CPR News has spent months talking with teenagers, parents, doctors, advocates, researchers, political figures and others. We’ve looked through once-secret internal industry documents released by tobacco companies and listened to many hours of city and legislative debate. What we found is that the conversation about tobacco products, especially flavored ones like menthol, is not only about nicotine’s deadly effects or the impact on local economies. It’s about ethics, optics and equity.

At the University of Colorado in Boulder, a group of undergraduates with the school’s Health Promotion program sets up shop in the music building. Here they talk peer to peer to other students in what’s called Buffs Discuss.

On a table, there’s literature, protein bars, sodas, an overdose-reversal kit.

A senior starts a confidential survey with a freshman.

“So what would you say your most used substance is? Alcohol, marijuana, nicotine,” he asks.

The responses often touch on all three. And, according to sophomore Sage Heuschkel, students say nicotine use, and vaping, is common.

“Vaping at a party, wouldn't be surprised if it was half,” were doing it, he said. Some own their own device, others borrow. “They're like, ‘oh, let me try. Let me hit your vape.’”

Senior Jacob Garza said for many young folks on campus, it’s a long-standing habit.

“Everyone knows it's not good for you and everyone wants to stop. But at this point, doing it all these years, it's not like muscle memory, but it's just second nature now,” he said. “They're hooked on it at this point.”

Data from the state health department show adult vaping rates are rising in Colorado, driven by a sharp increase among young, college-age adults, those 18 to 24.

The department’s Tiffany Schommer, the tobacco cessation supervisor, said a quarter of that group now vape regularly.

“E-cigarette use has increased, particularly among people who have never smoked,” she said. “So these are folks who started with vapes, continue with vapes.”

Vape rates, she said, have actually dropped among Colorado high schoolers and middle schoolers.

The figures were highest in 2017, according to the Healthy Kids Colorado Survey, when 27 percent of Colorado youth were vaping within the past month.

But by 2021, the most recent year for which there’s data, the figure had dropped sharply to 16 percent, which is about one in six.

But the share of those 18-24 that regularly vape rose about 60 percent in just two years, during the pandemic, from 2020 to 2022, rising nearly 10 percentage points from about 15 percent to almost 25 percent.

'They weren’t able to stop.'

In a Children’s Hospital Colorado exam room, pediatric pulmonologist Dr. Heather De Keyser shows a clouded X-ray of the lung of a young adult damaged by vaping.

“This is a patient with vaping-related lung injury,” she said, pointing to a computer screen.

For years, doctors like her and public health experts wondered about the potential harmful impact of vaping on pre-adult bodies and brains, including the risk of addiction

“I think, unfortunately, those lessons that we were worried we were going to be learning, we're learning the data is bearing out in that,” said De Keyser, an associate professor of pediatrics in the Breathing Institute at Children's Hospital Colorado. “We're seeing increases in those young adults. They weren't able to stop.”

Another thing that pops out in the data is that adult e-cigarette users often engage in what’s called co-use, vaping not just nicotine but marijuana, binge drinking and/or smoking cigarettes. Among adult e-cigarette users in Colorado in 2022, about six in 10 also used marijuana, four in 10 binge drank and a quarter also reported using cigarettes.

De Keyser said it’s a concern as teens age into young adults.

“There's a really significant link between mental health and vaping,” she said. “And quite frequently vaping in teens and young adults is seen as this way to cope with stress and cope with mental health challenges.”

It’s no coincidence the numbers soared during “the COVID time,” the pandemic, according to several public health experts. Students across the board the past couple of years have talked about the isolation and use of many substances rising, said Alyssa Wright, Early Intervention program manager at Health Promotion at CU Boulder.

“Just being home, being bored, being a little bit anxious, not knowing what's happening in the world,” Wright said. “We don't have that social connection, and it feels like people are still even trying to catch up from that experience still.

A couple of other factors are key, the high nicotine levels and “stealth culture,” said Chris Lord, CU Boulder’s Associate Director of Alcohol and Other Drug Programs and Collegiate Recovery.

“The products they were using had five times more nicotine than previous vapes had,” he said. “So getting hooked on that was really, I mean, almost impossible, to avoid if you're using something like that.”

Plus, vaping was seen as exciting, as something you’re not supposed to do. “I think as an adolescent, our brains are kind of wired that way, a lot of us,” Lord said.

The role of the JUUL Revolution

Wind the clock back half a decade and one can see the seeds of the trend.

Type the word JUUL into a browser on YouTube and see endless videos of young people showing off how cool it was to use the company's sleek, high-tech-looking vaping device.

