A sweeping proposal to overhaul the state’s tax system was decisively rejected by Colorado voters in Tuesday’s election, with backers of Proposition HH conceding defeat just an hour after polls closed.

Prop. HH combined several Democratic priorities in one long proposal. It was widely advertised as a way to cut property taxes, but it also came with significant changes to how the state collects, spends and refunds general tax money for years to come.

“It just says to me that this wasn't good enough and that legislators need to get to work. I think we need to build a coalition, and that's going to be hard work,” said Scott Wasserman, a progressive supporter of the measure.

Its defeat is a double blow to Gov. Jared Polis and fellow Democrats. First, it leaves them without an answer to next year’s property tax increases, despite saying for months that they would take action. Because of increases in property values, tax bills are set to increase by 30 percent or more for many home and business owners.

Republicans have pressed Polis to call a special legislative session so that lawmakers can enact property tax relief before the new year, but he has made no such promise. Conservatives also are advancing their own ballot measure next year.

The results also mean that Democratic efforts to loosen the fiscal limits of TABOR have been defeated once again. They have tried to achieve a broad-based increase to general tax spending for decades but have seen only small successes.

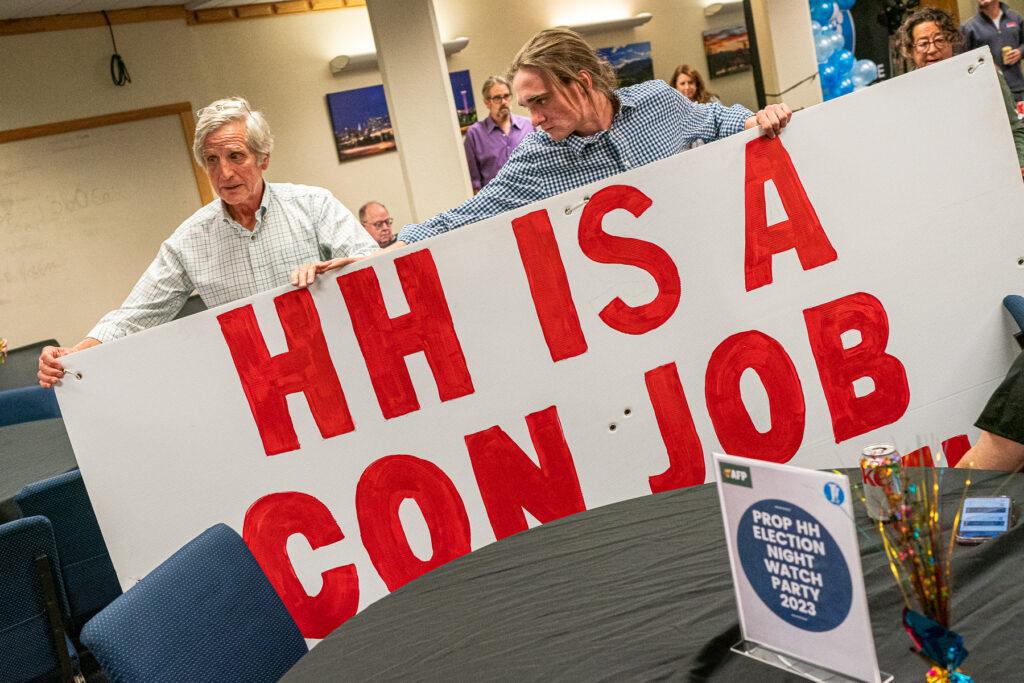

In defeat, the Prop. HH campaign blamed “far right misinformation” for their loss, which ranked among the worst results for a tax measure in recent years.

“Prop. HH was a nuanced, balanced policy that appears to have fallen prey to a misinformation slogan campaign by the far right, who would prefer to cut property taxes on the backs of our schools and fire districts,” said Senate President Steve Fenberg in a written statement.

