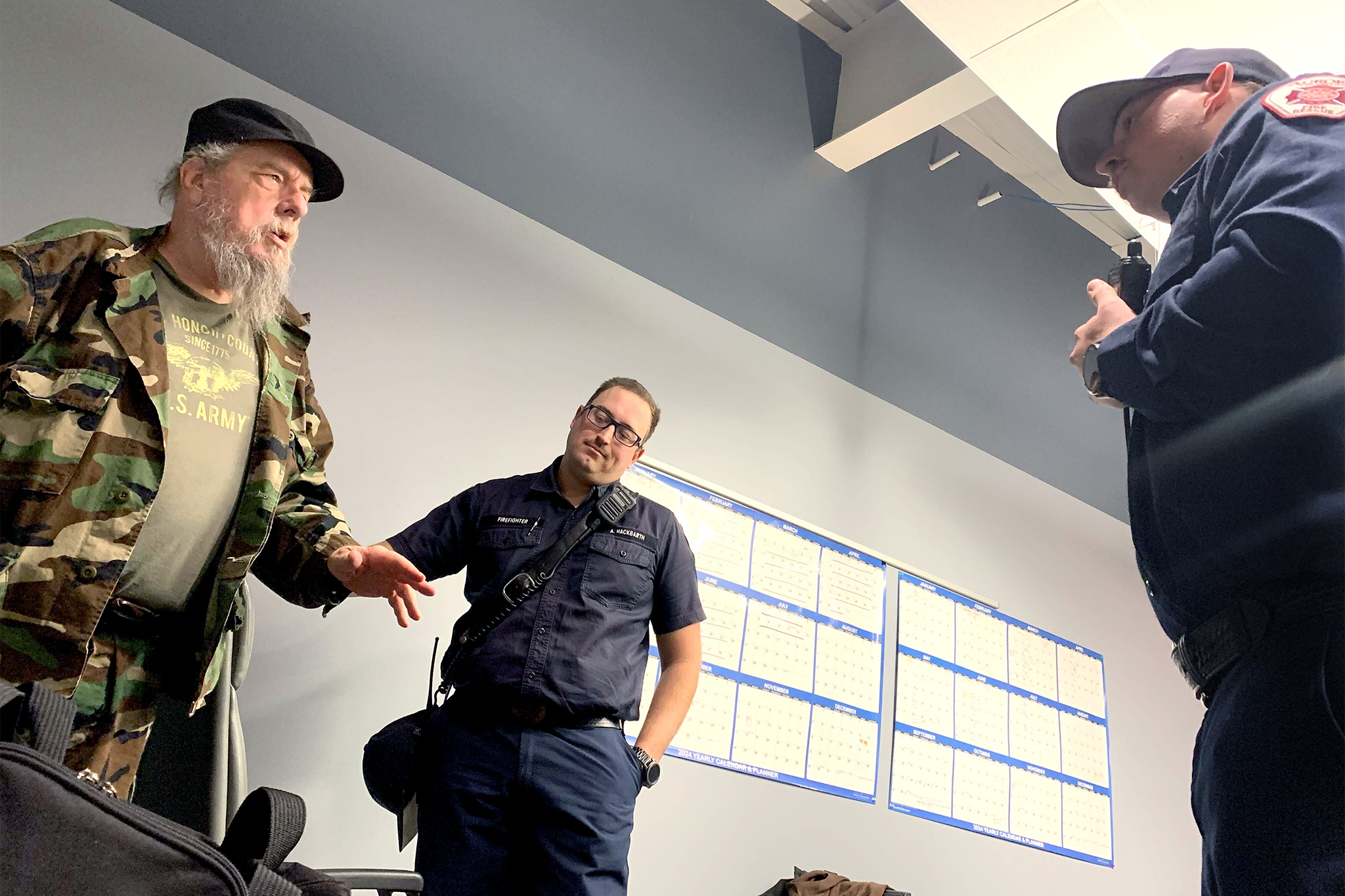

First responders at Aurora Fire Rescue practiced talking to an agitated veteran who admitted to having bullets in a duffle bag by the front door.