In one video CPR found in 2019, a pair of young women welcome an online audience before they show how they “make parties more fun.”

“We just chillin.’ We vapin’ and we JUULin,” one said with a laugh.

Many of those videos are no longer available, pulled off the site once the trend took off, now replaced by ones warning of the dangers and how to talk to kids.

In lawsuits, local governments nationwide and states, including Colorado, sued, alleging JUUL Labs misrepresented the health risks of its products. It had become No. 1, the top e-cigarette company, the suits argued, by first aggressively marketing directly to kids, who then spread the word themselves by posting to social media sites like YouTube, Instagram and TikTok.

At one point, before the pandemic, Colorado led the nation in youth vaping, topping 37 states surveyed for use of electronic cigarettes among high school students, according to numbers from a CDC study. A quarter of those Colorado students said they currently used an electronic vapor product — double the national average. Almost 6 percent said they used them frequently.

“What vaping has done, getting high schoolers, in some cases even middle schoolers, hooked on vaping, is now playing out,” said Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser, a parent of two teens himself. He said vape companies followed the tobacco industry playbook with a similar impact on young consumers. “They're still hooked. This is a very addictive product.”

“All these social media platforms really made everything look quite stylish and sexy,” said CU’s Wright. The idea was “making it look cool,” she said. “It worked.”

JUUL agreed to a nearly $32 million settlement last year with Colorado, that included new requirements that restrict how JUUL can advertise to Coloradans. The money will go to prevention and cessation, Weiser said. “They (JUUL) have now been held accountable, but unfortunately so many people are hooked and are using this product that is harmful to public health.”

The view from industry and national experts

Juul did not respond to CPR’s requests for comment before deadline.

Altria, formerly known as Philip Morris, invested $13 billion for a 35 percent stake in Juul in 2018. But the tobacco giant dumped it earlier this year and bought NJOY Holdings, which makes vaping products that have been granted permission by the FDA to market in the U.S. Altria referred questions for this story back to Juul.

R.J. Reynolds, which makes another popular brand, Vuse, said in a statement: “We steer clear of youth enticing flavors, such as bubble gum and cotton candy, providing a stark juxtaposition to illicit disposable vapor products.”

Other big vape companies, like Esco Bar, Elf Bar, Breeze Smoke and Puff Bar didn’t get back to us before the deadline.

“If we lived in an ideal world, adults would reach the age of 24 without ever having experimented with adult substances. In reality, young adults experiment,” said Greg Conley, director of legislative & external affairs with American Vapor Manufacturers. “This predates the advent of nicotine vaping.”

Joe Miklosi, a consultant to the Rocky Mountain Smoke-Free Alliance, a trade group for Colorado vape shops, said those stores at least are not driving the trend.

“We keep demographic data in our 125 stores. Our average age (of customers) is 42,” he said.

He said vape shops sell products to help adult smokers quit, with lower levels of nicotine than big companies like Juul. Miklosi said he’s talked to thousands of consumers, including, “people in their 80s who said, ‘Wow, I can hike in the mountains again. I stopped smoking cigarettes after 30 years because I switched to vaping products.’ ”

But longtime tobacco researcher Stanton Glantz said the Colorado data appears to disprove that notion.

The 18-24 age group leads all age groups in use, and use gradually dropped with each age group to the 65 and older demographic, which shows just 1 percent using e-cigarettes.

The data are “completely inconsistent with the argument that most e-cigarette use is adult smokers trying to use them to quit,” said Glantz, the now-retired director of the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California San Francisco.

Thanks to Juul, and companies that copied its technology, smooth flavors and marketing, “the kids are getting addicted younger and faster,” he said, then back when traditional cigarettes ruled the tobacco market.

Other national experts also called the numbers eye-opening.

“That's an astounding increase in just two years,” said Delaney Ruston, MD, the filmmaker of The Screenagers’ Movies, which explores social media, drugs, and youth mental health.

Research has shown nicotine is highly rewarding to the brains of young people. So “it's not surprising that many of them start in high school for social reasons, for all sorts of reasons,” said Ruston, whose latest film is “Screenagers Under the Influence: Addressing Vaping, Drugs, and Alcohol in the Digital Age. “And many of them now, we’re seeing this, have continued to college and beyond.”

There are long-term health implications for this population and of the broader trend. If you look at neuroimaging studies, “We are finding that the teen brain is very sensitive to the effects of substances like nicotine, that you don't need it as much to get addicted when in your teens,” said Suchitra Krishnan-Sarin, professor of psychiatry at the Yale University School of Medicine.

