For the first time, the state’s flagship university has someone to oversee its relationship with tribes. Benny Shendo Jr. was hired in the fall to be the University of Colorado’s new associate vice chancellor for Native American affairs.

It’s Shendo’s second stint with CU — the first coming nearly 40 years ago when he was a student-athlete studying business. He returns years later, with decades of experience as a New Mexico lawmaker, higher education administrator, and tribal leader under his belt.

His appointment comes just a few years after Colorado made it easier and cheaper for Indigenous students from tribes with historic connections to Colorado to attend in-state universities. The university has taken that seriously and sees Shendo’s appointment as just one step it will take to grow its Indigenous student population.

Shendo spoke with Colorado Matters senior host Ryan Warner about how he’ll help CU expand its Indigenous student population and the challenges tribal entities face that higher education can address.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Ryan Warner: You first came to CU Boulder in the 1980s from Jemez Pueblo in New Mexico, studied business, ran cross country. Your Pueblo has fewer than 2,000 people. CU’s student body is at least 20 times that size. What was the hardest thing about that and what worked really well back when you were a student?

Benny Shendo Jr.: That's a good question. I come from a small community, remote village in the mountains, and I've always had my heart set on coming to CU when I was a high school kid and I didn't know how I was going to get there, but I knew I was going to be there at some point in my life.

It was quite a journey. And my high school graduating class was I think 21 students. But my journey to CU, I had a stop at Colorado College, so it made the transition to CU a lot easier.

It was kind of a middle landing place.

Shendo: Yeah, Colorado College had the block program, so you took one class for three and a half weeks and you don't have to worry about juggling any courses and so forth. So it made that transition a little easier.

And then of course when I went to CU, it was huge. Some of my earlier classes, I remember there's a few hundred students in those classes and so forth. But I think what made my transition a little easier, I was always interested in running cross country. So I visited with the coach, allowing me to practice with the team. And so it's a little easier when you have sort of almost like a ready-made family. You have coaches, you have friends that you meet that are on the team, and stuff like that.

So having those relationships established, feeling like that's already potentially a home for you, how do you think you might apply that now in leadership to perhaps indigenous students coming to Boulder for the first time?

Shendo: Back then there was a fairly good sizable Native American population as well. My sister, and then a few others had gone to CU as well. It was a sense of community, and I'm hoping that we can establish that for any student, whether they're Native, non-Native, because having that ability to identify with a place and feel like you're a part of it and accept it, is good for every student.

But I think in particular for Native students who may come from small schools, rural areas, and really strong family connections and not having that on a campus sometimes could be an issue. And so my hope is that we can reestablish some strong Native support programs on campus, both at the undergraduate graduate [level] as well as our staff and faculty, and try to increase the recruitment of those folks so that we have a much larger community.

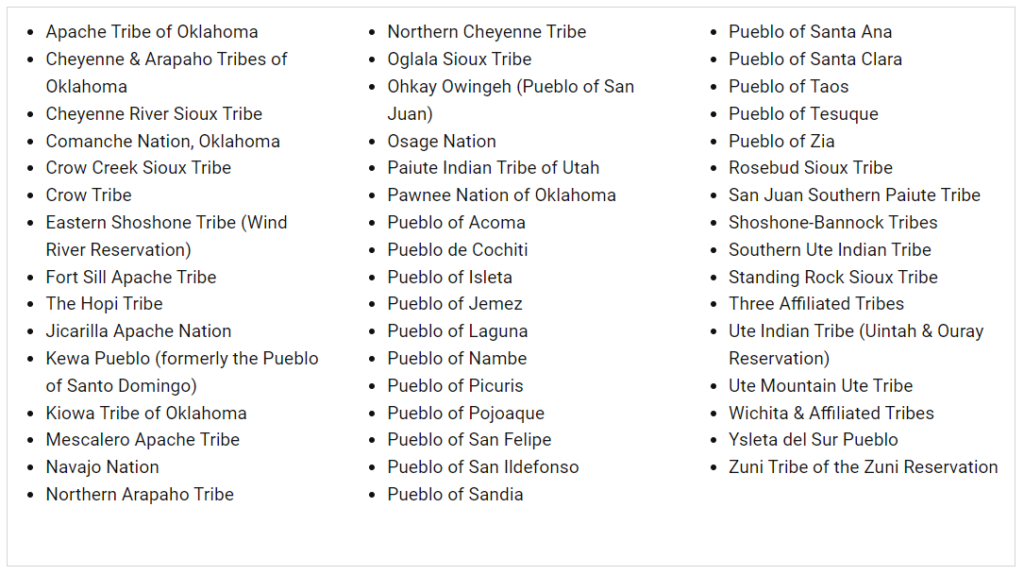

A few years ago, Colorado lawmakers passed a bill to give in-state tuition to members of indigenous tribes with historical ties to Colorado, 48 nations altogether on that list. How strong are CU's relationships with those tribes?