“What are all you doing inside my house?” Joe, the veteran, yelled at a group of firefighters and medics while crouched in a corner in fatigues. The rescuers replied respectfully.

“Don’t call me sir! I work for a living!” he barked.

The exercise, played out by actors who specialize in training first responders, was part of a new effort for Aurora’s firefighters, engineers, and medics to go through critical incident scenarios.

“I am hearing banging and voices, are you hearing them?” Joe yelled to the team of four firefighters and medics standing in his living room. “Keep your hands off my bag. It’s got things I need. The three Bs, beans, bullets, and bandaids.”

The fact that this training is happening just a few weeks before a trial was set to start for two Aurora Fire Rescue paramedics charged with giving an overdose of ketamine to an unarmed Black man in 2019 after they were called there by police is merely a coincidence.

However, Aurora Fire Rescue Commander Mark Hays said that case was a big part of the reason they were all there.

In 2022, Aurora Fire Rescue and the state Attorney General’s Office entered into a consent decree that requires both the fire and rescue agency and the Aurora Police Department to improve in several areas, including how they interact with the public and how they hire people.

This agreement was driven by the anger around Elijah McClain’s death and an investigation into both agencies on the scene the night he was stopped.

It inspired Aurora Fire Rescue to treat critical incidents, like McClain’s, differently.

“I’ve always viewed the consent decree as a giant mirror and in it, there was a big critique about how we interact with our community, the police. We looked for ways we could improve upon ourselves and we have looked at improving on the care we provide in the community,” Hays said. “It seemed like the next natural step to do something like this.”

Aurora Fire Rescue paramedics Peter Cichuniec and Jeremy Cooper face a handful of criminal charges including reckless manslaughter and three counts each of second-degree assault for their roles in McClain’s death.

Cichuniec and Cooper showed up on the scene after officers had already forcibly detained McClain and given him two carotid holds, which cut off blood flow to his brain.

Police body cameras show a mostly catatonic, unresponsive McClain in handcuffs as Cichuniec and Cooper administered a too-large dose of ketamine for his body weight. Several medical experts have called it an “overdose” of the sedative. McClain lost his pulse in the ambulance a few minutes later.

In 2020, Aurora Fire Rescue banned the use of ketamine in the field, and, a year later, state lawmakers passed a law limiting its use by first responders and prohibiting law enforcement officers from influencing paramedics’ use of it.

Already, three police officers who were responsible for stopping and restraining McClain were prosecuted. Two were acquitted and one, Randy Roedema, was convicted of criminally negligent homicide.

In hours of body-worn camera footage shown in the first two trials with McClain and police and fire and rescue, it doesn’t appear that any medics or firefighters interacted with him at all. They didn’t take his pulse before giving the ketamine, according to the indictment.

Cichuniec and Cooper are on leave. And although current Aurora Fire Rescue first responders didn’t talk about the pending case, they did say working with police officers in training has helped — and knowing that when officers request them on a scene, as they did on the night they detained McClain, they are the ones in charge.

“If we go to a scene with APD, I ask, ‘Who is the lead on this call?’” said Ryan Wall, a fire medic. “If it’s just officers there, it’s generally, ‘Who is the lead on this?’ Get the rundown from them, then I tell them, ‘Cool, I’m going to take over from here.’”

What happens if the police say they’re the ones in charge?

“Then I’d respond, cool, then why am I here?” Wall said. “It’s not usually a power dynamic. If they ask for us, they need us… If it’s a medical thing, it’s my thing.”

