Colorado’s political landscape has shifted swiftly in just the past decade as the state moved from a purple presidential toss-up to a deep blue Democratic stronghold.

But that doesn’t mean Colorado doesn’t still have hundreds of thousands of conservative residents living all across it. And that had one of our listeners asking Colorado Wonders: What part of Colorado is now its reddest?

To answer that question requires first coming up with a definition for how to measure a place’s political character.

Colorado’s independent redistricting commissions recently had to do just that, in order to calculate the competitiveness — or lack thereof — in the districts they were drawing.

“Because of the increasing number of unaffiliated voters in Colorado, I think it's important to look not just at voter registration but at election results,” said Jeremiah Barry, an attorney with the state legislature who was among the staff that advised the commissions during their work in 2021.

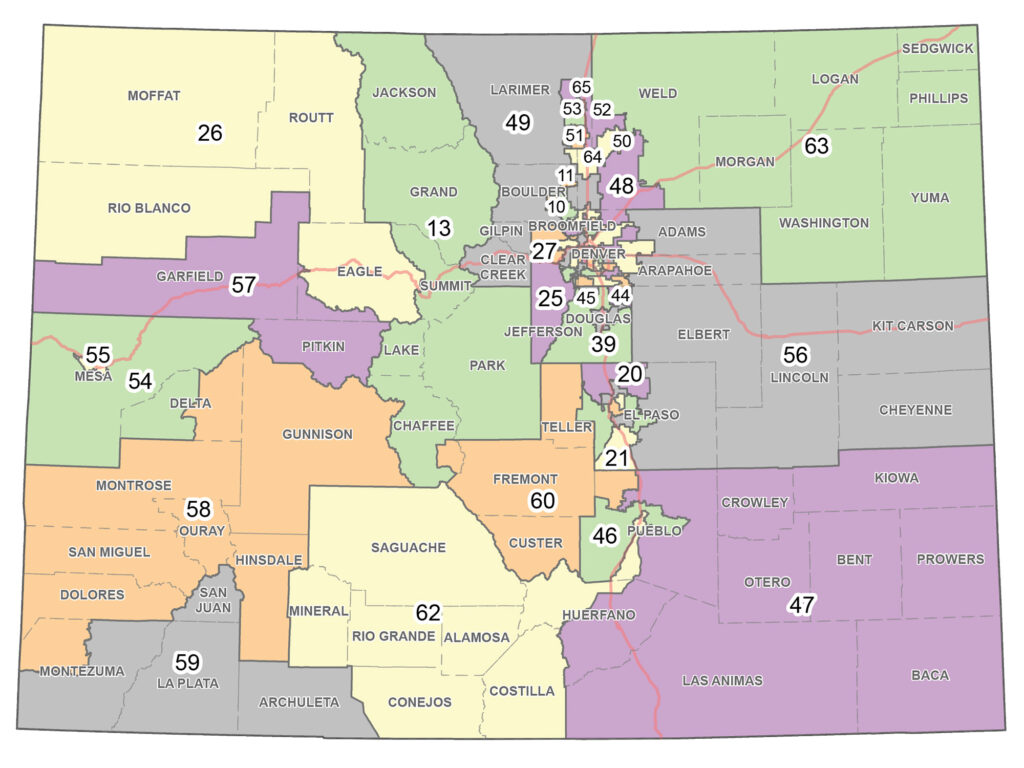

To determine each state legislative district’s politics, staff looked at how its residents voted in six separate statewide races from 2016 and 2018.“Not surprisingly, the two most conservative districts are the two House districts in northeastern Colorado,” said Barry.

A red corner in a blue state

Together, House Districts 63 and 56 cover a full corner of the state, from the Wyoming, Nebraska and Kansas borders down to the eastern half of El Paso County.

The area is sparsely populated, full of ranches and farms and small towns. And while Colorado does have many other rural districts, what makes these two different is that they draw very few voters from cities or suburbs. They also lack the kind of liberal resort towns that make mountain districts more politically mixed.

State Rep. Richard Holtorf represents one — HD-63 — at the capitol. When the legislature is not in session, he runs and manages his family’s ranch near the Washington County town of Akron.

Holtorf proudly tells visitors to Buffalo Springs Ranch that the earliest known record of it dates back to 1892. When he took me on a tour recently, he paused to check in with one of his employees, reminding him he had until sundown to move some bulls down four miles of trail.

“Mama, don’t let your babies grow up to be cowboys,” Holtorf sang jokingly, before concluding, “mama screwed up.”

At the statehouse, Holtorf has focused on agriculture issues, and regularly urges his Democratic colleagues to respect Colorado’s ongoing rural-urban divide.

