By Kate Ruder, KFF Health News

On a recent November evening, Angie Phoenix waited at a pharmacy here in Colorado’s second-largest city to pick up prescription drugs to treat her high blood pressure and arm seizures.

But this transaction was different from typical exchanges that occur every day at thousands of pharmacies across the United States. The cost to Phoenix, 50, who lives in the nearby community of Falcon and has no health insurance, was nothing.

Open Bible Medical Clinic and Pharmacy runs Colorado’s only current drug donation program. Most of the medications it dispenses come from nursing homes across the state.

“We take any and all of it,” said founding pharmacist Frieda Martin, who used those donations to fill 1,900 prescriptions for 200 low-income and uninsured adults last year. Participants pay a $15 annual registration fee for free medications and care at the adjoining clinic.

Drug donation programs like this one in Colorado and one in California take unopened, unexpired medications from health care facilities, private residents, pharmacies, or prisons that pile up when patients are discharged, change drugs, or die, and re-dispense them to uninsured and low-income patients. About 8% of adults in the U.S. who took prescription drugs in 2021, about 9 million people, did not take them as prescribed because of cost, and uninsured adults were more likely to skip medications than those with insurance, according to the National Health Interview Survey.

The programs vary in size but are often run by charitable pharmacies, nonprofits, or governments, and keep drugs out of landfills or incinerators, where an estimated $11 billion in unused medications are disposed of each year.

“We take any and all of it,” Martin says of the medications distributed through Colorado’s only current drug donation program.

Forty-four states already have laws allowing drug donations, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Many programs, like Colorado’s, are small or underutilized. Now, Colorado and other states are seeking to expand their approach.

“Drug donation programs are effective. There is a huge need for them. And there are opportunities for states to help their residents by enacting new laws,” said George Wang, a co-founder of SIRUM, which stands for Supporting Initiatives to Redistribute Unused Medicine, a nonprofit with the largest network of drug donors and distributors in the U.S.

Colorado Senate Majority Leader Robert Rodriguez, a Democrat, said he plans to introduce a bill next year to create a drug donation program to help the estimated 10% of state residents who can’t fill their prescriptions because of cost.

Similarly, legislation in California signed last year allows expansion of the state’s first and only drug donation program, Better Health Pharmacy in Santa Clara County, to San Mateo and San Francisco counties. Kathy Le, the supervising pharmacist at Better Health, said it is in “the early stages” of working with other county-run pharmacies in California to develop similar programs.

The Wyoming Medication Donation Program, based in Cheyenne, uses mail distribution to reach residents, including those in remote parts of the state who may not have local pharmacies, said Sarah Gilliard, a pharmacist and its program manager. The program mails a total of approximately 16,000 free prescriptions annually to 2,000 Wyoming residents who are low-income, uninsured, or underinsured.

“Access is definitely a big consideration when it comes to the design of our program,” she said.

Many of the Wyoming program’s participants are 65 and older, on Medicare, with fixed incomes and unaffordable copays, but Gilliard said there has been a recent increase in participants between the ages of 20 and 40. Wyoming is one of 10 states that have not expanded Medicaid to cover more low-income residents, which could be a factor in that uptick, Gilliard said.

