“You feel like you belong somewhere.”

That’s what Althea Brown misses most about home in Guyana.

Now living in Aurora, the 41-year-old recipe-developing food blogger turned cookbook author has replicated the feeling of belonging by cooking the recipes she made growing up.

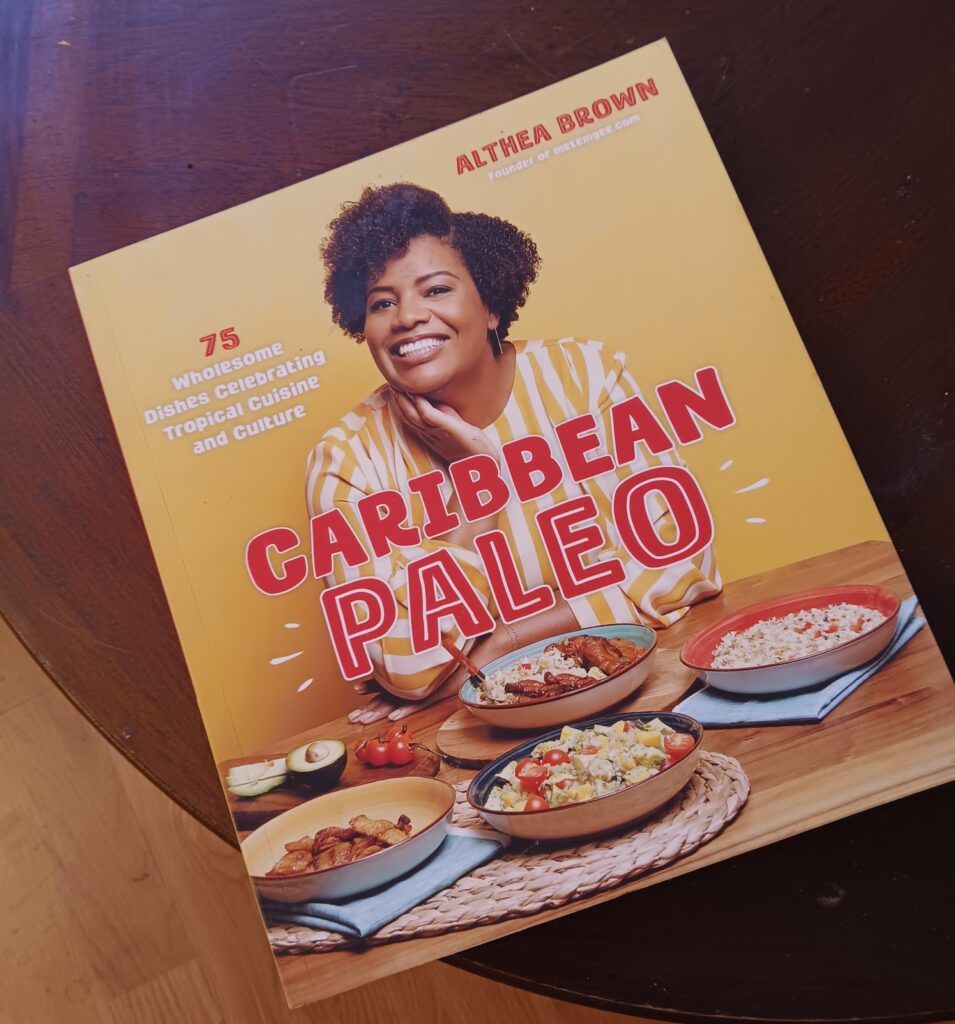

She’s created a blog where she styles and shoots photos of her breads, curries and other meals. That recently led to a reader-requested cookbook, “Caribbean Paleo: 75 Wholesome Dishes Celebrating Tropical Cuisine and Culture,” published last year.

Her decision to focus on food began when she was a child, cooking with her mom and both grandmothers – in fact, it’s to, “My Late Granny Inez and My Late Grandmother Evelyn,” that she dedicates the 167-page book.

“I was always in the kitchen, I think from seven or eight,” said Brown during a recent interview in her sleek gray kitchen. “Being there with my mom as she did it. And then she would start to say to me, ‘do this step’ or ‘do that step.’ And by the time I was 11, then I was in the kitchen doing it.”

