Colorado’s struggle to decarbonize its transportation system has it set to miss its first legally mandated climate targets.

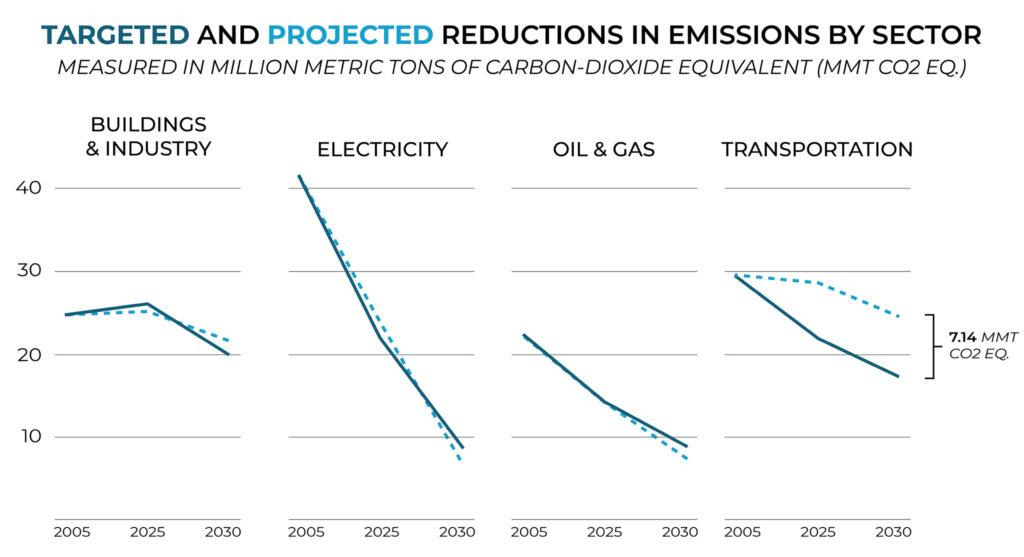

The state is making significant progress in reducing greenhouse gas emissions by shifting away from coal-fired power plants toward wind and solar power. Oil and gas regulations are also expected to help push down Colorado’s contribution to global warming.

But a new state analysis released this month shows that without aggressive new policies, the state will likely miss its first two sets of greenhouse gas-reduction goals — set for 2025 and 2030 — due to slow progress cleaning up emissions from the transportation sector, a persistent challenge chiefly because of the state’s long embrace of automobiles.

Light-duty vehicles like passenger cars and pickups account for more than half of the state’s transportation-related CO2 emissions, with the rest coming from heavier vehicles and aircraft.

Top state officials admit the state will almost certainly miss its 2025 climate target. First established by an ambitious law in 2019, Gov. Jared Polis claimed the plan would kickstart a “holistic approach” to clean up Colorado’s economy. His administration has since repeatedly clashed with environmental groups over regulations and additional legislation meant to enforce the targets.

State law requires Colorado to cut its emissions 26 percent below 2005 levels by 2025, 50 percent by 2030, and 100 percent by 2050. The state-commissioned analysis from environmental think-tank RMI shows current policies will get the state 79 percent of the way to the 2025 target and 84 percent to the 2030 target.

It’s also clear transportation is driving the shortfalls.

Major sectors like buildings, industry, oil and gas, and electricity generation are set to meet or approach the first set of goals. But the new modeling shows the state is only set to achieve nine percent of its 2025 goal for the transportation sector and 41 percent of its 2030 target.

Transportation is the largest single source of emissions in the United States and Colorado. To avoid the worst consequences of climate change, the federal government and United Nations scientists agree that the sector’s carbon footprint needs to nearly disappear by 2050. That task has proved “incredibly more complex” than closing a few coal power plants, said Will Toor, executive director of the Colorado Energy Office.

“You literally have millions of individuals making decisions about how they're going to get around, what vehicles they're going to use,” Toor said in an interview.

So far, the state’s transportation climate strategy has included new rules and incentives designed to sway Coloradans away from gasoline- and diesel-burning vehicles and toward cleaner electric vehicles. Transportation officials have also dropped some planned highway expansions.

And while those efforts are pushing the state in a cleaner direction, officials within Polis’ administration acknowledge new policies — like land use reform and more public transit funding — are necessary to bring later targets into reach.

Such changes could transform how many Coloradans live and move in their state.

