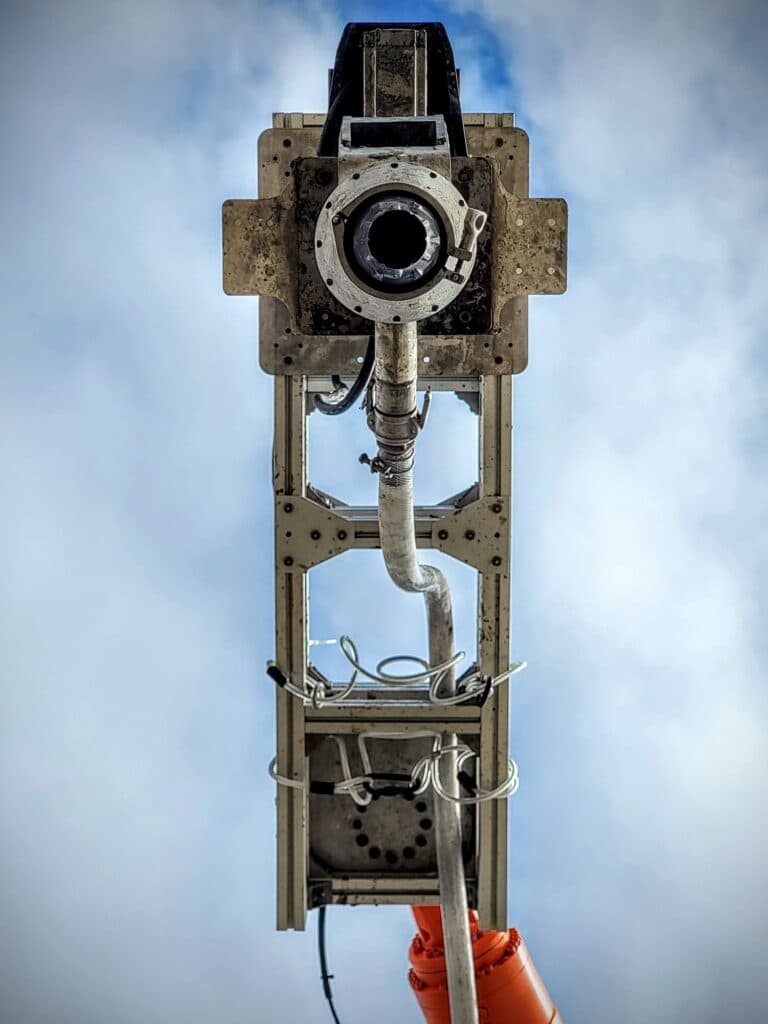

A set of nozzles squirt wet cement, swinging back and forth in a long line, squeezing out layer after layer. The result, at first, might look like some sort of cake — like icing at a bakery. Except, we aren’t at a bakery, we are on a construction site. And the nozzles aren’t held by a baker, but are attached to industrial-sized metallic cranes. The end result is something both common and futuristic, the foundation for a house — a 3D printed house.

While, to some, 3D printing might still sound like an obscure hobby, many are beginning to see the technology as a potential boost to the construction industry and a solution for the nation’s housing shortage.

“I had followed this technology for some time,” Cheri Witt-Brown, CEO for Greeley-Weld Habitat for Humanity, said. “For the first few years it was a little bit more expensive, clumsy, maybe not cost effective enough for affordable housing, but certainly a viable construction technology.”

The finished houses looked pretty much like any other single family home. Stone and white-painted wood pillars held up the front porch and traditional roof. Large windows sat on either side of a black front door. The only noticeable difference was a corduroy texture on the white exterior walls, due to the layers of printed cement.

It was during a visit on behalf of Habitat for Humanity to an Alquist 3D project Virginia — Alquist is the company that built the first owner-occupied 3D-printed home in the U.S. — that Witt-Brown became a believer.

“I've been in this business for over 37 years, and it's the first thing that's come along that will revolutionize the industry,” she said.

The homes went up faster, were more energy efficient and were easier to maintain. And the walls proved to be more resistant to natural disasters, like wildfires, an important benefit for Colorado.

And right now, 3D-printed buildings cost roughly the same as lumber-built homes, according to Alquist. They said as the technology improves, supply lines solidify and the scale of projects increases, the overall price of their homes should drop 20 to 30-percent.