She said much more study is needed and underway. By introducing nicotine at a young age, does that change the brain’s neurochemistry which could make it easier to get addicted to multiple substances, said Krishnan-Sarin, whose research focuses on substance use behaviors in adults and adolescents.

G’s story: It’s cool at first, but no so much later

“Getting hooked was almost like, for me at least, irrespective of flavor, of enjoyment, of experience, pleasure post using nicotine,” said G Kumar, a recent CU graduate. “It was like, ‘the cool people are doing it. I'm going to do it.’”

G is 24, a rock climber who likes music and writing and uses they/them pronouns. G started as a college freshman. Once they got into it, the Suorin brand was the go-to, and peach was their favorite flavor.

“The process of going to a vape store and seeing all of these flavors and all of these choices is definitely, it's fun,” G said.

Products that came after JUUL, like disposable vapes, would have more than a thousand puffs in them.

“I'd go through, let's say, 1,200 puffs in a week,” G said.

Eventually, it became a crutch. Like losing a cell phone, a missing vape pen would set off a mad scramble.

“It needs to be right next to my head when I fall asleep at night and then in the morning I have to thrash through the sheets and pick it up and find it,” they said.

Often G got sick and also caught COVID and vaped through all of it, but that was not what made them decide to quit. More than anything it was “knowing the amount of trash (from used-up vape devices) that I was accumulating and the amount of money I was spending.”

G did end up quitting.

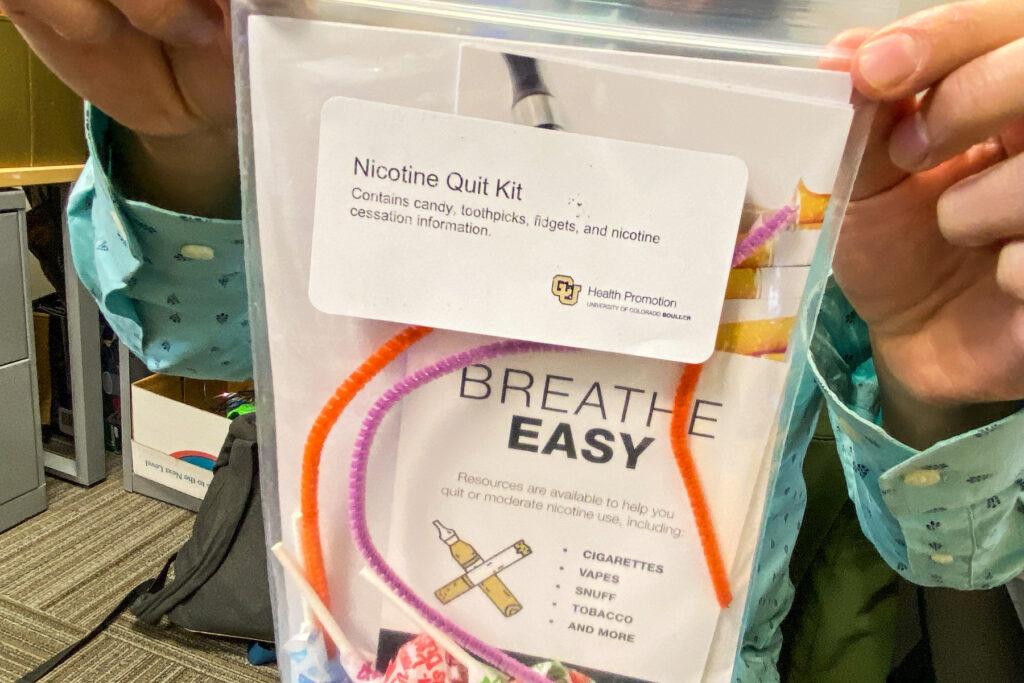

A package of cessation literature and tools to quit in a plastic bag from CU’s Health Promotion program proved useful. It included two boxes of awful-tasting eucalyptus-flavored toothpicks.

“The fact that I could just gnaw on toothpicks for weeks on end was I think what kept me sane,” G said.

It took a while and a lot of willpower to overcome the intense psychological craving, something many in G’s generation know all too well.

Read more stories from the 'Hooked' series:

- How the tobacco industry made it cool to smoke in Colorado’s communities of color

- For those who have fought big tobacco, lobbyist’s presence on Denver Health board is ‘a contradiction’

- In Pueblo, where 60% of high school students report vaping, efforts to curb youth tobacco use are getting creative

- The unlikely affiliation between universal pre-K and nicotine taxes is a story of politics and tobacco money

- Tobacco and vaping rates are falling but products are still easy for teens to get their hands on

- Lawyer on Denver Health board says he’s stopped lobbying for tobacco giant Altria after getting a call to resign