Jovial, welcoming and speaking with a slight accent that turns some of her t’s to d’s, tells her personal story while doing a cooking demonstration. It begins with her growing up in Guyana as the middle of seven children, listening to soca music and eating curry with her hands.

The story lands at where she now finds herself: in the middle of her busy life. Often, she is in her dining room, cluttered with screens, lights, props, computers and other cookbooks. The counters in the neighboring kitchen are full of bowls of pre-chopped veggies and cilantro.

On a typical day, the stay-at-home married mom of three creates new recipes. Then she posts the recipes – along with pictures she styles and takes herself – on her blog.

“I love, love, love it,” she says of preparing food for others. “It brings me so much joy to share it with other people and to just make it, going through all the steps.”

Her steps are a dance of fluidity. Moving from cabinet to drawer to sink to kitchen island, she knows well how far to step in one direction to land where she needs to be. She gets a demo started that will result in pumpkin and potato curry served with roti. Her manner in the kitchen is instructive and fun when grinding spices for a masala – a mix of spices. Today, it will be cumin, coriander, curry and garlic.

'This book should look and feel like me'

She often cooks for guests – some who come to her home, some she meets virtually on her food blog Metemgee. It was the regular posting on her site that led her followers to request she put together a cookbook.

“My followers have been asking me for a long time to write a book. ‘Can you write a book? Can you write a book?’”

When she took on the challenge, she wanted it to be as Althea Brown-centric as possible, with fresh material.

“I started saying, ‘Well, if I’m going to write a book, I’m going to just not post this on my blog. I’m going to keep these recipes.’ And I had a little notebook that’s somewhere in that chaos,” she said, pointing to the dining room clutter. “This book should look and feel like me ... and that’s how this whole Caribbean Paleo book was born.”

The book does look and feel like her, as she is both Caribbean and Paleo. The Caribbean part first: She’s from Guyana, a country of just under a million people on South America’s North Atlantic coast, that is, according to Brown, a Caribbean nation, regardless of location.

“We have our native Guyanese people, Amerindians, we have Afro-Guyanese who are descendants of enslaved Africans. We have Indo-Guyanese who are descendants of Indian people that come for indentured servitude. Those two groups, Afro- and Indo-Guyanese, make up the largest population of Guyanese people. And so those foods influence what our foods look like. So you have a lot of fusion things happening ... and I think that’s what makes us a little bit unique: that our food is fusion without it really being fusion.”

Guyanese culture, she explains, has a lot in common with Jamaican and Bajan cultures.

“We listen to soca music, we listen to reggae, we eat tea and curry, we eat jerk chicken … so the food, the culture, all the things we do is just Caribbean, so I’m a Caribbean person. Yes, I happen to be from a country that is in South America, but that’s just geography!”

She explains it like this:

“We are very much connected to other Caribbean countries that had a history of British colonization. . . . and so in the way that they shaped these colonies with indentured servitude and slavery and everything else that happened, the same kind of people ended up in Guyana as they did in those other Caribbean islands.”

Her husband is a Guyanese man who’d been a childhood friend; his family had immigrated to Texas. They reconnected and later got married and moved together to Colorado because of his work in the oil and gas industry. Soon they became a family of five, and to keep busy as her kids started entering school, she decided to try food blogging.

Going paleo

Around 2016, she noticed eating white flour and sugar made her feel less than great, and as she eliminated those and other foods from her diet, what remained were mainly clean ingredients that didn’t drag her down. Adapting a paleo diet of mainly unprocessed foods became her routine.

The Mayo Clinic describes the paleo diet to include, “fruits, vegetables, lean meats, fish, eggs, nuts and seeds,” foods easily accessible in the Paleolithic Era. When she realized that the paleo diet worked for her, she knew that would be the best way to represent herself both from a cultural standpoint and a dietary perspective.

“I realized that there were so many other people who were just like me, who were not just Caribbean people, but other people who wanted to try a different cuisine ... I can include traditional things that fit into paleo.”

Finding ways to convert traditional recipes to paleo has been easier than she thought. Often, it’s a question of substituting wheat flour with a different type of flour.

