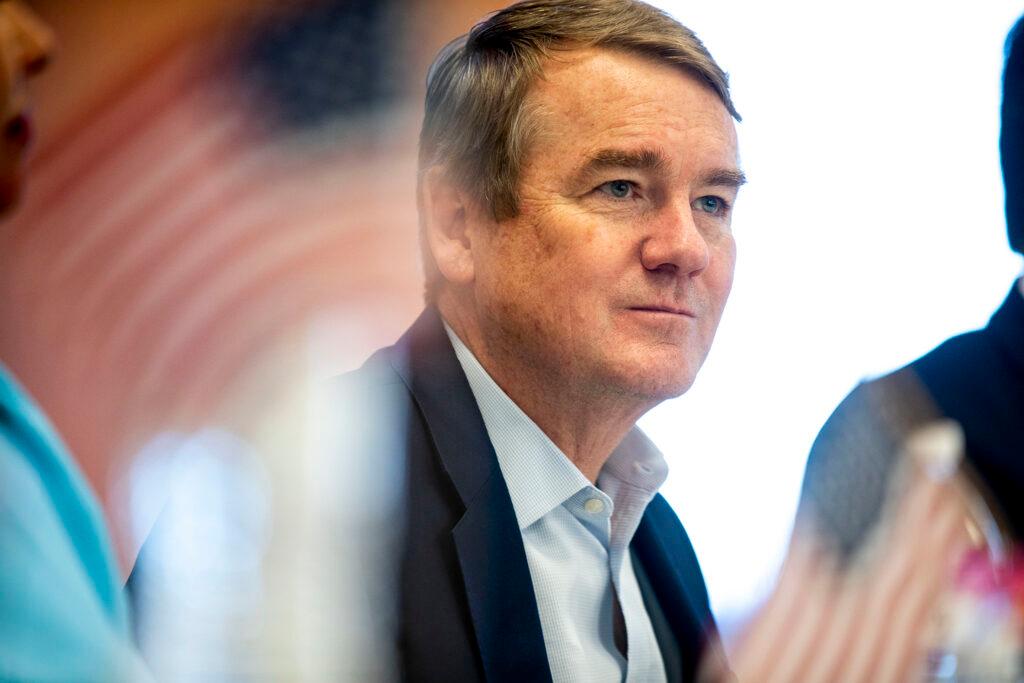

At the end of July, Sen. Michael Bennet was in remote Gunnison County, outside of cellphone range, trying to build support for a public lands bill.

What he didn’t know was that the White House was trying to get a hold of him.

“A staff person from my office in Grand Junction had to drive all the way from Grand Junction to the campsite,” Bennet recalled months later.

Bennet hopped in the car and headed toward Crested Butte, where he knew he’d get a signal. With his cellphone in his hand, he kept looking for those telltale bars to appear.

But by the time he finally got service, it was no longer a mystery what the call was about. “The news had broken that the decision had been made,” Bennet said.

The decision he was talking about: Colorado Springs would remain the home of U.S. Space Command, permanently.

President Joe Biden had reversed a decision made by his predecessor to move the command from Colorado to Alabama.

Still, Bennet rang the White House. “They said, ‘We were just calling to let you know.’ And I said, ‘Oh, thank you. Well, I appreciate the effort.’ And then I got back in my car and drove back to the campsite.”

Anyone paying attention to Colorado news even casually over the past few years has likely heard something about Space Command headquarters and the years-long tussle between Colorado Springs and Huntsville, Alabama, over which city would finally claim it as their own.

When it looked like the state would lose the command, Colorado’s entire political leadership agreed to set their differences aside and work together for a common goal: keeping it in Colorado Springs.

Colorado celebrates victory in the national battle for Space Command, but the future is uncertain

Colorado and Alabama have been fighting for the U.S. military base for space missions. But political games have made the issue about far more than national security.

By Caitlyn Kim and Dan Boyce

Aside from the bragging rights of housing another combatant command (Colorado Springs is already the home to NorthCom), Space Command could bring the region a long-term economic boost of over $1 billion, as well as attract and keep more companies interested in space national security. Colorado already has a strong aerospace sector. Space Command has the potential to boost it even further and help insulate it from downturns.

