AUL Denver student body president J.J. Reed made a mistake — a year ago.

He got in trouble and served three days in a juvenile detention facility. Though he was 17 at the time, Reed wasn’t enrolled in school.

After he got out of juvenile detention, he didn’t bother trying to enroll in a traditional public school. He knew how hard that would be. So, he entered AUL Denver, an alternative Denver Public Schools high school in north Denver that serves students who have faced barriers to succeeding at other schools.

“With AUL, they were a very welcoming community,” Reed said. “The way that their school is designed — they actually accept and help students that have been through the justice system and that have been kicked out or expelled from other schools.”

Since then, Reed has worked on youth-related state legislation, such as a newly proposed bill to bolster and clarify the rights of justice-engaged youth.

“They have a right to an education, and I feel like the right is not given to every child equally,” he said.

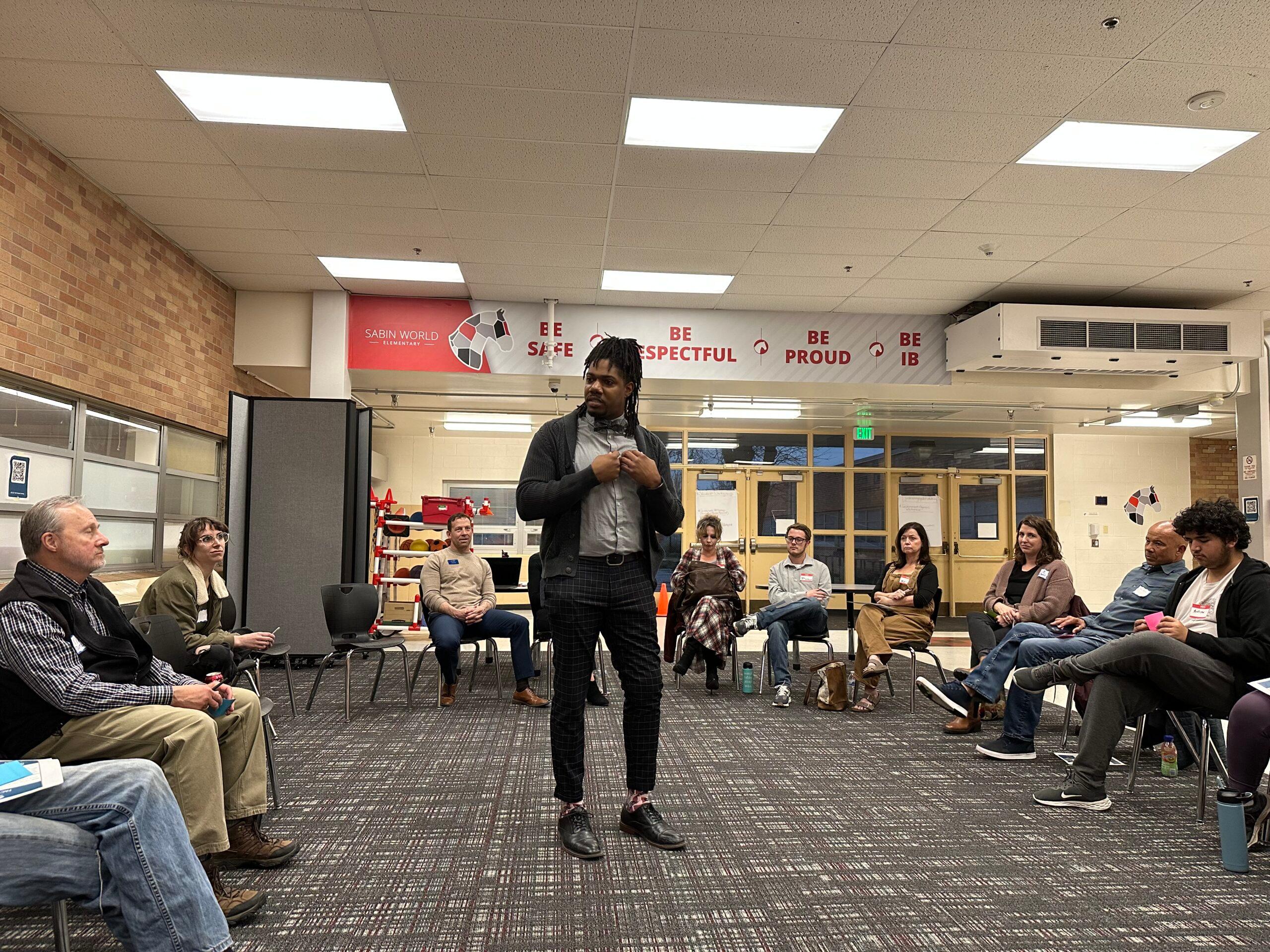

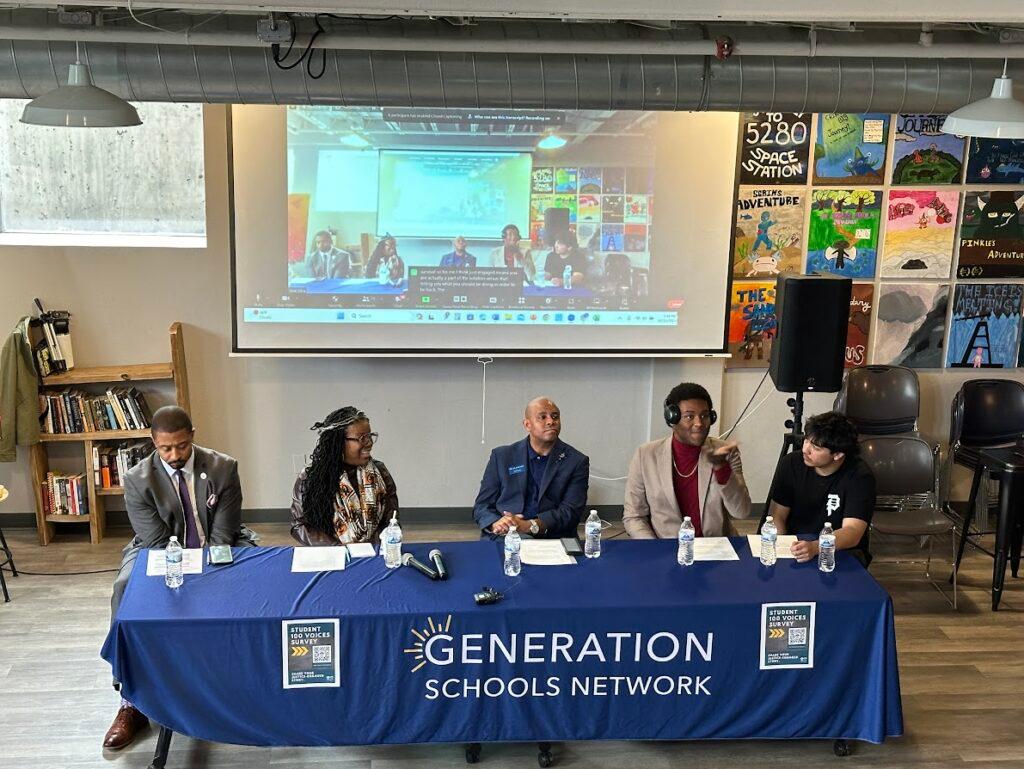

On Thursday, Reed participated in a town hall at Denver’s 5280 High School to introduce the bill and collect further input from students and others. He was joined by Sen. James Coleman and Rep. Jennifer Bacon, who is sponsoring the legislation that some are referring to as a “bill of rights” for justice-engaged students.

