How to handle the influx of migrant students into Denver, Aurora, and other metro schools is quickly becoming a statewide issue.

State education officials said they’re exploring ways to get more state funding for districts that have seen an unprecedented influx of thousands of new migrant arrivals – and they’ve convened a working group of school districts to figure it out.

The discussion around migrant students was after a presentation Wednesday to state education board members by the state’s demographer about what to expect for school enrollment in the coming years. A survey of about a dozen districts by CPR shows more than 6,000 new migrants in schools since the summer.

“How do we support these sudden shifts in the demographics that are happening within our schools, within our sphere of influence?” asked state board member Lisa Escárcega.

Many migrant students arrived after the state’s October count date, which is used to determine per-pupil funding.

“It is very real the impact that new arrival students have to schools both if they’re here for October count but particularly if they’re not here for October count,” Commissioner of Education Susana Cordova told the board.

The arrival of students after October in the state's largest school district is an estimated $14 million in revenue that the district hasn’t been able to claim.

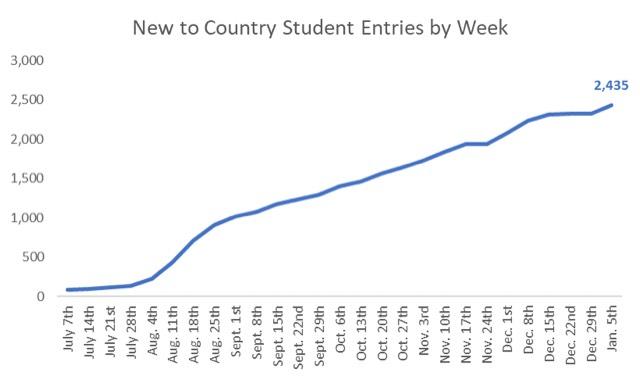

Denver Public Schools has enrolled more than 2,400 new students since July. Those are students who have stayed; the number doesn’t include students who enrolled and then moved on to other cities in Colorado or elsewhere in the country.

The district continues to receive about 100 new students a week. The schools that have bilingual and other services for newcomers are particularly strained. Some schools are reporting kindergarten classrooms of more than 30 students.