“That's where we're heading. We're not there yet today, but within the next 24 months, we believe we will be,” Alquist Founder and Chairman Zachary Mannheimer said.

Mannheimer and much of the Alquist staff are in the process of moving their headquarters to Greeley, Colorado, as part of the company's national expansion.

“Solving our housing crisis is all hands on deck,” Gov. Jared Polis said in the press release welcoming the company to the Front Range. “Innovative solutions like Alquist 3D and communities like Greeley are crucial to our success in lowering construction costs for housing and infrastructure.”

Alquist had been in discussions with six different states. Mannheimer said incentives and agreements made Colorado the best fit.

“Greeley has all the pieces in a recipe for how [the industry] could actually grow organically,” Mannheimer said.

The tax credits and other incentives offered by the state and the city total more than $4 million. In exchange, the company expects to eventually create about 79 new jobs, with an average annual wage of $73,987, based out of a new showroom and production facility.

Mannheimer said its new Colorado home will be the only place where 3D concrete printing robots are designed, built and used to build homes alongside a purpose-built workforce development program.

“We're viewing this, Greeley, as the epicenter of the 3D printing movement,” he said.

Alquist’s expansion is part of a budding industry, as startups race to prove their technology is faster, greener, safer and cheaper than traditional residential construction.

In Colorado Springs, a 3D home printing startup named StructureBot works out of CEO Jim Scott’s garage.

“We're building large-scale, 3D construction printers,” Scott said.

Scott’s whole garage is filled with a functioning prototype: a 16x16 foot gantry system all supporting the robotic movements of a simple enough looking nozzle. It’s the programming which guides that nozzle and the concrete mixture that comes out of it that could change the game.

“We can use any number of other chemistries to do the same kind of work,” said StructureBot Chief Innovation Officer, Cameron McRoberts.

He listed examples like additives that would make the final walls stronger, or materials like red clays found in Colorado that would make the cement workable at lower temperatures.

The team’s current 16x16 foot design only builds walls enclosing about 300 square feet, appropriate for projects like bus shelters or tiny homes. The company currently has a small grant from the Colorado Office of Economic Development and International trade.

But, Scott said, they are busy designing a 40-foot-wide version of their system that can run much larger projects.

Similarly, Alquist will begin a partnership with the city of Greeley, likely before the end of the year, printing curbs and other infrastructure.

Alquist is also teaming up with Aims Community College to create a program that will train students on how to use and manufacture Alquist printing robots. The college claims the program will be a first of its kind.

“You could literally say the book hasn't been written,” said John Mangin, Aims Construction and Engineering Technology Department Chair.

3D printing education already exists at Aims Community College; it’s been part of its computer aided drafting program for years. That program has largely focused on the skills necessary for tasks like making small plastic models of objects designed on a screen — what most people still imagine when they think of ‘3D printing.’

But the new certificate in 3D concrete printing for homebuilding will sit within the construction management department. The program anticipates its first graduates by mid-2024.

“It’s a different wall system, but it’s still a residential construction project when it comes down to what we’re actually doing,” said Mangin. “You’re still going to have—obviously—plumbing, electrical and mechanical, that kind of stuff. So, that will likely be where students start.”

3D concrete printing robots can only build walls, currently. And, while those walls can be just about any shape, incorporating curves just as easily as straight lines and right angles, the technology as it exists now cannot build trusses or roofs. And, with notable exceptions, the robots can only build one-story tall structures.

Mangin said even students who graduate directly into jobs with Alquist will need an understanding of the rest of the homebuilding process.

“In a lot of ways, this new technology is really sliding right into a lot of what we're already doing,” Mangin said. “Except for that real specific portion about the 3D concrete printing, which is brand new.”

Meanwhile, Greeley-Weld Habitat has begun a small partnership with Alquist. They expect to build between five and ten houses at its 174-home Hope Springs development.

“We will actually ‘office’ in the first home,” Witt-Brown said, “So that we can live in it, we can see how it feels, we can experience, ‘What does it feel like to spend eight hours in the 3D-printed home?’”

If those initial homes turn out as well as she hopes, she could see her organization approving 50 Alquist homes in 2025 and more beyond that.

“[It’s] something that I already feel like I can see the outcomes,” she said. “But we have to prove that.”