To understand the role Colorado’s political leaders played in convincing President Biden to keep the command in their state, CPR News spoke with many of the people who led the charge. They revealed a saga of intense lobbying, unlikely cooperation and pivotal conversations. CPR also reached out to Air Force officials, past and present, who were involved in the decision. All declined to comment.

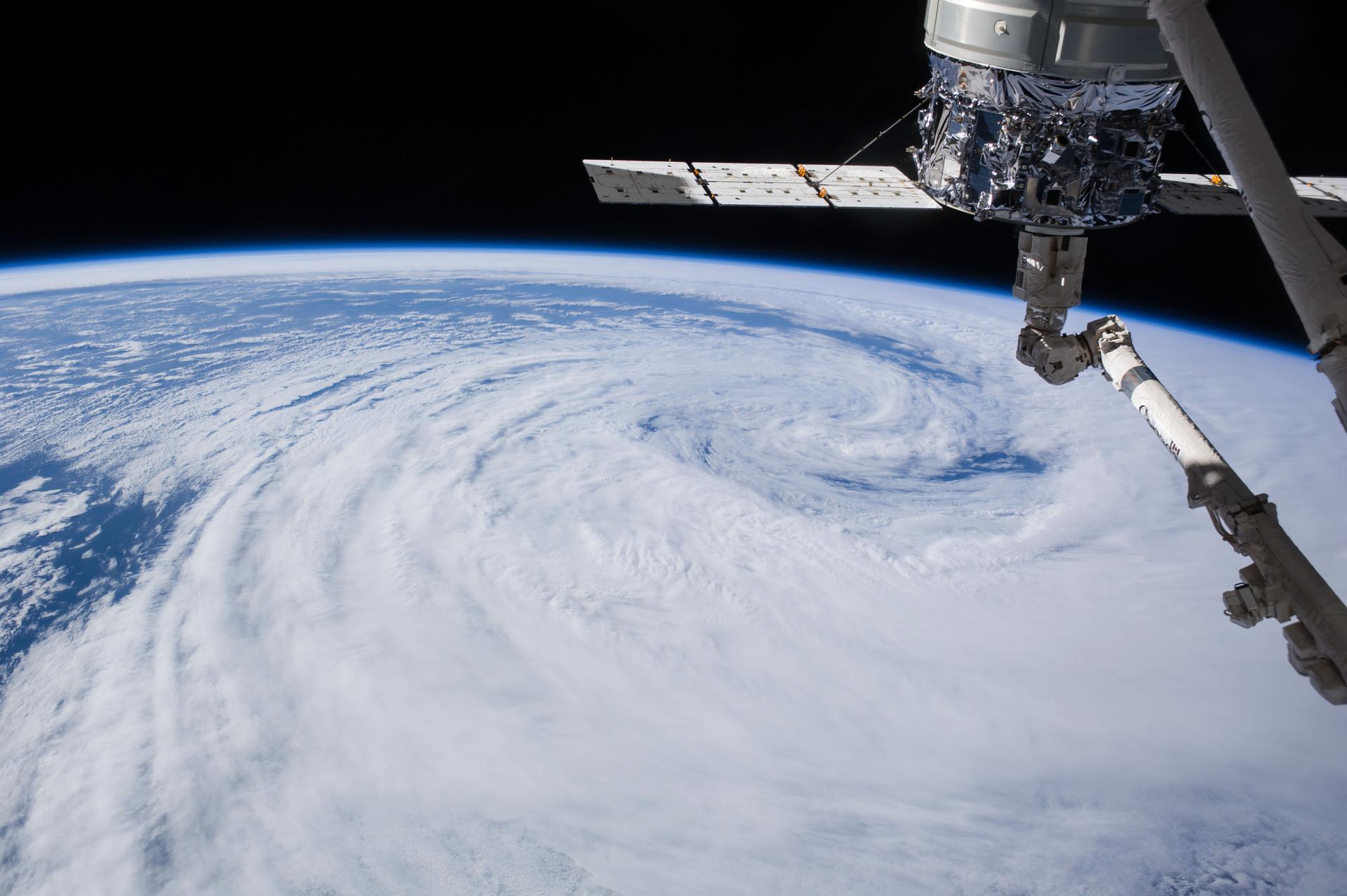

A brief history of Space Command.