But many voters said the problem was with the measure itself, complaining that it was too confusing or too complex. Prop. HH was one of the most complicated questions to face Colorado voters in years, requiring a dozen pages of explanation in the state’s official voter guide.

Some of the measure’s supporters acknowledged that the on-air messaging failed to portray the full scope of the measure — focusing on property taxes while downplaying the fact that it could divert billions of dollars from TABOR refunds to public education in the long run.

“I think that it has kind of a strange balance of different factors,” said Rep. Chris deGruy Kennedy, a Democrat who sponsored the measure in the legislature. “It's been difficult for us to explain that the way we constructed it is designed to not only hold schools harmless, but ultimately increase our ability to fund our K-12 schools.”

Or, as Wasserman put it: “This is a complicated issue… I think it tried to swallow the whole fish. It tried to solve our whole fiscal problem.”

The result: Voters had a wide range of contradictory opinions on the measure.

Some liked the property tax element. “I’m getting older, and I’m a homeowner,” said Mike Pearson, 54, a Republican voter from Arvada. His research had been limited to reading the ballot language, which emphasized the property tax benefits.

Other voters heard and liked the message of TABOR reform.

“I think we have taxes for a reason,” said Dan Moore, a 62-year-old unaffiliated voter. . “As long as they’re spent wisely, I don’t mind paying my taxes — I think TABOR has limited our ability to use some of the extra money as we’ve grown so much. ... I think this would be fine.”

But many others felt that something was amiss — whether they were concerned about losing a refund or simply skeptical of the measure’s complexity.

“It’s really a farce, the way it’s worded,” said Linda Groomer, 70, an unaffiliated voter who was unimpressed with the property tax savings.

In Aurora, at the election night party for incumbent mayoral candidate Mike Coffman, opponents of Prop. HH celebrated its downfall.

"It's a big night for our Taxpayer's Bill of Rights," Michael Fields, head of the opposition campaign, announced to cheers. "That ballot language was misleading. It had lies in it ... Voters saw straight through it, they didn't buy it at all. This is going down by a huge, huge margin."

Fighting on two fronts

The campaigns for and against the measure have each spent more than $2 million to sway voters. Much of its support came from education reformers, while its opposition came from the state’s broader conservative movement — with much of the money on both sides funneled through “dark money” organizations that don’t disclose their donors.

Education advocacy groups mobilized to support the measure, saying that it could deliver billions of dollars in new K-12 funding due to the TABOR changes. But that message didn't reach some potential supporters due to the campaign’s overall focus on property taxes.

Opposition from local governments added to the effort’s headwinds, with the groups representing both cities and counties officially opposed. Municipal leaders resented the way that Prop. HH imposed statewide changes to property taxes, which are primary revenue sources for local governments

It was difficult to overcome the combined opposition of conservatives and local governments, Wasserman said. Voters were simultaneously hearing messages that the measure would take away their tax refunds and that it could harm their local governments.

Meanwhile, the measure offered little direct benefit for people who don’t own property — leading to divisions even within the Democratic party.

What HH would have done

The passage of Prop. HH would have slowed a rise of property tax bills that's been driven by increasing property values and eventually would have offered a yearly discount of more than $1 billion for property tax owners, compared to the status quo.

At the same time, the measure would have reduced future TABOR refunds by changing the state’s spending limits. Over time, it would have allowed the state to retain hundreds of millions and then billions of dollars more tax revenue instead of refunding it to voters.

The refund money was to be used, in part, to balance out the effects of the property tax cuts — replacing some of the money that schools and local governments would sacrifice if property tax rates were lowered.

But it would also have gone further. Within a decade, the state could have retained up to $2.2 billion extra per year, with most of that money serving as a new source of revenue for public education.

Voters in Colorado have proved highly skeptical of measures that increase the general tax burden or alter TABOR’s core limits, although they have agreed to increase “sin taxes” and to pass a couple of more narrowly targeted tax increases recently.