Shendo: It's hard for me to gauge. I think over the years, certainly, the university has had relationships with the Ute and the Southern Ute tribes but those are the only two federally recognized tribes that are in Colorado. The rest of 'em are elsewhere. And so I think the relationship has always been there.

That’s your strongest?

Shendo: Those are the two probably strongest. And then I'm hoping that with this new law and my outreach and my connection to Indian country, we refer to as Indian country, I know a lot of leaders from the other tribes that have interacted over my course of being involved in higher education as well as in the political arena, and also involvement in the National Congress of American Indians, which is a national organization that I belong to as well.

So those connections are going to be really meaningful and helpful as we try to establish a stronger connection. They're really a government-to-government relationship. I think the university, at least through the museum and the NAGPRA program, which is the Native American Graves Protection Repatriation Act, has had very good ties to repatriate some of the things that the university has with these tribes and so forth. So I think there's always been a relationship.

This is a really important point because the relationship between CU and the tribes is not just about students, right? It's about artifacts. It's about what belonged to tribes that universities had in their storehouses, for instance. There's some complicated history between these governments.

Shendo: Correct. Universities are typically large repositories of these remains. In fact, I was a second lieutenant governor back in 1998, and in 1999, we finally brought home over 2,000 of our ancestral human remains back to Pecos Pueblo, New Mexico, which is east of Santa Fe.

That was almost a decades-long fight and the work with the Harvard University and Peabody back east. And so I'm very familiar with that whole process. It's complicated. It's a tough issue for us to address because the proper burial rights of our people have already been performed. And so how do you do that the second time when you have to reinter that many human remains? And so that's always a difficult situation, I think, for tribes.

Thank you for that context, chancellor. I do want to know what tribes ask of you, ask of CU when perhaps you talk about the sorts of jobs they need young people to train for, what their needs are in terms of workforce.

Shendo: I think that's going to be an important part because the capacity of tribes, all professions is needed. In fact, I was a tribal administrator for my Pueblo for six years and basically ran the operations for the tribe and extraordinary need for people in finance and management in business, in grant writing because there's so many opportunities that are foregone because people just don't have the capacity.

We're dealing with climate initiatives right now, we're looking at transition from fossil fuels to other new forms of energy. Tribes don't want to be left behind, but the capacity of folks to move on those projects sometimes is not there.

And of course, you hear about some of the tribes of some of the largest employers in their region. And with development, diversification, there's a huge need. And I think the universities, all universities, not just CU, I think all have a role to play in the development of students to hopefully tackle some of these issues in the future for them.

That's interesting because the development of the students might inform the further development, economic development of reservations, of tribes, of lands, of nations.

Shendo: Yes, that is. But I think one important perspective we also have to keep in mind is that not just economic development, but development of our communities, the whole resurgence or the importance of reclaiming your language and things are important as tribal nations.

I think historically, education has always been about assimilating us into the larger society. And the struggle and the fight has always been about us reclaiming who we are, our language, our lands, our sacred sites, our songs, and all the things that make us who we are as Native people.

We see more and more tribes now looking to reestablish language immersion schools because this is something that was taken away by the federal government in a very systematic way. And now we just don't want to develop economically and lose a sense of who we are and our identity as a Native.

That there be the cultural element to this. I know for instance, there's an Arapaho language program at CU, but 48 nations altogether that have historical ties to this place, how do you build that in and recognize the differences among all of these nations at a school like CU Boulder?

Shendo: There are very distinct differences between tribes, but also I think look at these issues, there’s certain commonalities that we also have, so how do we look at those as we develop, whether curriculum, its language or things that we want to do at a CU or any university, is how do we take that approach and work with tribes to engage them on a government to government level because they are sovereign governments. And I think a lot of times people forget these are tribes that are sovereign nations within our own states, within our own country. And to recognize that any engagement with the tribes, we have to do it at that level.

So do you imagine visiting tribal elementary schools, middle schools, high schools, how far back in the pipeline do you want to get?

Shendo: My role as vice chancellor, I love the communities that as a state senator, I've visited many of these communities. And so for me, coming from New Mexico, all the tribes in New Mexico have historical connections to Colorado, and they are the ones that are going to be able to benefit at least the students from those tribes with the in-state tuition and so forth. And then of course, we've got tribes in Arizona, Oklahoma, Wyoming, Utah, South Dakota, Montana, North Dakota, and Idaho as well.