The first thing to know about Space Command is that it is not Space Force. Space Force is the newest branch of the military, charged with managing and protecting U.S. space-based assets like satellites.

Space Command is a combatant command, basically a place where all branches of the American military come together to orchestrate — and coordinate — space-based missions.

The second thing to know is that U.S. Space Command has come and gone over the decades. It was first established at Colorado Springs’ Peterson Air Force Base in 1985, with the goal of countering the USSR’s high tech advances.

After the September 11th attacks, though, the military shifted its focus away from Cold War rivals and towards counterterrorism. The work of Space Command was divvied up and moved elsewhere and the command was officially mothballed in 2002.

But in recent years, with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan winding down and threats from large powers like China and Russia amping up, the Department of Defense has again started to focus on space and cyber warfare capabilities.

And so, in a Rose Garden ceremony presided over by then-President Donald Trump on Aug. 29, 2019, Space Command was officially reborn.

“It’s a big deal. As the newest combatant command, SPACECOM will defend America’s vital interests in space — the next warfighting domain. And I think that’s pretty obvious to everybody: It’s all about space.”

President Donald Trump, Aug. 29, 2019

To start with, the newly revived command would return to its old home at Peterson. But the Air Force insisted that was only temporary; it quickly launched a search for a permanent base.

Still, Colorado’s federal lawmakers hoped being named the provisional headquarters would tip things in their favor in the long term.

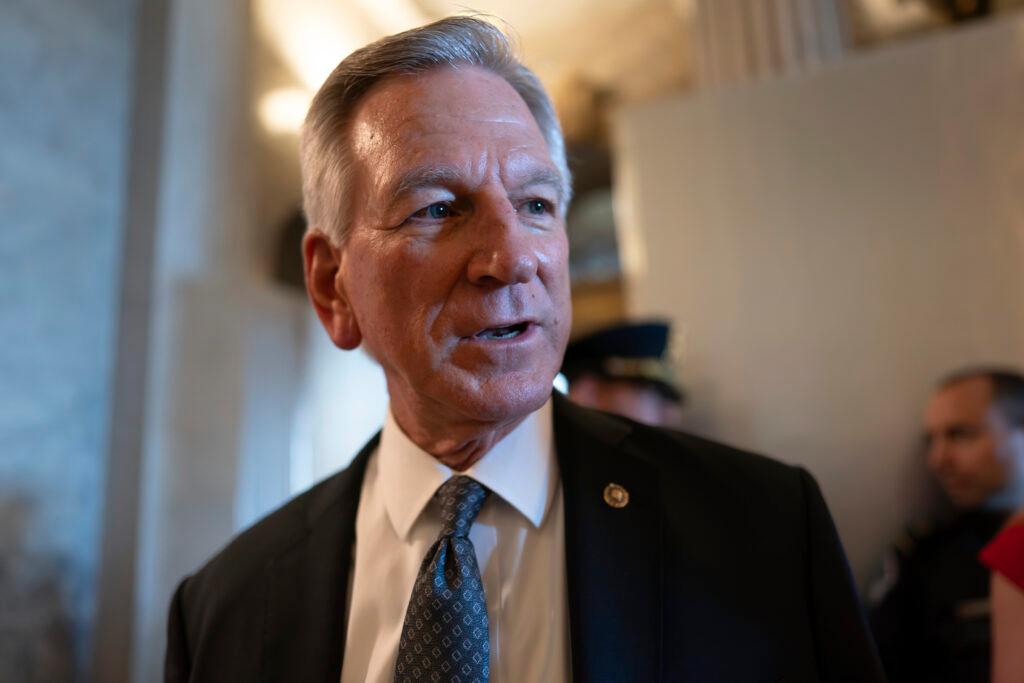

“We knew it would be a good step because it would help Colorado Springs solidify its position,” recalled El Paso County Congressman Doug Lamborn.