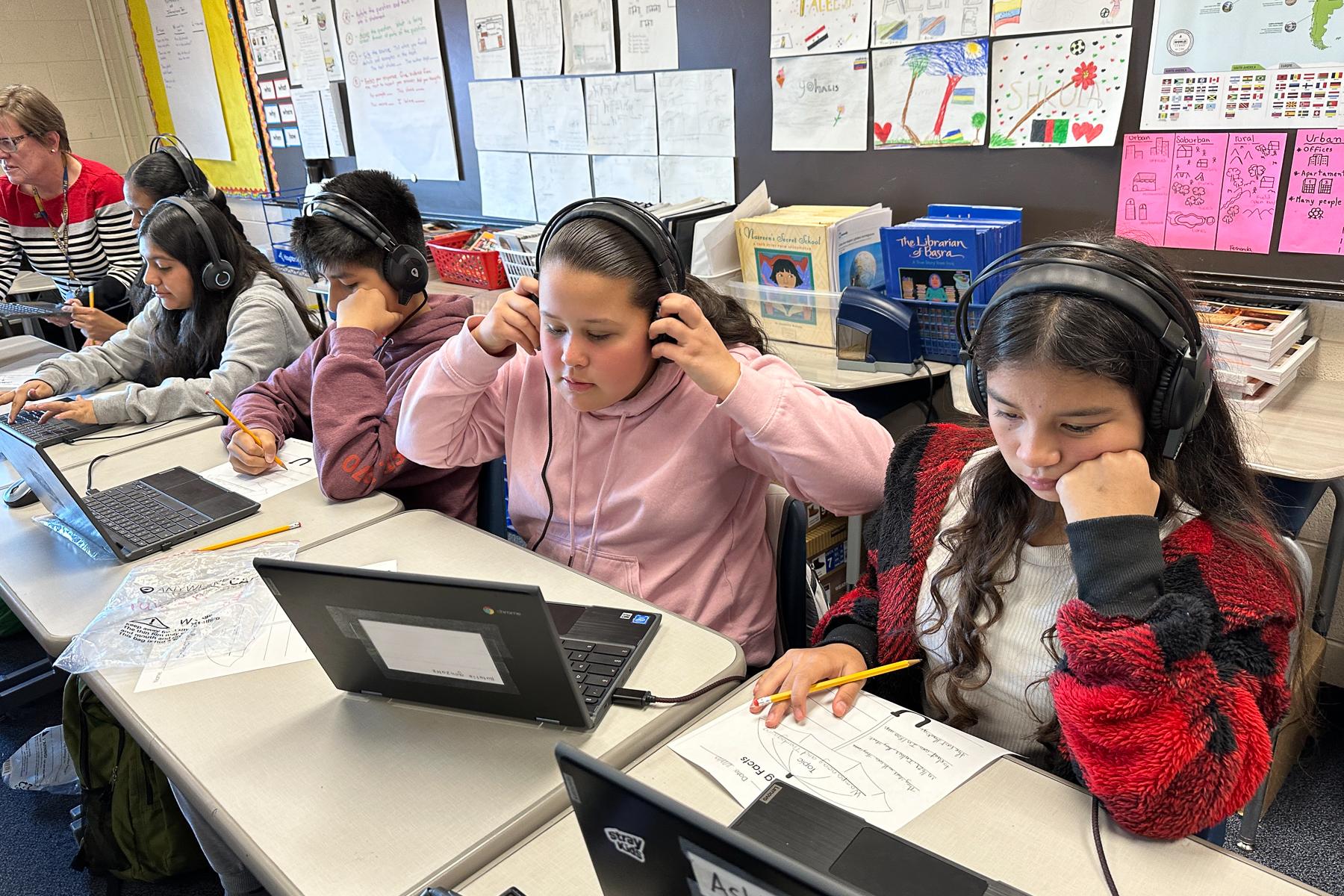

Classrooms can be chaotic at times when many of the new arrivals have either never been to school or have missed more than a year of school, alongside a shortage of bilingual teachers and classroom aides. Cordova recently visited Abraham Lincoln High School in southwest Denver, which was already the school receiving the largest number of students who speak another language.

So far this year, it has about 125 new students from other countries, about 15 percent of the school’s population. Some have experience in school; others have been out of school for 12 to 18 months, she said, “very different conditions than what we have typically grappled with.”

It’s unclear whether additional state funding could be on the way. Cordova said state officials have been in discussions with the governor’s office of planning and budgeting on whether more money could be allocated for impacted districts. State officials said they have been reviewing student enrollment since October to make sure districts have the support they need.

Cordova said another challenge will be recruiting bilingual teachers or educators trained in teaching English as a second language given the state is experiencing a critical teacher shortage.

Board member Angelika Schroeder said she learned that more than a dozen districts have stepped forward to receive students who would typically enroll in DPS and Aurora schools.

“That should take some of the pressure off in terms of what’s happening in Aurora and Denver,” she said.

Thousands of new students have also changed the equation for many under-enrolled schools facing the threat of closure. Escárcega said one of those schools has enrolled a couple of hundred more students this year and is now considering a cap.

She asked the question on the minds of many educators: What is the forecast for more new arrivals so educators can plan and prepare?

Unfortunately, state demographer Elizabeth Garner said it’s impossible to forecast because many decisions impacting the flow of migrants are made nationally and reflect international turmoil. Typically, Colorado has not been a top state for international migration, she said.