The bill, which is still being drafted, will focus on eliminating the confusion and common barriers youth face when they try to enroll back in school. It would likely clarify how academic work transfers between lock-up facilities and districts, designate a navigator to help students transition back to school, track data on how they’re doing and strengthen mental health supports.

Bacon told the audience the issue is about prevention, mitigating recidivism, making youth feel seen and heard in schools, and helping them graduate. She acknowledges that schools need much more support.

“We do need to strengthen the relationships between probation and schools. We do need to strengthen the relationships between (the Department of Human Services) and schools,” Bacon said. “But if someone has served their time, they have already been held responsible …. They are also still kids. Our job is to educate.”

A recent survey of Denver educators found nearly half of them reported that they don’t have the plans they’re supposed to on how to prevent and intervene in discipline issues — like how to deal with serious disruptive behaviors. The teachers’ contract outlines that they’re supposed to collaborate with the school’s principal on the plans, review them annually, and have them presented to educators and staff before the first day of school.

“We're trying to make sure everybody knows what's going to make a difference if you've got students with needs, and how do you support those students?” said Rob Gould, president of the Denver Classroom Teachers Association.

Teachers are also supposed to receive training on restorative practices. The district said in a statement it’s unclear if it has received a list of schools but eagerly anticipates receiving specifics to help make sure educators are aware of their school’s safety plan. The survey showed overwhelming support among teachers for smaller class sizes, and smaller caseload sizes for social workers so they can build relationships with kids. There was little support for the presence of school resource officers or metal detectors.

“We want to fix the school-to-prison pipeline,” Gould said. “We don't want that to happen anymore, and we don't want to suspend students. And in order to do that, we're going to need a lot more support. We're going to need more personnel, more mental health supports. We're going to need more time for teachers to connect with students.”

Bacon said the issue of youth violence intersects with many agencies and that they have to be part of the solution. She recalls a community meeting in 2020 when she asked youth what was behind a spate of youth violence.

“They said, ‘We don’t have people to talk to, we don’t have places to go, we’re hungry or we need support for some of the things we’re facing by way of our health,’” Bacon said. “Our systems are not designed to meet young people where those needs are.”

Bacon said youth have told her they know students who don’t have anywhere to go after getting out of detention facilities or don’t know how to get engaged in school and spiral downward as a result.

“If we can do our part to even save three lives, it’s worth it,” Bacon said.

J.J. Reed was one of the few who successfully returned to school.

Every year thousands of Colorado youth who have been involved in the criminal justice system exit and either never make it back into school, or if they do, never graduate. One study shows that court-involved students are less likely to graduate from high school (20 percent) compared to other youth (74 percent.)

The lost potential is significant. An estimated 22,000 young people in Colorado are justice-engaged through pre-trial, lock-up, diversion and other justice programs. Last year alone, nearly 6,500 youth entered the criminal justice system for the first time.

But it’s unclear what the academic outcomes are for this group of students because those aren’t tracked, according to José Silva, vice president of Generation Schools Network, a nonprofit that works on issues relating to creating healthy school ecosystems. The group has hosted meetings on the issue across the state for more than a year.

“We are asking the community to come together to help solve this challenge because solving it means another $110 million in tax revenue contributed to the Colorado economy over their lifetime,” Silva said.

The Generation Schools Network conducted a two-year pilot that collected data on school interruption. Their study showed if supports are in place and students receive help navigating school after becoming justice-engaged, they can be successful. At the same time, the organization gathered feedback from school district attorneys, advocates who work with at-risk youth, justice-engaged youth, and community members.

“We believe we can remove barriers and dramatically increase educational attainment,” said Wendy Loloff-Cooper with Generation Schools Network. “We know that there is violence in our schools and communities, but if you put a student back into an environment without the support they need, it is an impossible situation.”

Bacon told the youth at the townhall that she is counting on them to tell their stories at legislative meetings this winter as lawmakers fine tune the legislative proposal.

“This bill came from you all, it came from young people, it came from the folks doing this work.”