A few months before the Rose Garden ceremony, the Air Force released its finalists list, which definitely leaned toward Colorado. Four of the state’s bases, including Peterson, were on the list, along with Redstone Arsenal in Alabama and Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

That announcement generated a lot of heat; other states with lots of space infrastructure, like Florida, felt they hadn’t been given a fair shake. The Air Force agreed in March 2020 to start again. Not only would it conduct a nationwide search, but it agreed to change how to select the final base.

Under the new process, cities could apply to host the headquarters. And officials would give weight to a much broader range of criteria: not just military factors but also a community’s quality of life and cost of living.

“I think it was understandable politically,” said former Colorado Springs Mayor John Suthers. “A lot of politicians were putting pressure on the administration.”

When it came to this new process, Suthers’ administration wasn’t taking anything for granted.

“We didn't want to have any kind of presupposed notions that just because we were the temporary or the provisional base that would definitely continue over,” recalled Dawn Conley, Suther’s military advisor and part of the team working on the Springs’ bid. “So we tried to look at it kind of really from a blank slate.”

Colorado leaders knew they faced some fierce competition from one city in particular: Huntsville, Alabama, home of Redstone Arsenal.

Like Peterson, Redstone made the final lists twice, under both the original criteria and the new process. Huntsville has a long history in missile defense and aerospace. Nicknamed Rocket City, it’s also home to NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center.

On top of that, the region scored well on cost of living and quality of life.

For their part, Alabama officials worked to make sure military leaders and the Trump administration heard all the reasons that Space Command’s future should lie in their state.

As early as 2018, Alabama Rep. Mo Brooks was pitching Huntsville, which is in his district, for the permanent headquarters. “Redstone has a lot to offer,” he said during a subcommittee hearing titled “Space Situational Awareness,” that included Gen. John Hyten, who was head of Strategic Command at the time, before rattling off a long list of the city’s space-related activities.

“We’re already doing things many people can only fathom,” then-Madison County Commissioner Dale Strong told local Alabama media in May 2019 (Strong went on to succeed Brooks in Congress). “The heavy concentration of engineers, our workforce that’s here, the University of Alabama in Huntsville — this is the optimal place.”

As states jockey for Space Command's permanent home, Trump dangles his decision.

Just like their counterparts in Alabama, Colorado’s political leadership tried every avenue they could think of to help the state’s chances.

Gov. Jared Polis took his pitch right to the top.

“The conversation with President Trump (was) certainly one of the more unusual ones, in the sense that it's hard to get the guy's attention,” said Polis.

Polis spoke with Trump aboard Air Force One in February 2020 after the then president landed in Colorado Springs for a political rally.

“We met privately for quite a while, probably 20, 30 minutes,” he recalled. But getting Trump to focus on the topic took some effort. “Probably 80 percent of the time was him talking non-sequiturs about different things. But absolutely, I had the time to make the case on Space Command and probably spent five minutes that he got to listen to on that.”

That evening, Trump teased the issue to the crowd in the Broadmoor World Arena.

“I will be making a big decision for the Space Force, as to where it’s going to be located,” he told the cheering crowd. “And I know you want it.”

Trump even mentioned Polis’s visit. “He showed up because they wanted to see if they could get it. That’s OK, that’s alright. And we are going to be making that decision,” he promised, “when we make that decision.”

Polis wanted to keep the basing decision above the political fray, but from the start that felt impossible.

“It's hard to do that with someone like President Trump. He views everything, I think, through sort of what some might call a political view. But it's also kind of a view of what's best for him, what's best for Donald Trump, and so you have to kind of couch your arguments along those lines.”

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis

Suthers also spoke with Trump as the president got off of Air Force One. Standing with a military delegation on the tarmac, the mayor made the case that keeping the command in Colorado Springs would benefit both taxpayers and national security.

As Suthers remembers it, ”The president looks at one of the (generals)...and says, ‘Is this where it belongs?’ And the four-star general says, ‘Absolutely,’ points to the ground, says, ‘This is where it belongs.’”

