A new report shows that a postsecondary degree or certificate in Colorado is well worth the time, energy, and money.

The more education workers ages 25 and older have, the more their earnings increase, according to the latest report on the return on investment report by the Colorado Department of Higher Education.

More than 90 percent of jobs that pay a living wage require a postsecondary credential and ninety percent of employers looking to hire say that they can’t find the skills they need across job seekers.

Despite that and the fact that debt among graduates is declining, there are still two available jobs for every unemployed person in Colorado.

Another recently released report shows that while Colorado has made progress on its goal of having 66 percent of the population with a post-secondary credential, it is still largely through the in-migration of people who already have a credential. Undergraduate post-secondary enrollment in Colorado has actually declined since 2010.

The findings appear to dispel myths about the value of college reflected in surveys showing Gen Z is increasingly skeptical about investing time and money in post-secondary education.

“We find evidence that as education increases for Coloradans, annual wages also increase across all industry sectors in the state, regardless of the type of credential one completes,” the report concludes.

Angie Paccione, executive director of the higher education department said learners are demanding a degree or credential that includes skills to enter the workforce.

“We want to give our learners as many options and affordable opportunities to personalize their journey with the resources and social capital they need to succeed and advance throughout their lives,” she said.

Some of the report’s findings

- Last year, those in the labor force without any postsecondary education had median earnings of less than $1,000 per week, compared to almost $1,500 per week for those with a bachelor's degree and more than $2,000 per week for those with a doctoral or professional degree.

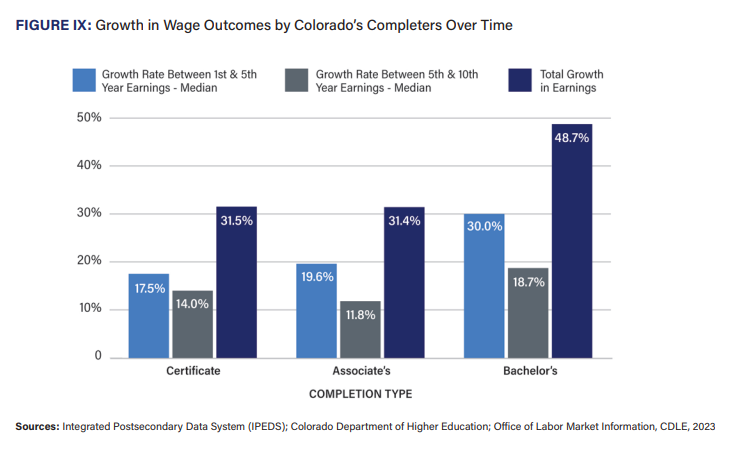

- Short-term credentials and associate degrees result in about a 32 percent increase in median wage levels, while bachelor’s degrees provide a nearly 50 percent increase.

- Sixty percent of businesses reported they were hiring in the first quarter of 2023. Nearly half of those employers have job openings they currently can’t fill, and 90 percent of employers stated they couldn’t find the skills they need across job seekers. The vast majority are seeking skilled workers.

- Of note, the report said that 85 percent of jobs that will be available to the 2035 graduating class have not been invented yet.

Price, debt, choice, value

The report links to an interactive tool that gives users the annual median earnings for Colorado graduates one, five, and 10 years after finishing a credential. It’s based on field of study, credential level, and institution and it represents graduates of Colorado public institutions, graduates of Regis University, Colorado Christian University, and the University of Denver, between 2002 and 2018 who are now working in Colorado.

For example, a two-year associate of applied science in construction trades may start at an average wage of $56,000 and move to $67,000 in 10 years. Meanwhile, a four-year bachelor’s degree in political science earns a bit less, starting on average at $54,000 with a similar average of $67,000 in 10 years. Degrees in the STEM fields pay significantly more.

Colorado students who complete credentials in the following industries are likely to have the highest returns in upcoming years: professional, scientific, and technical services; wholesale trade, finance, and insurance, information management of companies, mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction, and utilities.

