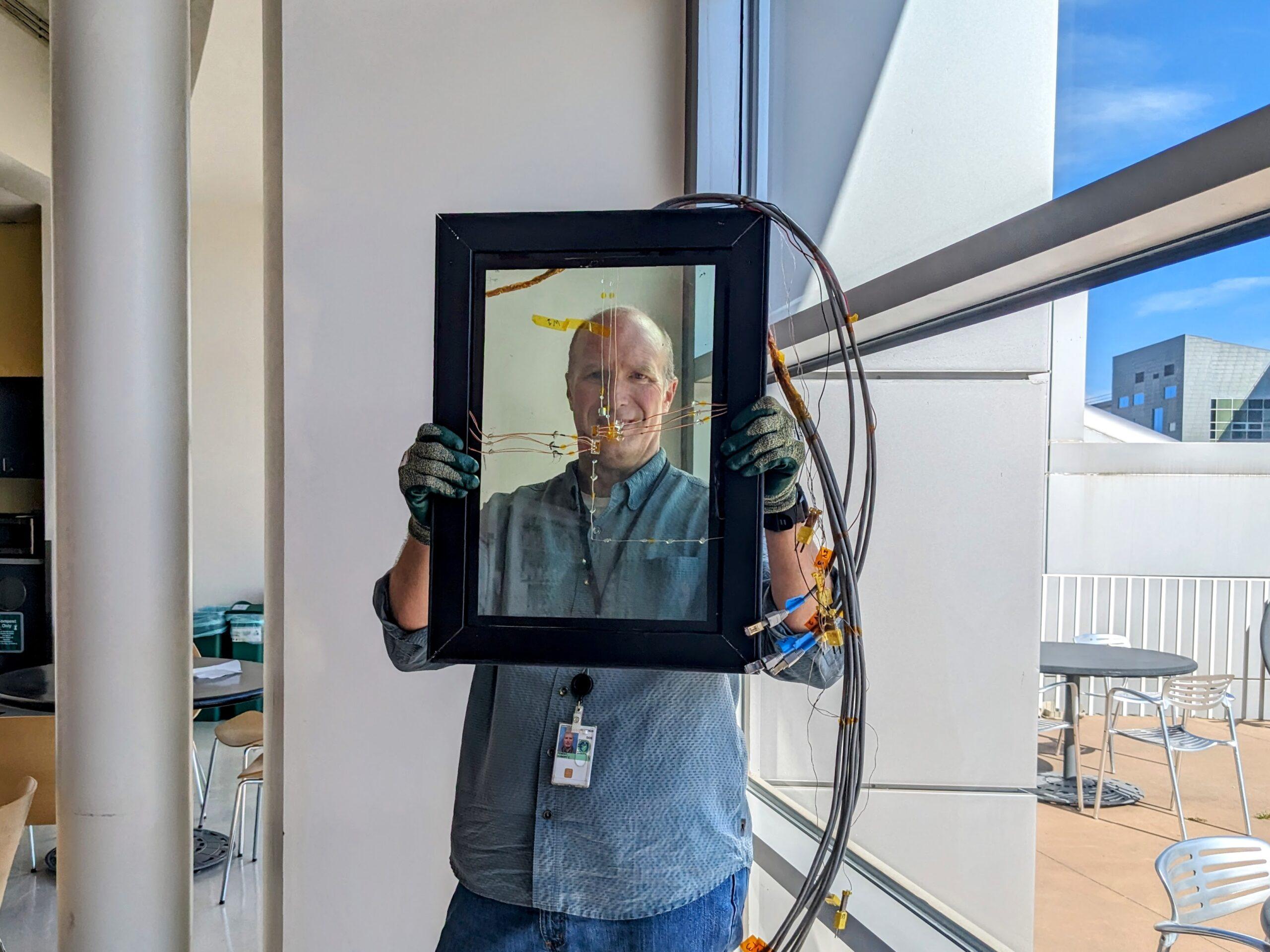

On a recent warm afternoon, NREL materials science researcher Rob Tenent pressed a button to slowly darken the windows, limiting the amount of light and heat entering the office. The process eases the burden on the building's cooling system. In the winter, it’s reversed to warm up the space.

Tenant and his colleagues are now working to add another layer: solar power. The team has pioneered the development of a window that darkens when exposed to sunlight and generates electricity.

Called SwitchGlaze, Tenant said the technology could someday change a basic assumption about windows. At the moment, he said architects still treat windows as necessary openings in a building’s skin, bleeding energy into the surrounding environment.

“By adding in the energy generation, we could create things that, if installed, could actually make it more energy efficient to put more glass in your structure,” Tenant said.

While it's a cool idea, NREL researcher Chioke Harris said many emerging technologies will be expensive in the short term. In his view, the real holy grail is window improvements accessible to everyone, not just “people who live in million-dollar homes in Aspen.”

One example could be a window insert manufactured by Alpen. The federal lab is now evaluating the experimental dimmable version of the product, which Harris said could soon give renters a way to cut their energy bills easily without demanding retrofits from landlords.

“You put those windows for the time you’re in the space. Your lease comes up, you vacate the space, you take them out,” Harris said.

A view of better homes

Until a wider market drives prices down, the early adopters of the next generation of U.S. windows are homeowners like Kevin Lombardo, an information technology manager at NREL.

His original house in Lousiville was one of more than a thousand lost to the 2021 Marshall fire, the most destructive blaze in Colorado history. In the aftermath, residents battled over the community’s strict green building codes before the city council carved out exceptions for fire victims. Lombardo’s family nevertheless resolved to rebuild the most climate-friendly dwelling possible.

“We just polled the family and determined it seems like we ought to do every single thing we possibly can,” Lombardo said. “This is our absolute best shot.”

The result is a home dubbed the Sunflower Sanctuary, named after the curvy suburban street that now hosts the boxy monolith of a house. Its hulking walls should help it earn a Passive House certification, widely considered the gold standard for energy-efficient homes. If construction stays on schedule, Lombardo should move in next February.

One of his favorite features is the broad, three-pane window in the corner of the living room. Made by Alpen, it's positioned to display the mountains and welcome the winter sun.

Lombardo said it’s even more gratifying to know it took decades of research to open up the view.