But that wasn’t the end of the conversation. Suthers said Trump asked if he was a Republican and what the mayor thought his chances were in Colorado for the upcoming election.

“Being the diplomat that I am, I didn't say, ‘No chance in hell, Mr. President,’” Suthers said. “I said, ‘Uncertain.’ And he seemed a little bit perturbed by that and he said, ‘Well, I think I'm going to wait until after the election to make this decision. I want to see how it comes out.’”

Trump went on to lose Colorado by 13 points. Alabama, in contrast, went 25 points in his favor.

Suthers said you didn’t have to be a genius to read the tea leaves; “I was pretty certain on election night we were in bad shape.”

Trump announces his preferred state, but the battle for Space Command headquarters continues.

In the chaotic months after the election, as Trump grasped at legal straws to stay in power and his supporters stormed the U.S. Capitol, it seemed possible he might end his term without announcing a decision on Space Command.

But on Jan. 13, 2021, with seven days left in office, news broke that the Trump administration had named Huntsville the preferred location for the permanent headquarters.

“I couldn’t be more pleased to learn that Alabama will be the new home to the United States Space Command!” Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey said in her announcement on Twitter. “Our state has long provided exceptional support for our military and their families as well as a rich and storied history when it comes to space exploration.”

Air Force Secretary Barbara Barrett called to give Lamborn a heads up.

“She tried to justify it on the grounds of the reconsideration of different factors,” Lamborn said. “She didn't sound very convincing to me. I'm not sure she was convinced herself, but she was very loyal and wouldn't second-guess Donald Trump, the president who had appointed her in the first place.”

Sen. Bennet was shocked by the decision; not just the news itself, but the timing.

“I think pretty quickly our heads were spinning because of Jan. 6, getting ready for Jan. 20 (Inauguration Day) and making sure that the incoming administration understood that President Trump had made this in the waning days,” he said.

And despite the announcement, Colorado’s officials were far from done fighting for the command.

Colorado leaders demand a review of the Space Command decision.

The first thing Colorado leaders had to figure out was what their options actually were.

“How do you appeal?” recalled Sen. John Hickenlooper. He had seen how Washington operates as mayor and governor, but at the time was only days into his new job in Congress. “We weren't going to have much time and we had to do everything we could.”

It is a point of pride for Conley how quickly and completely the state and its congressional delegation dug in to fight the decision. Fridays, their meeting days, were nicknamed “Space Command Fridays,” as representatives from each office gathered to plan their next steps.

At the table were Republican representatives who had voted not to certify the election and Democrats who worked on both of Trump’s impeachments, not to mention a Democratic senator, Hickenlooper, who’d just unseated a GOP incumbent. But in this particular effort, partisan differences didn’t seem to matter.

“You sit where we are now and you look back and that was one of the most impactful decisions, was we want the whole state to be united in this and use all of our relationships and networks to bring as much horsepower as possible,” said Hickenlooper.

The state had a limited window in which to sway the White House into reconsidering; the final basing decision would come after an environmental assessment of Redstone, the preferred location, Peterson, and the other finalist sites.

The delegation swiftly sent a letter to the White House and the new president. Their ask: conduct a thorough review of the basing decision to see if it was in the military’s best interest, or if political considerations played a role.

“One thing we had to do is get our hands on the information that they used — purportedly, with quotation marks around it — to make the decision,” said Lamborn.

Lamborn got the congressional watchdog, the Government Accountability Office, to start a review of the basing selection.

The state also wanted the Defense Department’s inspector general to look into it, but setting that in motion would take work, including help from the right people on the right committees. In that area, Colorado was at a distinct disadvantage.

At the time, Alabama had numerous members sitting on the committees with direct oversight of the matter. Colorado only had two.

So to push forward, Colorado lawmakers worked with allies from other states to help them make their case.

In the House, Tennessee Rep. Jim Cooper, then-chair of the Strategic Forces subcommittee, and California Rep. John Garamendi, then-chair of the Readiness subcommittee, both asked for an inspector general investigation.

On the Senate’s Armed Services Committee, Nebraska’s Deb Fischer, a Republican, and Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire, a Democrat, became vocal advocates for questioning the basing decision, according to Hickenlooper.