Student debt in Colorado is declining

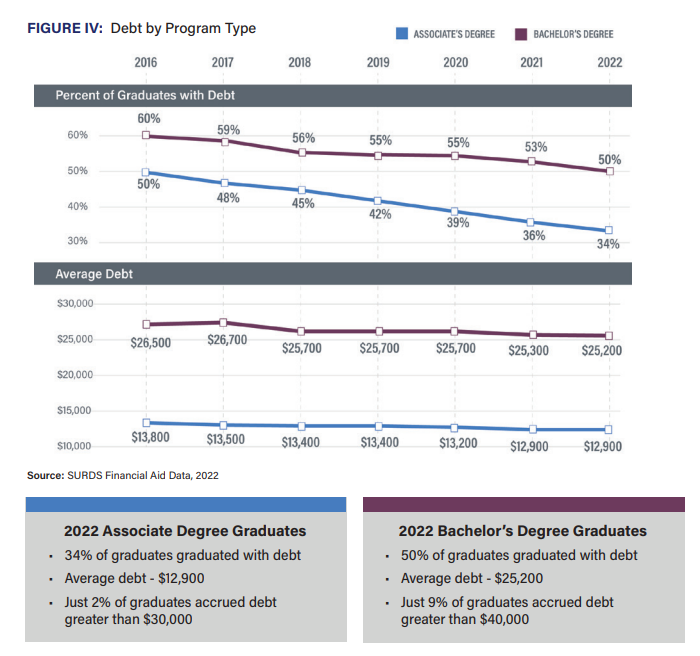

Debt among graduates of Colorado’s four-year schools has declined by five percent among those who attended four-year schools and 10 percent for those who attended two-year schools since 2014. Just half of bachelor’s degree graduates accrued student loan debt, and a third of students who attended a two-year college.

While average tuition in Colorado has gone up over the past 10 years (four-year institutions average $10,900, while two-year are $4,050) few students pay that full amount. Most receive a mix of federal, state, and institutional grants and scholarships.

Most colleges in the state have special programs for low-income students. Metropolitan State University of Denver, for example, reports that students this fall paid an average out-of-pocket cost of about $1,100 for tuition and fees. A quarter of all students paid nothing through a program called the Roadrunner Promise.

CSU Pueblo Colorado Promise covers tuition for full-time resident students earning less than $70,000 who maintain a 3.0 GPA. Adams State has a program that covers tuition and fees and offers a room and board discount to students who enroll full-time from Alamosa and neighboring San Luis Valley counties.

The report notes that living and other costs increase the cost of attendance significantly. Data show the extra time it takes many students to finish a degree reduces the return on investment. Students also often complete more credits than are needed to graduate.

One new trend is that learners earning short-term certificates are completing them faster compared to the pre-pandemic era, which the report attributes to the growth of industry-recognized micro-credentials.

What’s the state doing to help meet the demand for skilled workers?

The state is working on multiple fronts. Lawmakers have passed dozens of pieces of legislation focused on workforce development and career pathways in secondary school and community colleges.

It also invested $65 million to offer free training for students pursuing in-demand jobs. More than 3,000 Coloradans have already completed programs for in-demand jobs in the health care sector.

The state has an updated strategic plan that aims to channel more Coloradans into post-secondary fields that will provide them a good-paying jobs. But the fact remains, that fewer than one in three high school graduates get some kind of post-secondary credential. The plan calls for institutions to prioritize pathways that lower student costs, invest in learner support programs, and increase collaboration with employers.

A legislative task force that met 15 times this past year just released a report showing there is still a disconnect between secondary, higher education, and businesses. It has a host of recommendations, including streamlining programs under one umbrella and raising public awareness of work-based learning programs.

Colorado has also put $85 million into the Opportunity Now grant program. It provides incentives for innovation between education and employers to grow the state’s talent pool.

And now many high schools now offer programs that provide postsecondary credentials for free to high school students. That makes students more competitive in the labor market right when they graduate, according to the report.