While it’s still unclear whether the two paramedics on trial for giving Elijah McClain a lethal dose of ketamine will take the stand in their own defense, an Adams County jury got a sense of what they may say.

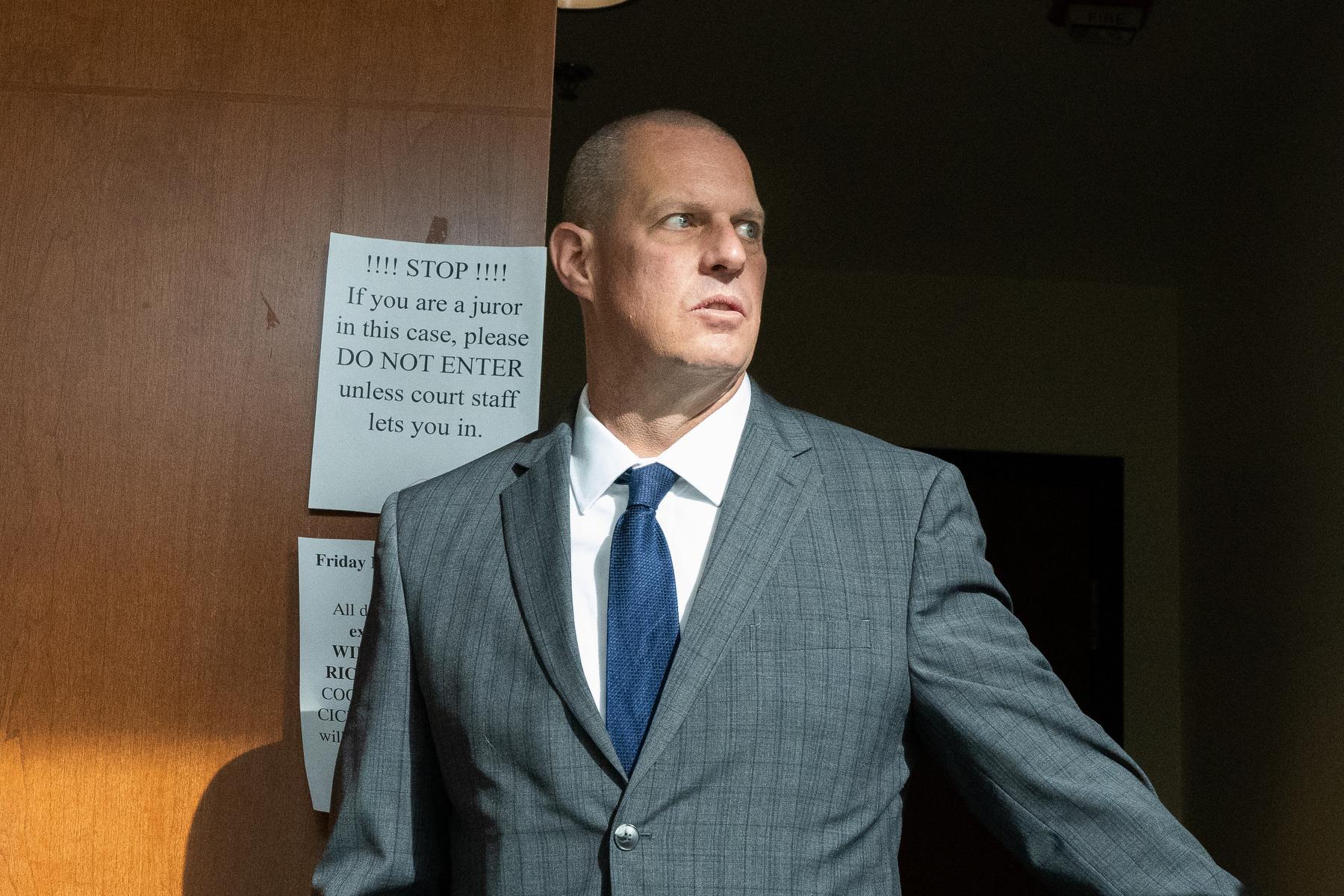

Prosecutors played roughly two hours of video-recorded interviews with paramedics Peter Cichuniec and Jeremy Cooper from the internal affairs investigation run by the Aurora Police Department to the jury on Wednesday.

These interviews happened about two weeks after McClain’s death and were conducted by an Aurora police detective.

In those tapes, Cichuniec and Cooper doubled down on McClain’s “excited delirium” behavior on the scene that night to justify their administration of a high dose of ketamine, a powerful sedative. It had only been approved for use in ambulances the year before because the side effects include slowing down breathing.

Excited delirium is a mostly law enforcement term that has been struck from the language from training documents among Colorado police departments and within Aurora Fire Rescue since McClain’s death.

It was intended to describe someone on drugs who has great strength, and hyperactivity and could be a danger to themselves or the public. But several studies since 2020 have pointed out that the term is not rooted in science and has been overly used to justify the use of force, or in McClain’s case, chemical sedation, against Black and Latino suspects by police.

Cooper and Cichuniec each face several felony charges, including reckless manslaughter and criminally negligent homicide and assault, for their respective roles in McClain’s death in administering ketamine.