Some of these lawmakers represented communities that had also tried for Space Command and were equally dismayed to see it go to Huntsville. Others were just concerned that the process seemed untransparent and vulnerable to political influence.

“The broader coalition you can create, the more strength you have in making your case. So we enlisted our friends, our allies, folks that understand space issues deeply. People that are dedicated to the national security of the United States, and we were able to do that effectively.”

Colorado Rep. Jason Crow, who served on Armed Services at the time

The watchdog reports come out, but do nothing to end the fight.

Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama.

It took over a year, but both reports finally came out in the late spring of 2022. And if Colorado’s advocates were hoping for a smoking gun that proved the decision was made for political reasons, they were disappointed.

The reports showed Alabama had indeed come out on top under the Air Force’s more holistic basing criteria.

“Both reviews were positive,” said Alabama Sen. Tommy Tuberville in a triumphant video statement, pointing out, “the process Air Force officials used to select Huntsville complied with the law and policy. And it was reasonable in identifying Huntsville as the preferred location for headquarters.”

Tuberville also took a jab at Colorado’s long-running, and very public, effort to get the decision overturned.

“We purposefully stayed out of the public discourse on this for the past 16 months. It’s not good for our military and it doesn’t change the facts. Instead, we’ve worked quietly behind the scenes to make sure the process was allowed to play out as it should. But now my message to my colleagues is simple: it’s time to fully embrace the Air Force’s decision and move forward together.”

Alabama Sen. Tommy Tuberville

Colorado, though, saw no reason to give up. Its officials focused on something else the reports found — that while Huntsville triumphed in the selection process, the process itself had significant flaws.

“If you take both reports together, there are some pretty significant indictments of the process,” said Bennet.

He complained that each factor in the basing decision was treated the same — so the quality of local schools and the availability of parking carried as much weight as special access communications and the availability of an appropriately skilled workforce.

And there was one factor, in particular, that Colorado lawmakers felt wasn’t given its due consideration.

“The Air Force's own IG report concluded in the end that the Air Force had paid insufficient attention to the readiness question,” Bennet said.

Colorado’s advocates latched on to the issue of full operational capability, or FOC — basically, how quickly the command could ramp up to full strength at any given location — as their best selling point.

“The two reports said that when you took FOC, readiness, into consideration, Colorado Springs went to the top of the list, but (the Air Force) ignored that because they were looking at things like school districts and housing costs and utilities and things like that,” said Lamborn.

The final IG report came with big sections blacked out, but an unredacted draft obtained by the news site Breaking Defense gave the Colorado coalition another talking point. It confirmed that while Huntsville scored higher on the selection criteria, top generals had preferred the Springs, and said as much in their decision document to President Trump.

Colorado leaders court the Biden administration, hoping to reverse Trump's decision.

As the wait for a final decision dragged on and on, Colorado’s advocates pushed this issue with the administration every way they could.

“My staff reached out to Air Force and Space Force staff at least three times a month, pretty much on a weekly basis, for two and a half years,” recalled Lamborn, “constantly getting the newest information.”

With a Democratic president in office, the pressure was on Colorado’s Democratic lawmakers to lead the charge for Colorado Springs.

“We certainly had better access in the Biden administration than in the Trump administration,” said Crow.

He was able to have a lengthy discussion with President Biden on Air Force One in early 2022, arguing that keeping the command in Colorado was in the best interest of national security. He also pigeonholed Biden’s secretary of defense and the head of the Air Force.

“I approached it from every angle. I talked to anybody and everybody who would listen, and even sometimes if they didn't want to listen. I would corner folks in the Pentagon and make the case."

Colorado Rep. Jason Crow

Bennet also had a couple of one-on-one conversations with Biden. In October 2022, the two rode together to Camp Hale, between Eagle and Leadville. Biden was preparing to make the site a national monument.

Bennet recalled arguing that “it would take a long time for it to be set up in Alabama, that it would cost a lot of money to be set up in Alabama, and that the generals had agreed that…where it should stay was Colorado, and that Donald Trump overruled them and made a political decision.”