You have some traveling to do.

Shendo: Yeah, I’m pretty excited about that. I visited most of the tribes in Arizona and Mexico, not so much in Oklahoma. I've been to Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, and I've been to South Dakota, so I've got friends there. And I think a lot of folks are excited about what's happening at Colorado and with my role.

What are they excited by? There are presumably other schools, including the University of New Mexico, who would be all too happy to have these students as well.

Shendo: I worked at the University of New Mexico. I worked at Stanford Assistant Dean of Students. So I know how to establish these programs. I know how to develop programs. I know how to raise money for these programs.

I think that's the excitement because we never really had a person at this level, at the university to really forge these types of opportunities working with our university, our staff, our various departments, our various schools to really pursue some of these things.

So your presence and this position is a game changer, you think?

Shendo: I think so. I think that's what I'm looking at it. Boulder, Denver, this area has always been a crossroads of Indian country and it's really fascinating, when I was an undergraduate student, we had some very strong organizations that were national nonprofits, and we still have some here.

The Native American Rights Fund is right there in Boulder. The Council of Energy Resource Tribes was headquartered here in Denver. The American Indian Science and Engineering Society still has headquarters in the Longmont Boulder area. The First Nations Development Institute, which is a national nonprofit, has its headquarters in Longmont.

So you have a crossroads of these large national nonprofits that have impact across the country. And then you have not only the University of Colorado, but we also, you have the Denver schools. You have Colorado State.

Isn’t the American Indian College Fund in Boulder too? Did you mention that one?

Shendo: No, I didn't. I'm sorry. I'm glad you did, right. The Native American College Fund is in Denver, just up the road here.

So you have the presence of these organizations. So you have a lot of, I think the ability to leverage that work to create new opportunities. And how do we develop these programs, whether they're on campus and off campus to support students.

Would you hope to make CU a Native American-serving non-tribal college? I'll say that's a designation from the US Department of Education. And I guess either way, do you have a number or percentage in mind for an Indigenous student body?

Shendo: That's always hard because you have students that are enrolled in tribes. You have students that have historical connections to tribes, but they're not necessarily enrolled. You have tribes in the past that have been unrecognized by the federal government, so they're still trying to fight for recognition. So it's always a hard number to do but I think the important thing is for students that identify themselves as Native and so forth, that to me is the most important. They want to be a part of a community to strengthen, to make sure our students succeed. To me and I think whether it's students and faculty and staff, that's really most important for me.

When you look at the staff, when you look at the faculty at Boulder today, do you see enough Indigenous faces?

Shendo: No. I mean, we got a lot of work to do, and I think Boulder's a great place, but at the same time, it's a pretty expensive place, and the cost of living in this area is always going up. And so I think as a university, we have to look at ways to be attractive, both bring folks on, but also how do we support them?

What you're saying there is an obstacle to being on faculty, on staff at CU Boulder is the inability to live there, to afford a place to live there. Is that in your purview?

Shendo: That's probably outside, yeah. I think the university is doing stuff to make housing affordable for students. I know there's graduate students and then also I think there's faculty housing stuff in the past. And so all that stuff is, I think, being looked at right now.

But you'll be adding your voice, I suppose, to the call for that?

Shendo: Exactly, yeah, to be part of that discussion and voice is going to be critical.

Could CU Boulder be more affordable for students, for Indigenous students? The in-state tuition no doubt helped.

Shendo: It definitely helps, but still, it's a big ticket. It's still talking $30,000 even at in-state, I think. And so I think part of our challenge is to raise hopefully, scholarship dollars to support the students. Some students may come with their own dollars, like the Navajo Nation, they have the Manuelito Scholarship. So if you're a Navajo student and you have a certain level of, I think GPA or SAT or ACT, you're automatically awarded this Manuelito scholarship that can follow you wherever you go.

So there's going to be students that are able to get supported by their respective tribes, but for those that come from families or tribes that don't have the resources, it's going to be a challenge. And I'm hoping that we can be able to package those students in a way that makes it affordable for them.

Colorado is also home to Fort Lewis College, which awards more degrees to Native American students than any other four-year school in the country. Is there something to learn from the folks in Durango?

Shendo: Certainly. I think they’ve got good support programs. They've done very well. Some tribal members from our tribe have graduated from Fort Lewis. My youngest sister graduated from Fort Lewis, and so there’s a lot I think we can learn but also, one of the things that I look at Fort Lewis is the potential for graduate students. They don't have many of the graduate programs that CU has.