On a recent fall day at the Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library, Dexter Nelson II was considering how to update the technology in one museum, how to spread the word he’s looking for artists to show work in an on-site gallery, and how to help a colleague get learning materials to a school for Hispanic Heritage Month.

“So she’s like, ‘Where’s the Hispanic stuff?’ I’m like, ‘Nobody knows.’ She said she found some stuff. She’s like, ‘Well, how did I get this?’ So, now it’s a whole process of creating a process for this … It’s like building a plane while you’re up in the air,” said Nelson II, the library’s new Museum and Archives Supervisor.

Since starting the position in July, he manages and supervises a staff of four, all of whom focus on the museum, gallery, and archives on the second and third floors. He has a few immediate goals recently completed, and a few goals to fill. One completed goal is hiring a new Library Program Associate to create programming specific to the archival collection — which includes audio tapes of Colorado’s first Black surgeon, artwork of the first Black person in Colorado, and hundreds of vinyl records.

Goals ahead include updating the museum, gallery, and glass memorabilia cases, which haven’t been changed since 2003, when the library opened. He’s also planning to curate a revolving show in the gallery upstairs and spruce up the technology by replacing the VHS players that are there now.

“A lot of history has happened since this opened in 2003,” said Nelson II, who has a Master of Arts in Museum Studies from the University of Central Oklahoma. “We want to make sure we’re acknowledging that.”

His task of updating, managing, and curating the special collections library and archives on the second and third floors is separate from the operations of the branch library on the first floor, which reopened in August after a $2.8 million, 18-month renovation. Now, pictures from the archives are displayed on bookshelves; and a teen area, study rooms, bright couches and seating areas encourage people to hang out. The HVAC system was updated and the building made ADA-compliant as well.

Meanwhile, the second and third floors are getting not so much of a facelift but more of a blood transfusion, with Nelson coming aboard a few months ago. He previously did similar work at History Colorado as associate curator of Black History and Cultural Heritage, and he picks up where Terry Nelson (no relation) left in her similar role as a Special Collections librarian.

On his team are people deeply invested in the work of archiving, researching and preserving Black history in public spaces – including one with ten years on the job, the other new as of this fall.

Special Collections Librarian Archivist Annie Nelson (no relation to either Terry Nelson or Dexter Nelson II) had already spent a decade in her role as both archivist and librarian when Nelson II joined the team. “I primarily work behind the scenes and I prefer it that way,” she said in an email.

In her archivist role, she prepares and rehouses collections for researchers, helps them identify collection materials and provides guides describing the arrangement of boxes and folders in a collection. Her librarian role involves interacting with patrons by phone, in person and by email. She has helped build the non-circulating African American history and culture research collection for the second-floor archive and research reading rooms.

She said she feels enthusiastic about what Nelson II will bring: “I am looking forward to Dexter's long-term and short-term goals of bringing some fresh newness to [the third] floor museum. It is time for change that reflects African American stories in Colorado that enlighten [and] raise awareness that there is more about African American history and culture to be told. I think Dexter will be the key to creating that new venture and engagement.”

Joining Annie Nelson and Dexter Nelson II is someone whose last name isn’t Nelson. His name is Shanti Zaid, and he started in mid-September as a Library program associate, working specifically with the special collections and archives on the upper floors.

He relocated from Michigan to Denver during the pandemic after twenty years in academia and taught online for a while “until this job came up … this is kind of a dream job for me,” said Zaid, 43, who has a dual Ph.D. in African and African American Studies and Cultural Anthropology from Michigan State University. “Coming to a space where I can . . . apply it to a new history, a new area, a new community, has been just absolutely thrilling. It’s a brand new research project to dig into and get excited.”

The library has other program associates, but he said he is the first one assigned to the African American special collections and archives, he said. Since he started, he’s been working on enhancing the tours offered of the in-house museum by broadening what guides share with the public, but he said he’s not ready to give an exhaustive list of the different things he will be doing. “I’m also just exploring our special collections and archives and seeing what kinds of materials we have, seeing some of the figures and some of the events in there, and trying to do some more background research to understand those so I can develop some kind of robust programming around those figures and events.”

He has another idea he’s working on that involves the many boxes of vinyl records he discovered in the collection, much of which is in storage off-site while the temperature of the collections library can be calibrated to make it optimal to preserve the archival materials. “One of the events I’m trying to get off the ground pretty soon is a kind of ‘Vinyl Vibes Lunch Hour,’ to just play some old music, talk about the period, talk about some of the figures, some of the relationships, what was going on in Denver there, and let it be kind of a relaxing, just enjoyable vibe there.” He envisions people from Five Points getting into the habit of popping in once it becomes a regular thing.