Losing Space Command arguably carried risks for politicians like Bennet. During his 2022 reelection campaign, Bennet’s challenger, Republican Joe O’Dea, argued he wasn’t doing enough.

O’Dea said Bennet should hold up nominations and block bills until he got a guarantee that the headquarters would remain in Colorado. Bennet countered that politics needed to stay out of the decision.

Looking back later, Bennet reflected, “I think the last thing we wanted to do in the early days of this was politicize a decision that had been made politically by Donald Trump.”

As Hickenlooper explained, this was especially important because the Air Force itself was leery about appearing to make a political move if it reversed course.

“We had Secretary Kendall in this office saying, well, we've done these investigations and we've looked at both the investigations and reviews that we've done. We don't see any evidence of political nature being involved in the president's overriding the decision and judgment of the generals,” said Hickenlooper.

The Coloradans felt they had one strong piece of evidence, thanks to Trump himself.

In late August 2021, the former president called in to an Alabama radio talk show. Toward the end of his appearance, the conversation turned to the headquarters.

“(Space Command) said they were looking for a home and I single-handedly said, ‘Let’s go to Alabama.’ They wanted it. I said, ‘Let’s go to Alabama. I love Alabama,’” Trump said on the Rick and Bubba Show.

Conley said it was one of her happiest days of the Space Command saga, hearing Trump say those words and verifying what Coloradans had long thought.

“I literally went into the mayor's office and was kind of doing a little happy dance because it was like, did you hear that? Oh my gosh. Trump finally admitted it, that he had done this and it was a political move, and so we were pretty happy."

Dawn Conley, Suthers' military advisor

But for the Air Force to get on board with reversing the decision, it was going to take more than one off-the-cuff comment.

As the final basing announcement drags on, tensions rise between Colorado and Alabama.

As they worked to convince Air Force leaders of Trump’s motives, the Colorado delegation returned to the former president’s 2020 campaign stop in the state, the questions he’d asked Suthers outside Air Force One.

Suthers penned a letter to Pentagon leaders recounting the conversation and the strong sense it left with him that this would be a political decision.

Around this time, Hickenlooper, frustrated that Colorado’s arguments apparently weren’t being heard inside the Pentagon, started reaching out to Washington Post columnist David Ignatius to point out “all these things that we pieced together to see whether he thought that was worthy (of a story),” Hickenlooper said.

In the course of digging into the issue, Ignatius got a hold of Suthers’ letter. He wrote about it in a March 23, 2023, column. But that wasn’t what got the Coloradans most excited; in the same article he reported that, according to a source in the administration, the White House was going to reverse course on the basing decision.

“We felt pretty good about that,” said Suthers. “I really felt like that was a turning point.”

Needless to say, that news also got the attention of Alabama lawmakers. Rep. Mike Rogers, chair of the House Armed Services committee, and his colleague Rep. Strong, promptly announced a committee investigation into why it was taking so long for the Air Force to announce its permanent basing decision.

As the situation dragged on, things only got more political. Abortion became an issue; Alabama lawmakers accused Biden of wanting to keep Space Command in Colorado because of its favorable abortion laws. At the same time, Tuberville was holding up hundreds of routine military promotions over a Pentagon abortion policy. When Coloradans argued with him about that, Space Command inevitably got dragged into it.

While the Alabama delegation worried the headquarters might be about to slip away from them, the Coloradans were increasingly concerned all their work might come to nothing.

“There were a few times when I was worried that there was too much else going on at the White House,” Bennet recalled. “That the inertia that had set in at the Air Force couldn't be overcome.”

Biden makes the long-awaited announcement: He's decided on a permanent home for Space Command.

On June 1, 2023, there was another fateful presidential visit to Colorado.

President Biden traveled to Colorado Springs to give the commencement address at the U.S. Air Force Academy. Once again, Suthers found himself in a line of dignitaries waiting to chat with a president. This time around, he had Bennet by his side.

“Bennet, being a savvy guy, says, ‘Hey, look, I'll have a little chitchat about his trip to Japan. And then I'll say…Mayor Suthers has been working incredibly hard on this Space Command issue,’” Suthers recalled.

