Jackie Norris was just out of college when she found herself 8,000 miles away from home, talking to a GI at a rec center in Vietnam.

“I was used to patting people when I talked,” she recalls. “So I reached out and patted him on the arm and he went ‘Don’t touch me.’”

“I said, ‘Oh, I’m so sorry.’ He said ‘I just don’t think I can take being touched by an American woman right now.’ It was so poignant. It was why we were there but it was totally understandable. He was just happy to sit there and talk for a little while.”

Norris, who lives in Denver, was a Red Cross volunteer in the 1960s — one of 627 women who served year-long stints as “Donut Dollies” during the Vietnam War to bring a touch of home to servicemen laboring on the battlefield during a grueling and unpopular conflict.

The dollies inherited their nickname from their predecessors, young women who drove trucks in Europe in World War II, serving coffee and donuts to the troops.

Teri Hermans, who now lives in Aurora, got to Vietnam about a year after Norris left. She spent a lot of her time in Huey helicopters, traveling to several remote bases in a day.

“We would gather the guys together and maybe have (paper) airplane flying contests or just crazy stuff where we'd ask them questions,” she said. “They would compete against each other. They would get very involved in something that was totally distant from what they were used to doing.”

Norris and Hermans were in search of adventure when they were recruited out of college and sent to the war zone. Norris’ mother was a World War II dolly and her aunt served in Korea.

She initially signed up for the Peace Corps but her mother persuaded her to go to Vietnam, where she served from mid-1967 to 1968.

Hermans traveled the world as a child while her father served in the military. He was in the country at the same time she was.

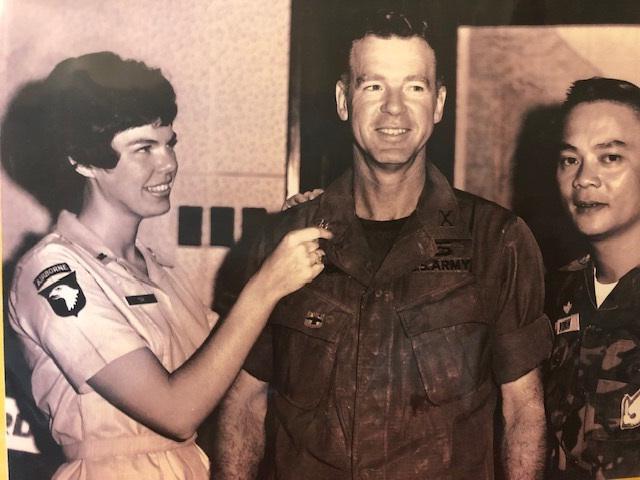

“I pinned on his colonel’s wings in Da Nang,” she recalled.

Both women said they felt well-protected in Vietnam, where they lived on bases far from the frontlines. They moved to different posts every few months because the higher-ups didn’t want them to become too attached to the troops.

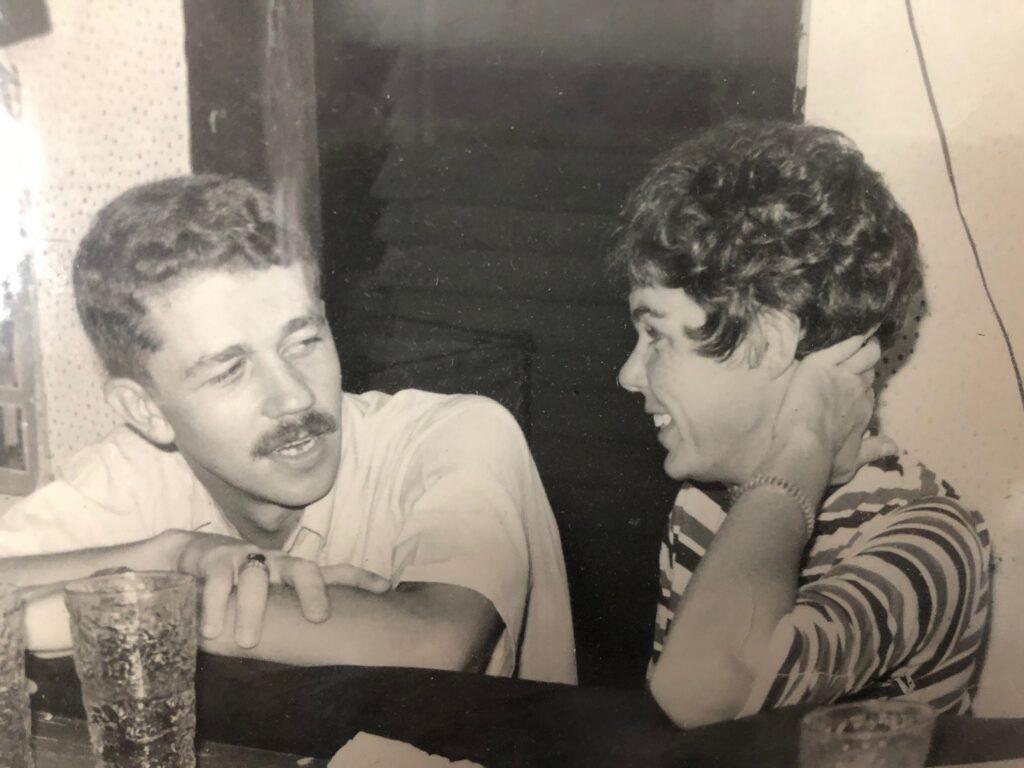

That didn’t entirely work out for Hermans, who met her husband, finance officer Jerry Hermans, at a makeshift officers’ speakeasy called the Barf Bar, although the relationship didn’t turn romantic until they were both home.

Both the women credited their wartime experience with boosting their confidence and preparing them for careers — but things were tough when they returned home to a country deeply divided by the war.

When Norris went to the University of Wisconsin-Madison to recruit for the Red Cross, campus officials didn’t publicize her speech because they were afraid she would draw an angry crowd. She later met her husband at an anti-war protest.

Teri Hermans said she and her father ultimately agreed U.S. involvement in Vietnam was a mistake.

“He and I talked about the war, and he agreed that it was a worthless war, but we didn't do any protesting or anything. He was still in the Army.”

Hermans said she and her husband seldom talked publicly about their experiences until attitudes toward veterans changed decades later.

Today, there’s a move in Congress to award the Donut Dollies the prestigious Congressional Gold Medal. Hermans doesn’t think that’s necessary.

“I have such mixed emotions because I don't believe that we did anything that extraordinary, so I don't know if it's something I deserve,” she said.

Norris agreed.

“We were so naive, we didn't know to be scared. And people have talked to us over the years about how brave we were. And my thought has always been, I hate to say this, but it was one of the best years of my life, just in terms of the experience.”