“If you want to keep your city slicker policies in the big town, keep it. But don't bring your mess out here and mess with us,” is how he explained his views. “Let us live our lives and do the work that we want to do, that we love to do, and just stay out of our way.”

Holtorf is contemplating a job change with the potential to take him far from his ranch, though; he announced earlier this fall that he’s considering mounting a primary challenge to Republican congressman Ken Buck.

To get a better sense of the people behind the area’s politics, Holtorf suggested I talk to his neighbor John McCord, who lives a few miles away along a dirt road.

McCord’s house is more than hundred years old and sits in a big yard where chickens, geese and ducks wander, along with his dogs. Several large truck beds sit in a field nearby, along with other trinkets and metal scraps.

“I've never lived in town. I hate towns. I was born and raised in a junkyard, which you could kind of tell,” explained McCord dryly.

McCord is a retired truck driver. He lives with his wife and adult daughter who has cerebral palsy. He follows politics closely and said he’s glad this area is very conservative.

“I'm always willing to listen to the other side and bring up points why I'm like I am. And I'll listen to their side. I don't get mad.”

He’s pro-Second Amendment, pro-Trump, and pro-border security. He believes all of the legal challenges against Trump are wrong, and that President Joe Biden shouldn’t be president.

"He's as corrupt a politician as ever lived. But I'm not naive to think that there ain't Republicans just as crooked. I think probably over half the Republicans and probably 60 to 75 percent of the Democrats are crooked, more crookeder than a barrel of guts, as my grandfather would say.”

Despite having no desire to live in town — the nearest one has a population of less than 2,000 — McCord loves his community but not how divided the country has become.

"There's people who literally hate and (are) ready to punch a Democrat. And Democrats who are the same way. You can't live like that,” he said. “We're all Americans and we should try to come to some common ground. I really believe if things don't change, we're going to have a civil war or a national divorce. I would be for a peaceful divorce.”

One in five Americans would support a national divorce — a bloodless severing of red and blue states into their own countries — according to a poll earlier this year by Axios and Ipsos. However, this very red part of Colorado shows exactly why it would be such a hard concept to execute; nearly every state is made up of left leaning cities surrounded by conservative rural areas. The fissures are as much within states as they are between them.

That tension fueled a secession movement here a decade ago. There was an organized effort to break off from Colorado and form a new 51st state, but it failed in the early stages. In recent years, while the character of the area hasn’t changed, residents say more people from urban areas have been moving to the region.

“They just like the quietness out here. There's not so much hustle and bustle,” said 20-year-old Josie Nielsen. She works at the Books on Main store and cafe in downtown Fort Morgan. The town an hour east of Greeley is one of the largest in the area with around 11,000 residents.

Nielsen noted Fort Morgan’s tourism boomed last summer after it was featured in the HGTV series "Hometown Takeover," which remodels and updates parts of the selected community’s downtown. Neilsen says the show led to more community partnerships and projects and drew people even closer.

“Everyone has that sense of pride with their ranches and stuff. Everyone works together and wants to help,” she explained.

Her colleague, 16-year-old Adalee Bridges, says she doesn’t follow politics much but that the high school kids in Fort Morgan tend to lean more to the left than their parents. She’s enjoyed growing up in Fort Morgan.

“I feel like most people get it right with what they think of Eastern Colorado. It's really flat (and) windy, but it's not as bad as people think it is.”

It’s also more diverse than some might expect; ranches, farms and the large meatpacking plant in Fort Morgan have drawn thousands of immigrants and refugees to the area. The majority of Morgan County residents are not white and nearly a quarter of households speak a language other than English at home, according to the 2020 census.

Bridges likes the small-town feel here, and said her friends in larger cities comment how there’s always a lot going on in Fort Morgan compared to where they live.

“They say, like, ‘Wow, it's so weird. Your town is always doing something and they support small businesses so well.'”

A few doors down from the bookstore, I met Republican county commissioner Gordon Westhoff over tacos at a popular Mexican restaurant called Acapulco Bay. He described his priority in office as preserving local autonomy and the way of life here, which he says hasn’t changed much since he was born.

As for this being the reddest part of Colorado, he’s not surprised at all, but notes that politics aren’t the biggest driver here.

“A lot of people just don't really care and they're tired of hearing about it. And then some people are really concerned about it. The country's going downhill is what they call it. Or going to the trash can. Different other adjectives too… But we're all trying to get along.”

Still, Westhoff said Colorado’s increasing shift to the left has his wife pushing to move away, to a conservative state. Westhoff isn’t ready for that yet. He says the red parts of Colorado still have some fight left in them, and holds out hope that maybe the rest of the state could swing back in their direction before too long.