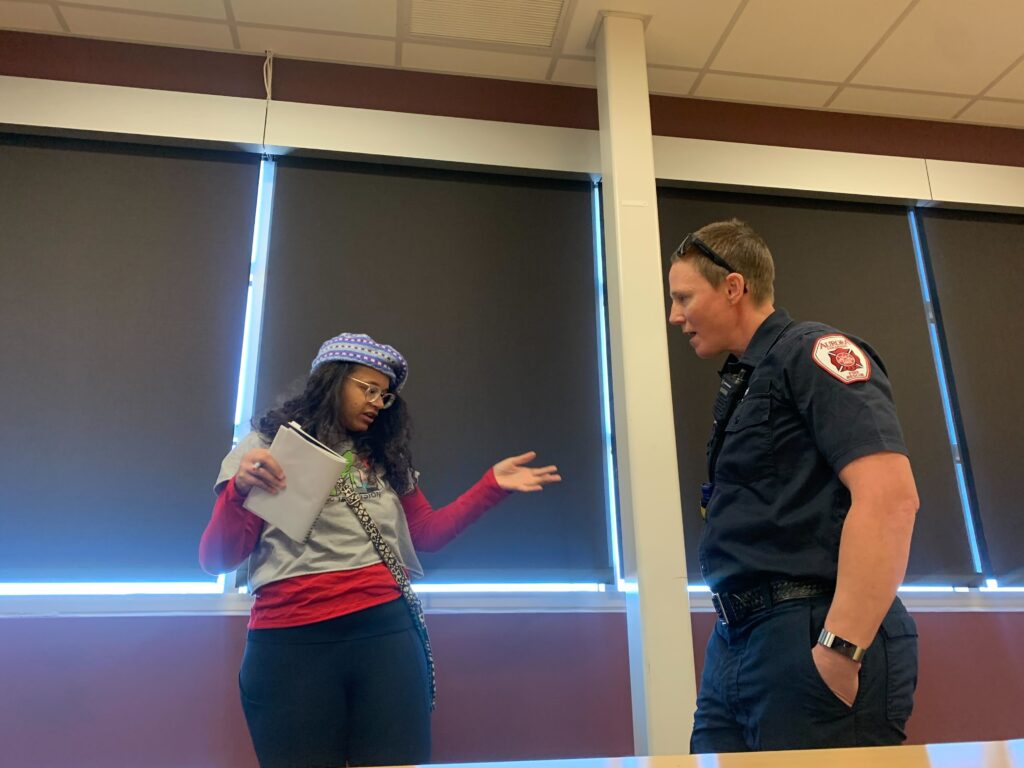

Leanna Elf, a fire medic, participated in the role-playing of a delusional woman who believed the world was going to end as she paced back and forth on the I-225 bridge.

The woman, who didn’t appear to be a danger to anyone but herself, talked to the rescuers about white vans and the voices she was hearing all around her. Elf gently walked to her other side to block her from potentially leaping out in front of traffic or off the bridge and tried to meet her where she was.

“These voices that you’re hearing, are they telling you to do something?” Elf asked.

- What to know about the upcoming trial for the paramedics who face charges in the death of Elijah McClain

- Elijah McClain case: Police officers and paramedics plead not guilty, trials are scheduled

- EMTs should not administer ketamine for ‘excited delirium,’ need bias training, state panel concludes

- Racist Policing And Inappropriate Use Of Force: Aurora Police, Fire Rescue Routinely Violate State And Federal Law, AG Finds

“Yes!” the woman said.

“Are they telling you to hurt anyone or yourself?” Elf asked.

“No, I just need to count the white vans because the end is near,” she said.

In the debrief afterward, Elf said she tries to remind younger colleagues that, in almost all circumstances, time is on their side.

“You rely on a gut instinct. It just comes with experience. It takes seeing it and kind of slowing down,” she said. “Sometimes it takes as long as it takes. I’m personally willing. I have a 24-hour shift… I’m going to take the time necessary to bring a patient into a place where they feel safe.”

Wall, who has been at Aurora Fire Rescue for 10 years, said interactions with the public have changed since the McClain incident.

“There are plenty of people that previously would be agreeable to our help that are not nearly as agreeable to our help because of some of the events that have taken place,” he said. “They may have lost trust in us.”

When asked about morale at the agency heading into the next trial, Wall hesitated.

“I can’t speak to other people’s morale, I can speak to my own,” he said. “I always do what I believe is right and so it’s not necessarily an issue for me because I know what I’m doing is right. Things haven’t really changed for me. As long as I do the right thing, I should be good, right?”