But even before the mayor could make the pitch, Suthers said Biden chimed in, saying he was very, very, very aware of the issue, but that a decision still needed a bit more time.

Biden went on to say exactly what Suthers wanted to hear, that the White House was focused on “where can we get up and running the fastest and the most effective.”

“We were incredibly heartened,” said Suthers. “In fact, I felt very confident walking away from that… And lo and behold… almost two months later, that's the decision that's made.”

On July 31, 2023, the White House announced Peterson Space Force Base would be the permanent home of Space Command headquarters.

“This decision is in the best interest of our national security and reflects the president’s commitment to ensuring peak readiness in the space domain over the next decade,” said National Security Council spokesperson Adrienne Watson.

Old home, new home, red home, blue home.

Biden’s decision immediately reversed the playing field. Now it was Colorado that was celebrating, and Alabama’s leaders who were vowing not to give up.

This time, it was a bipartisan group of lawmakers from a Republican state arguing that a Democratic president acted unilaterally to benefit a state that supports him.

“Unfortunately, the Biden administration has chosen to play politics with our national security,” said Rep. Rogers at a committee hearing on the decision in September.

During the hearing he was backed up by two other Alabama members on the committee: Strong and Democratic Rep. Terri Sewell.

Strong kept pointing out that Huntsville came in first based on the criteria, while Colorado Springs ranked fifth.

“We’ve made a political decision over a competency decision. I know this administration strives for equity, strives to be fair and this is simply unfair,” said Sewell.

Lamborn, as the only Coloradan on the committee, made the lone case for the state.

“I was kind of the kicking toy,” Lamborn said ruefully. And he was. Many of the other Republicans on the committee gave their speaking time to the Alabamians or seemed to side with them.

Lamborn used his time to point out all the reasons, like readiness and cost, for why the command should remain in Colorado. And he confirmed that the witnesses, which included Air Force Secretary Kendall, supported the administration's decision.

“President Biden exercised his authority and discretion as Commander in Chief and Chief Executive to make the final decision to locate the permanent headquarters of USSPACECOM in Colorado. I fully support the president’s decision.” Kendall told the panel.

He added basing decisions involved balancing different, and often competing factors. For Kendall, the top two were cost and operational risk. “All six locations were reasonable alternatives, but Huntsville was lower cost, while remaining in Colorado posed the lowest operational risk under any circumstances.”

The dilemma this situation illustrates is clear: Whether the command moves to Alabama or stays in Colorado Springs, once allegations of politics enter such a high stakes process, can a final decision ever be free of that taint?

Bennet thinks yes.

“I think it's really important to have a president who makes those basing decisions based on national security. And I would much prefer to have a president who makes those decisions based on national security, not based on politics. So for me, that's in a way a big win too, because I think we were able to reassert the way these decisions should be made."

Colorado U.S. Sen. Michael Bennet

Alabama, of course, does not see it that way. Its members have now asked for their own reports from the Pentagon’s inspector general and the GAO on the Biden decision. And they plan to use their committee perches to fight the plan to keep the headquarters in Colorado Springs, including withholding construction funds until their reports are out.

To make all this even more complicated, the whole thing has dragged on into another presidential election year.

“Now, the 800-pound elephant in the room is what if Donald Trump gets reelected president of the United States?” Suthers mused. “I think he would probably be inclined to say, ‘Oh, my decision was the right one and I'm going to reverse the Biden administration decision.’”

Some in the Alabama delegation are hoping so.

Still, Suthers said the longer Space Command remains in Colorado, the stronger the case becomes for keeping it here permanently, especially now that it’s fully operational, a milestone the command hit in mid-December.

Polis agrees that time is now on the state’s side.

“It might not be over yet, but there's only minutes on the clock here. And we just need to make sure that the longer this becomes a reality, that we defend it aggressively based on the merits, avoid distractions, and continue to support our national defense, including Space Command.”

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis

Moving now, advocates can argue, would make the country vulnerable, with little to be gained in the future.

Story by Caitlyn Kim and Dan Boyce

Edited by Megan Verlee

Produced by Lauren Antonoff Hart