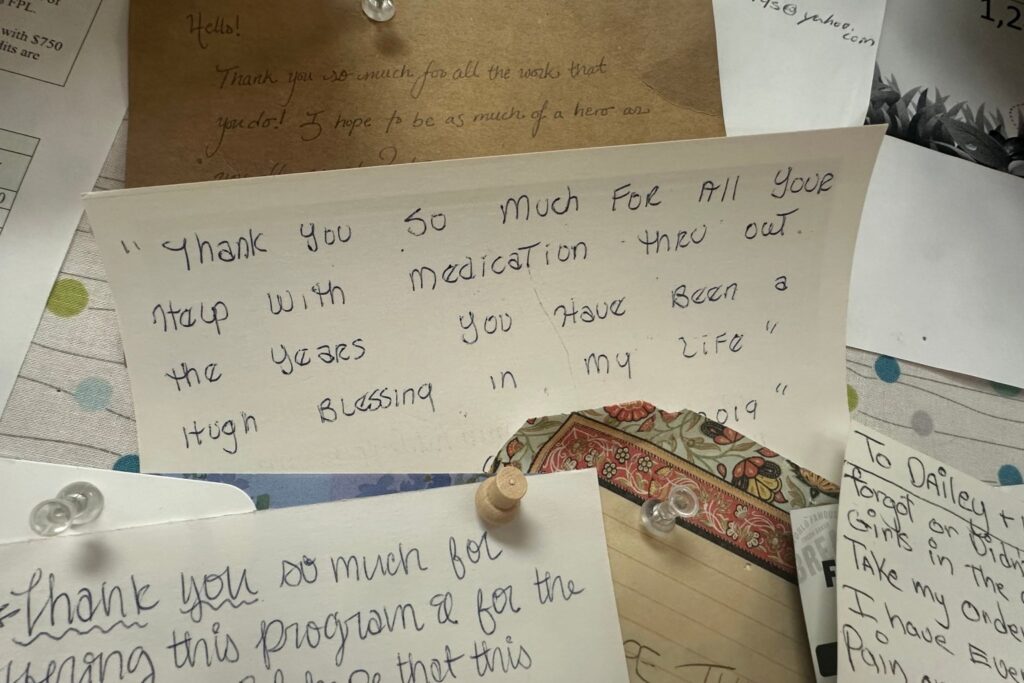

Donations come from all 50 states, with the majority from people who find the program online or through word of mouth. Sometimes donors tuck handwritten notes inside the packages about the high cost of medication or memories of a relative who died.

Gilliard saves each one and tacks them to the pharmacy wall.

Wyoming’s program, with its central state-run pharmacy that receives, processes, and mails prescriptions to residents, could be a model for Colorado, said Gina Moore, a pharmacist and senior associate dean at the University of Colorado’s Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences in Aurora. Moore co-authored a task force report for the state government last December about the feasibility of a drug donation program.

The report noted the success of programs with external funding, which, in Wyoming’s case, comes directly from taxpayer dollars. Using Wyoming’s budget, it projected a Colorado drug donation program would cost an estimated $431,000 in the first year, with a pharmacist and pharmacy technician serving roughly 1,500 patients.

In Colorado Springs, Martin and her husband, Jeff Martin, who is the executive director of Open Bible Medical Clinic and Pharmacy, believe a charitable, volunteer-run model like theirs would be feasible for Colorado, and they wonder how their long-running pharmacy will fit in with potential state-run efforts. In the task force report, Moore and her colleagues write that the state-run model and the Martins’ program could coexist.

Since Colorado enacted a law to allow drug donation in 2005, it has been amended several times in attempts to help it grow. But the state has not invested money or infrastructure to make a drug donation program take off.

The Wyoming Medication Donation Program mails a total of approximately 16,000 free prescriptions annually to 2,000 Wyoming residents who are low-income, uninsured, or underinsured.

“Access is definitely a big consideration when it comes to the design of our program,” says Sarah Gilliard, a pharmacist who manages the Wyoming program.

Drug donations mailed to Open Bible dwindled during the pandemic and are only now slowly rebounding. The pharmacy ships roughly half of all donated medications to clinics across Colorado that serve uninsured and low-income patients in other cities such as Denver, Loveland, and Longmont.

Elsewhere in the U.S., SIRUM ensures that donors have packaging to ship donated medications, and it provides software to make inventorying and dispensing easier. Recently, it built a live online inventory of medications for Good Pill, a nonprofit pharmacy that mails 90-day prescriptions for about $6 to residents of Illinois and Georgia.

SIRUM helps facilitate donations for California’s Better Health Pharmacy, which has dispensed medications to 15,000 Santa Clara County residents since opening in 2015, Le said. Many are uninsured, underinsured, and speak Spanish or Vietnamese. Ten volunteers, often students, help log donations, and Better Health Pharmacy fills roughly 40,000 prescriptions a year with annual operating costs of just over $1 million, according to Le and Santa Clara County public health officials.

Besides prescriptions, Better Health Pharmacy provides free covid antigen tests and flu vaccinations to address its community’s needs. “We try to come up with creative solutions to expand the scope of our services,” Le said.

This commitment to addressing gaps in health care access and reducing impact on the environment means the “timing is right” for expansion of drug donation programs in California and beyond, said Monika Roy, assistant health officer and communicable disease controller at Santa Clara County’s Public Health Department.

“During the pandemic, inequities in access to care were magnified,” Roy said. “When we have solutions like these, it’s a step forward to address both equity and climate change in the same model.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.