“A lot of our dishes are gluten-free and paleo, like the root vegetables, the stews at the root of them,” she said. “The things that I had to actually convert were all the things that used flour, right? The roti, the sweet breads, the pastries, those things I had to sort of think out of the box for.”

Brown has figured out a way to make the bread using boiled cassava and other substitutions. She’ll look at a recipe and imagine how to paleo-ize it.

“I’ll kind of read it and say, like, ‘OK, I have a general idea of what it is,’ and then as I start cooking, I might kind of tweak it a little and put something else that might be where I think it should go.”

She’s not hardcore about following all the rules all the time.

“When I eat paleo, I feel my best self. I always say I’m ‘paleo-ish’ because I’m also a craving person, and there’s some foods that actually don’t make me sick that are not paleo. And so I allow myself to eat those in smaller portions that I would have before I became paleo.”

Finding pride and culture in roti-making

Brown takes pride in her roti-making.

Similar to naan and paratha in Indian cuisine and fry bread in Native American cuisine, roti is a Guyanese/Caribbean interpretation of a round saucer of bread from which food can also be served. For simplicity’s sake, she demonstrates making roti using white flour. To get the dough as flaky as possible, she rolls it into a ball, kneads it a bit, then turns it into a cone, tucking in thin strips of dough that later made flakes.

“The thing that makes it really layered is that we will clap it at the end – that’s the one thing that … other cultures don’t really do, so I feel like that the thing that we do that separates our culture a little bit from other Caribbean countries.”

When asked what it means to “clap” a roti, she explains:

“Imagine that the roti is an accordion and you toss it in the air and then you actually clap your hands with it in every step. So it kind of gets all the layers to break apart.”

She tosses a partially cooked roti up in the air, frisbee-style, and then as it descends, she anticipates the timing so she can clap her hands on either side of the dough – a move that shatters the dough into even more flakes.

Then, it only takes about a minute or two to fry it. It comes out warm and, of course, flaky – a perfect substitute for the cutlery she does not lay out. Instead, she urges the use of a pull of bread as a scoop to pick up the food, and as a surface to eat it from – something that links back to the history of colonization, which in turn is what links Guyana to the Caribbean.

“In Guyana, because we were a colony and because people put a lot of emphasis on eating the way the Queen ate or speaking the Queen’s English at home,” she said. “You are taught to have these mannerisms; that if you go outside of your house, you can actually eat with a knife and fork and you know how to do that in society. But also we ate a lot of meals with a spoon, and we also ate a lot of meals with our hands because you would be ripping roti and eating and enjoying it that way.”

It makes her feel close to her grandmother. Brown recalls watching her “smooshing rice up and feeding it to herself with her hands.”

It’s moments like that that she gets that feeling of belonging, no matter where she is – in her Caribbean home country of Guyana, or in suburban Aurora with her husband and children – even if it’s not the way the queen would do it.

“When I make certain dishes that remind me of her, I’ll just sit with a bowl and eat it with my hands because it makes me feel closer to her.”

Cooking up connection

Finding a sense of belonging through a Caribbean community of choice in Colorado has not been so easy. Aurora, with a population of nearly 400,000 is the most diverse place to live in Colorado, but the state doesn’t have many Guyanese.

“I’ve not been able to find a specifically Guyanese community, but I found a Caribbean community.”

Before the pandemic, a group of people of Caribbean descent would meet regularly to do service projects such as sending school supplies to a selected Caribbean community. They also had an annual picnic before disbanding because of the pandemic.

“That felt really nice to just be connected with people that shared a similar culture.”

Her food blog has helped with that.

“Once in a while I’ll find a follower who will say, ‘You’re in Colorado ... I’m also in Colorado. And then I’m like, ‘OK, I’m going to message you; just call me. We’re in the same place. We should be friends. Or at least get together and see what it feels like.”

Sitting down to eat her food, a reporter and audio producer, now hungry with hands covered in flour after trying to clap the roti, dig in eagerly. The layers of the roti create extra surface area for the curry to cover. Combining the tangy sweetness of the curry with the warm multidimensional bread is an experience that, consumed with her stories, tastes of belonging.