He said some of the records he’s found are by Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong, but he has no idea what else he might come across. “I'm just getting started digging through there, trying to find maybe some local artists that we can have in the collection,” he said. “I haven’t found those yet, but I’m still holding out hope.”

Another plan he has is to collect oral histories of Black Coloradans, especially from “people that are elders that have been in the community for a long time that have dynamic stories to share,” he said, his voice filled with excitement. “We want to get those recorded and then we can figure out the rest.”

He has already come across a digitized version of an oral history from 1974 by the man believed to be Colorado’s first Black surgeon, Bernard F. Gipson, Sr., who recalled with joy serving as a doctor at Yankee Stadium during the World Series in the early part of his career when he practiced medicine in New York City. It is now a digitized multi-part recorded oral history people can listen to.

Zaid also said his experience in academia prepares him to help high school and college students with research assignments, tailoring training to each level. “We are in this unique position to have a public library, a research library and a museum, trying to really utilize our research library and museum space for the educational encounters of students.”

Nelson II also intends to add to the team an additional staffer who can update the exhibit spaces – something Zaid plans to get involved with as well.

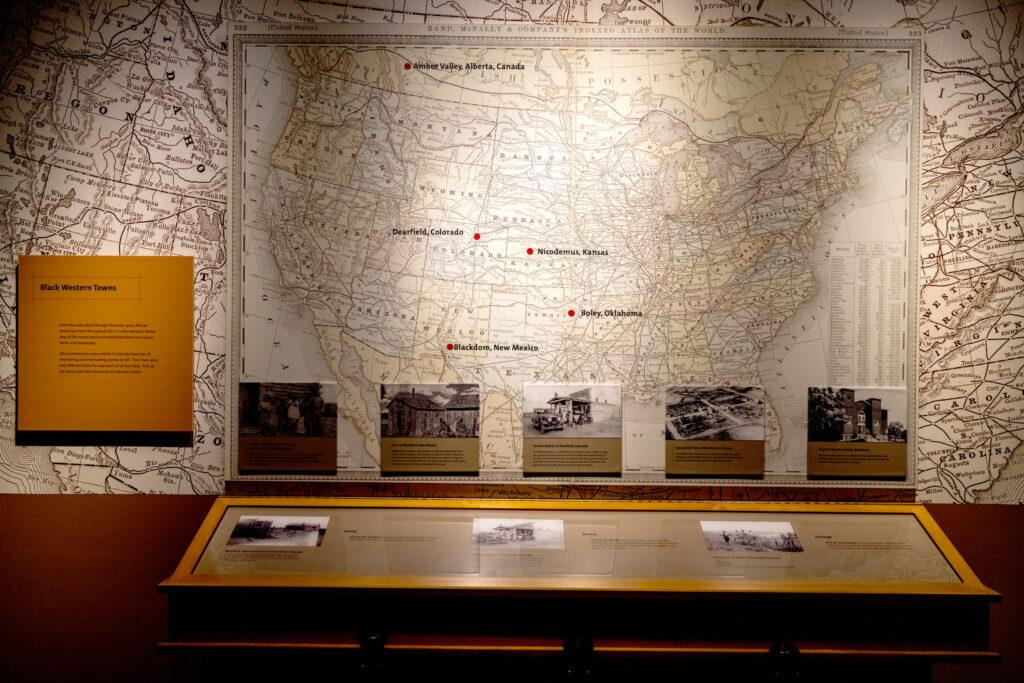

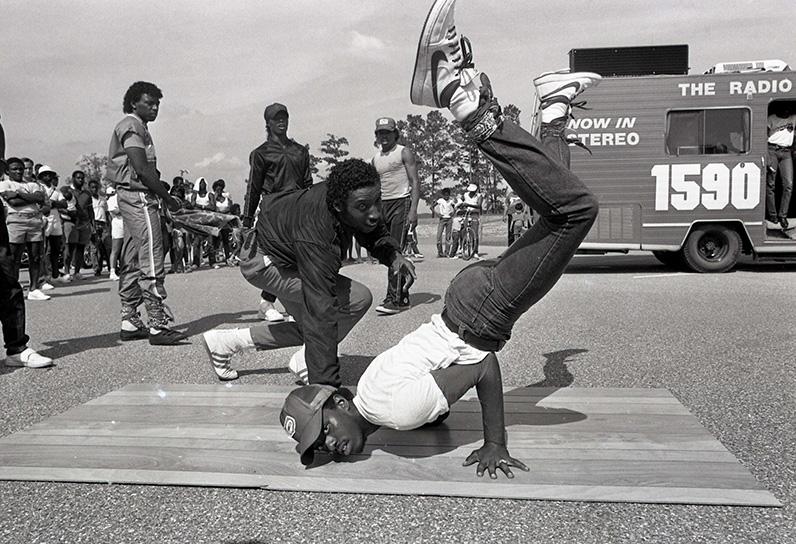

During a recent tour of the third floor, Nelson II pointed out some dated artwork in the Western Legacies Museum, a museum housed on the library’s third floor. “It was done in 2003, and has not been changed since,” he said, laughing with a touch of frustration. “It’s not discrediting anything that’s here; it’s just time for an update.”

He also pointed out a temporary exhibit in the Charles and Dorothy Cousins Gallery, which he plans to replace with a revolving exhibit by local artists. “We want this to be an active space where people know they can come in and expect to see some new art or an artist who they’re familiar with.”

On the same floor is a small theater where a class of students might watch a film; one of his other goals for that area is to find up-to-date technological equipment. “What’s the level of remodel?” he wondered aloud. “Is it just taking down graphics and putting up new skins of images, or are we moving some walls and some things like that?” Gesturing to clunky metal rectangles protruding from the ceiling, he said: “If it’s not a VHS player, it’s a DVD player or some system akin to it. And so what does it look like to remodel that? Is it something where we could change one unit, or do we need to completely remove it and then retool it because it’s so old?”

Another goal is to unite the first-floor branch library with the upper floors housing the museum, gallery and special collections. “Ideally, there should be content that people can consume on the third floor, and then you can read a book about it on the second floor, and then you could take a book home on the first floor … we really want to stretch content through all three floors.”

Four other African American research libraries

The work Nelson II, Nelson and Zaid are doing in Denver is similar to what other archivists, research librarians, programming associates and their supervisors are doing in the country’s four other African-American research libraries in Fort Lauderdale, Houston, New York and Atlanta.