This is the third trial prosecuted by the state attorney general’s office in the 2019 death of McClain. The first two cases against the three responding Aurora police officers ended in two acquittals and one officer, Randy Roedema, was convicted of criminally negligent homicide.

Cichuniec told the Aurora Police Det. Matt Ingui in the internal affairs interview that the night McClain was forcibly detained by police was the first time he had used ketamine in the field. Cooper said on tape he had used it before on scenes, he specifically mentioned a guy smoking “spice” having “excited delirium” and receiving ketamine to calm down.

Both Cichuniec and Cooper said when they arrived on the scene, McClain was on the ground, prone, on his stomach, and handcuffed.

Body-worn camera footage shows McClain barely able to speak at this time, much less get up or struggle. One body-worn camera played in all of the trials so far shows the supervising APD sergeant on the scene, Dale Leonard, leaning over to try and talk to McClain, who was unresponsive. He barely had his eyes open. He had been vomiting repeatedly.

But, on the Internal Affairs tapes, Chichuniec and Cooper told Ingui that McClain was exhibiting all the symptoms of “excited delirium” including hyperactive salivation and hyper-aggressive strength.

“So he was actively resisting the whole time?” Ingui asked Cichuniec.

“Correct,” Cichuniec replied.

“Abnormal strength?” Ingui asked.

“Correct,” Cichniec replied. “The police were struggling to control him.”

Body-worn camera footage played in the trials shows police officers fighting with McClain right as they first stopped and violently detained him, well before any medics arrived.

Within the first few minutes of that struggle, though, when three officers were on the roughly 145-pound massage therapist, McClain was given two carotid holds by two different officers and lost consciousness. He was then handcuffed and brought down to the grass outside of an apartment building on the corner of Billings Street and Evergreen Avenue in Aurora.

Carotid holds, which cut blood flow off to someone’s brain and usually cause them to lose consciousness, have been banned within police agencies in Colorado since the incident. But at the time, it was proper protocol for officers to call both paramedics and a supervisor when that use of force was deployed.

However, in the internal affairs tapes, neither Cichuniec nor Cooper mentioned the carotid hold or that being the reason they were called. In fact, it was unclear in those tapes, whether Cichuniec or Cooper even knew McClain had received a carotid hold.

“Did they give you any information at that point when you got there besides his behavior?” Ingui asked Cooper. “So why were you called?”

Cooper replied, “So we were called, I'm assuming because police thought it might be a medical nature of what was going on, of why he was acting the way he was upon our arrival.”

At one point, Cooper told Ingui that McClain attempted to get up and walk away.

“The police … were still actively fighting any, anytime that the patient would try to be placed kind of on his side, he would try to walk up the little grassy embankment, try to fight with the officers,” Cooper said.

Body-worn camera footage shown in this and previous trials doesn’t ever show McClain getting up off the ground after officers took him down and handcuffed him.

Cooper also acknowledged that, before he called for the 500 milligrams of ketamine, McClain wasn’t coherent.

“It didn't seem like he was ever forming any sentences. A lot of gibberish, a lot of yelling, things that I couldn't understand. They weren't words, they were just noises, grunts, things like that,” he told Ingui.

Cooper was the lead medical officer on the scene and made the call to give McClain 500 milligrams of ketamine — a dosage for a 220-pound person, not a 145-pound person.

He said he estimated McClain’s body weight to be “about 200” pounds and that the training they had received from Falck Paramedics on ketamine indicated that if they didn’t know body weight, they should guess on whether it was a “small, medium or large” person. Cooper said he guessed large.

Cichuniec told the internal affairs investigator, too, that they were trained on “rights.”

“Right patient, right drug, right dose, and the right time,” he said to Ingui.

McClain lost his pulse in the ambulance a few minutes after receiving the ketamine and being moved onto a gurney with velcro handcuffs, or “soft restraints.”

Cooper said they gave him two tibia injections of epinephrine, a steroid that is supposed to jump-start a person’s heart. He told Ingui in the interview that they give emergent medications into the bone marrow to get it into a patient’s system faster.

Cooper also said he started suction on McClain, who had apparent vomit and saliva in his mouth, and still intubated him. He instructed Cichuniec to be in charge of his airway and they started several two-minute rounds of chest compressions.

But, as Cooper said, McClain had “flatlined.” Once they got to the hospital, they transferred McClain’s care to emergency room physicians.

“At one point, it looked there was electrical activity in his heart,” Cooper said. “But he had no pulse.”

On Wednesday, several jurors were ill, and one has tested positive for COVID-19. Wednesday night, the Colorado Judicial Branch announced that “due to unforeseen circumstances, court is in recess until Friday at 8:30 am.”

- Ahead of the trial of paramedics charged in death of Elijah McClain, Aurora Fire Rescue practices de-escalation

- Aurora police officer acquitted in Elijah McClain’s death to get more than $200,000 in back pay

- Colorado strikes “excited delirium” from all law enforcement diagnosis, training documents

- Elijah McClain’s mother feels like justice has not been served

- Aurora Police officer Nathan Woodyard found not guilty in death of Elijah McClain

- One Aurora officer found guilty by jury on lesser charges in death of Elijah McClain