Whether in historic mining towns like Leadville or big cities like Denver, Colorado’s oldest neighborhoods feature businesses and homes packed tightly together. Residents used their feet, streetcars, or intercity passenger rail lines to get around in the years before the automobile.

That all changed starting early in the 20th century. Cars made the state’s mountains far more accessible, and they reshaped cities too. Sprawling single-family neighborhoods became the law in most of Denver by the 1920s. Streetcar lines and passenger rail networks went defunct in the ensuing decades as governments built highways and mandated large parking lots. Such government subsidies pushed growth out into the suburbs.

Colorado is now firmly an automobile-dependent state. The average Coloradan drove 9,284 miles in 2021, according to federal data. That’s close to the national average, far less than rural states like Wyoming, and far more than more urban East Coast states.

But Toor said two climate-related strategies could chip away at that car-dominant standard. They will also require lawmakers’ approval, which could prove difficult.

The first is an expected resurrection of Polis’ failed attempt to pass a state law mandating more residential density in the state’s cities and towns. If done correctly, Toor said, such reforms could make communities more conducive to walking, biking, and public transportation — reducing the need to drive in the first place. Research shows household emissions are generally lower in denser neighborhoods.

“The single, most important thing that we can do now on the transportation front really involves moving forward on the governor's land use agenda to make it easier to provide housing in our cities,” Toor said.

The other key piece, Toor said, will be expanding public transportation services across the state. Polis has historically resisted giving more state money to Colorado’s largest public transit provider, the Regional Transportation District, but key legislative Democrats are now preparing a bill to do just that.

Polis is also pushing for a vote next year to fund a new passenger rail line along the Front Range to connect the state’s largest cities, including Pueblo, Colorado Springs, and Denver.

The legislature will take up land use issues and the transit funding bill during its next session, which starts in January. And this time, said state Rep. Meg Froelich, D-Cherry Hills Village, Democrats will draft smaller land-use bills rather than one mega bill as they unsuccessfully tried passing last session, “so that the chunks are easier to chew.”

The state should also consider beefing up some of its existing transportation-climate policies, advocates say.

Environmental groups across the country lauded the Colorado Department of Transportation for adopting a climate-minded rule in 2021 that led to the abandonment of several planned highway expansions and the acceleration of some bus rapid transit projects.

However, some environmental groups and progressive legislators now say the rule needs to be used more aggressively, pointing out that CDOT still has expansion plans for Interstate 70 at Floyd Hill, Interstate 270 in Commerce City, and other congested highways.

Such projects are not compatible with a climate-friendly future and “do nothing but induce further demand and increase safety risks and increase [vehicle miles traveled] and emissions on our roads,” said state Rep. Ruby Dickson, D-Arapahoe County.

Other states have improved upon Colorado’s work, Dickson said. Where CDOT’s rule requires it and other planning agencies to estimate and limit the greenhouse gas emissions from their projects, Minnesota adopted a version that sets an explicit 14 percent reduction target in vehicle miles traveled per capita by 2040.

Governments can manipulate models to make highway expansion projects appear to be climate-friendly, said Matt Frommer, senior transportation associate for the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project.

“If the clear target is VMT reduction, you're not going to get those sorts of solutions that make driving easier and quicker,” Frommer said. “The focus will really be on expanding transportation options to things like transit, biking, and walking — if anything, reducing total driving.”

Frommer also wants CDOT to be responsible for eliminating more emissions with its rules than the state has already tasked it with. But there’s no consensus, even among climate-minded legislators, that CDOT should tighten up its standard and cancel more highway expansions.

“I wish we could stop our use of highways, but we're a long way away from that,” Froelich, the Democratic lawmaker, said. “And until we have really viable alternatives, it doesn't serve us to have clogged roadways.”

While more aggressive policies could bring the 2030 goal within reach, Colorado likely won’t hit its 2025 climate target.

Toor said that doesn’t mean Colorado is “shrugging off” its legal obligation to address climate change. Rather, he said the state is trying to prove it can combat climate change without hurting the economy or sacrificing jobs.

“If you want to actually be successful, you have to do it in a way that works for people, works for consumers, works for the economy, and thus could be a model not just here in Colorado, but for states across the nation,” Toor said.

The acknowledgment has disappointed environmental advocates. Katie Schneer, a senior analyst at the Environmental Defense Fund, said it’s further proof Colorado lacks clear regulations to enforce its ambitious climate targets.

“That’s been the missing piece,” Schneer said.