In Ft. Lauderdale, for example, the African-American Research Library and Cultural Center, part of Broward County’s public library system, is 60,000 square feet large and houses both an auditorium and an exhibit area. Its collections include 3D models of African artifacts; a large collection of Haitian art; an Alex Haley collection with eight of his unfinished manuscripts; over one million “ephemera and manuscripts” in English, Kreyol and Portuguese – including posters, postcards, obituaries, stamps and sheet music. Later this month, it will have a sci-fi and comic convention.

In New York, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, part of the New York Public Library system, is featuring the exhibit, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, by artists who have and haven’t been incarcerated. Its collection focuses on the Americas, the Caribbean, and Sub-Saharan Africa, and its digital collection includes papers entitled “The Negro in Business;” “Nigeria: Its Peoples and Problems;” and “The Story of the Illinois Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs,” which dates back to 1900.

At Houston’s African American History Research Center, part of that city’s public library, people can record oral histories. Opened in 2009, it mainly archives materials about local Houston families, local politicians and community members.

“We're really getting back to those of community-, individual-, and organization-based oral histories, as well as trying to build partnerships with the community so that they are able to direct the oral histories that they want to capture,” said Sheena Wilson, assistant manager and lead archivist. They’re also working on digitizing 20,000 negatives of photojournalist Ben DeSoto, who shot pictures in the Houston area for 20 years.

In Atlanta, the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History opened in 1994 as part of the Fulton County Library System, specializing in reference and archival collections focusing on African and African-American culture and history. It reopened in 2016 after being closed for two years for a $20 million renovation.

What ties the African-American research libraries together are a few things: they are repositories for history that might otherwise be erased, and they create places where anyone can go to get information they might not know is there, according to Nichelle M. Hayes, president of Black Caucus American Library Association, a stand-alone organization that advocates for African-American librarians and library patrons.

“Things that are important to us, we study and preserve, and that’s something that a research library will do,” she said, adding that Black history in particular asks for a place to be preserved. “Especially when we’re talking about the African diaspora and those things have literally and figuratively been written out of history, so when you have something devoted to that, what you can do is focus locally, which is always really important to see where you fit into the story.”

Hayes added that research libraries are for everyone. “You don’t have to be a researcher or someone who’s writing a book to tap into those resources and to be able to enjoy them,” she said. “There might be something about your personal history, either your family or where you’ve grown up or where you live now, and information is really powerful.”