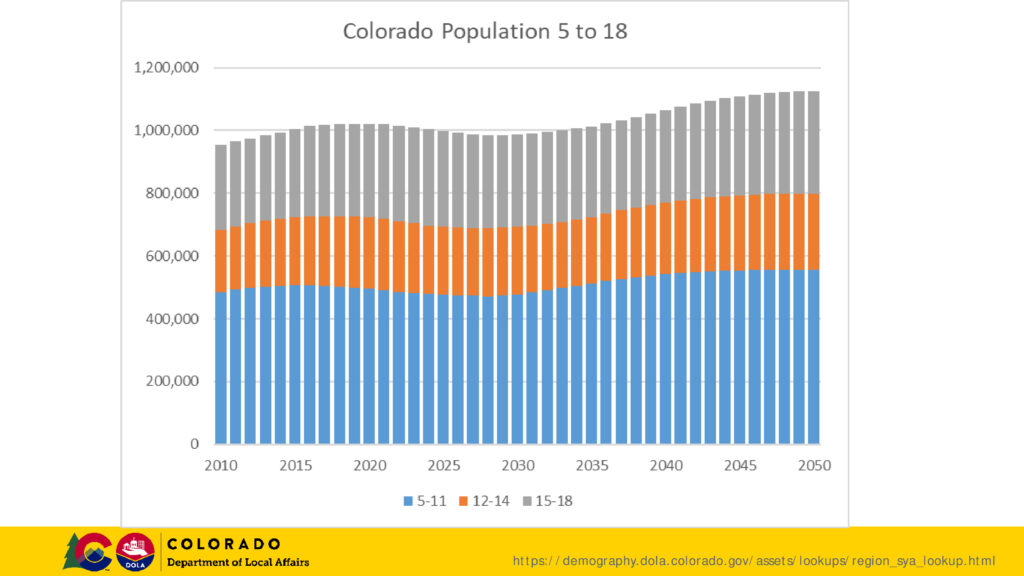

The school-age population overall, however, is still declining

New migrants aside, slowing birth and migration rates will continue to influence Colorado’s school-age population, according to Garner.

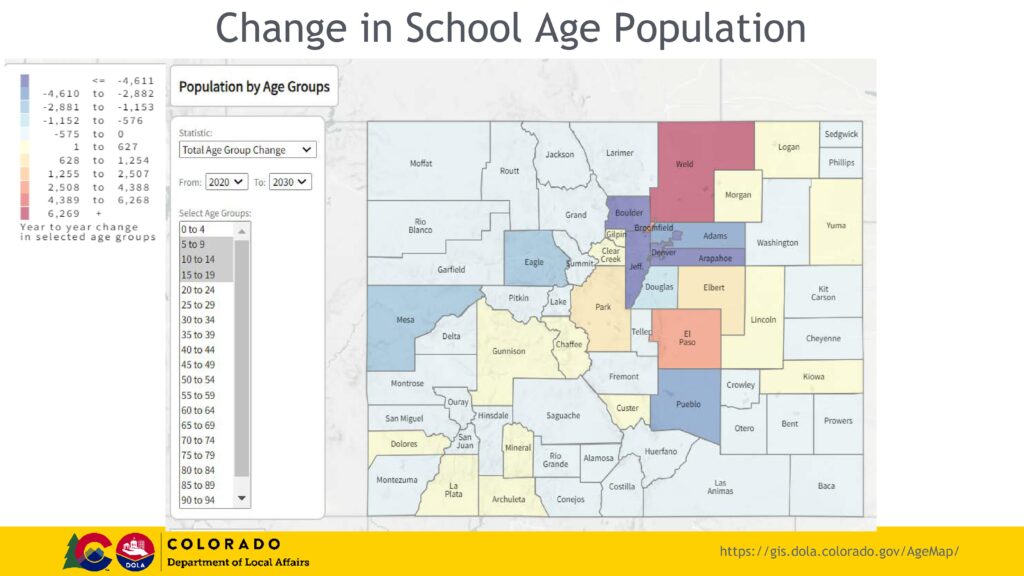

Colorado was the sixth-fastest growing state in the country from 2010 to 2020. The state was adding about 75,000 new people every year but that number has dropped to an average of 30,000 so far this decade. Garner said nearly two-thirds of Colorado’s counties have seen declines in the school-age population over the past decade. Weld County is seeing growth, however.

Garner told board members to expect the number of schoolchildren to keep declining through 2028 or 2029. Enrollment won’t get back to 2020 levels until 2035. In higher education, population drops in California, the Midwest, and the Northeast could impact Colorado because they are the regions that send the most students to Colorado’s colleges and universities, and move here to fill jobs.

“But don’t be too sad, Texas is still growing and Texas is one of our largest donor states as well,” Garner said.