The way the state funds schools hasn't changed in 30 years. Now there is a new proposal to overhaul the state's education funding formula. The legislature-appointed a bipartisan Public School Finance Task Force released its recommendations to more adequately and equitably divvy up money to educate Colorado's 880,000 K-12 students.

“This is a real step forward,” said task force chair Chuck Carpenter, chief financial officer for Denver Public Schools. “To have waited 30 years to do this and to now have this thorough and well-researched recommendation, I think it would be important for the legislature to take it very seriously.”

The 60-page report aims to make school funding “simpler, less regressive, more adequate, understandable, transparent, equitable and student-centered.” Task force members also sent a clear message that implementing an updated more equitable formula will take money.

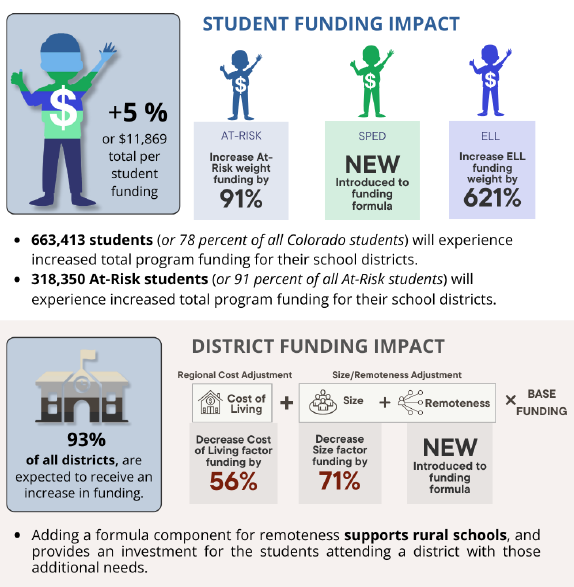

The report says to make the new formula work, Colorado’s K-12 schools need another $474 million, raising total per student funding five percent. It would be up to lawmakers to figure out where that money would come from. The 17 task force members say the proposal generally prioritizes higher-needs students, lower property wealth districts, and small rural districts.

Colorado has districts with 90,000 students and districts with 50 students. Putting together a mathematical formula that addresses the unique needs of all districts was a tall order.

“I see this report as a milestone in Colorado’s story of school funding — finding a way to create an equitable and adequate system of education that meets the needs of a diversity of students in a diversity of locations,” said Lisa Weil, task force member and executive director of the nonprofit group Great Education Colorado.

The state spends roughly between $1,500 and $2,800 per student below the national average and in the past, whenever education groups rallied behind a proposal to raise money for schools, other groups, seeing the formula as inequitable, opposed it. The new proposal bridges the philosophical divide on many of the core recommendations.

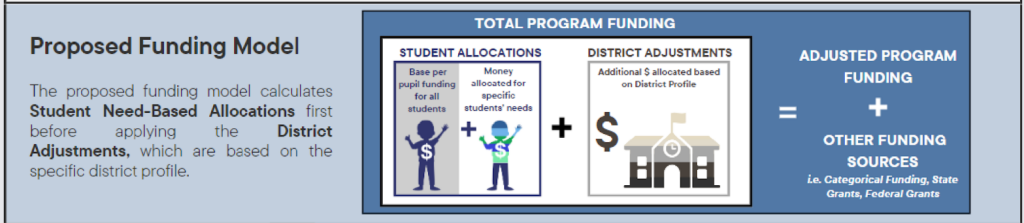

Colorado’s current funding model takes the number of students in a district and adjusts based on school district size, cost of living, personnel costs and extra student needs such as whether a pupil is at risk. The recommendations, which would impact 178 school districts, shift the funding focus more to the qualities of students rather than district factors like size.

“The proposed formula is simple, equitable, and focuses on what should be our top priority, which is students,” said Brenda Dickhoner, president and CEO of Ready Colorado, a conservative education reform group and member of the task force.

The task force recommended phasing in changes to the new formula within at least four years. It asks lawmakers to take into consideration results from what will be the state’s first-ever study on the actual costs of educating a student in Colorado.

“How does Yuma differ from Kim or Brighton?” said Weil. “What are the cost pressures that are the same, what are different?”

In the final report, 93 percent of districts would see a funding boost. A district like Denver would see $90 million more next year. Widefield, $3 million more. Garfield, $8 million more. Jefferson County, half a million.

Without extra money from the legislature, 13 districts would lose money including Aspen ($5 million), Lewis-Palmer 38 ($3 million), and Douglas County ($26 million.) But the task force recommends maintaining the legislature’s “hold harmless” support so no districts lose money. That adds $64 million to the $474 million cost.

“We're not trying to say that any district is overfunded right now,” said Carpenter. “I don't think anyone believes that. But I don't think anyone would lose if the legislature took up our recommendations.”

Why has it been so hard to update the funding formula?

For years, lawmakers have tried and failed to update the School Finance Act of 1994 because it would create school districts “winners and losers.” Some called the formula’s complexity a ‘quadratic equation.’ In 2018, 171 superintendents came up with a “student-centered” funding formula, but that died. Voters rejected other statewide proposals to raise funding.

With each passing year, pressure mounted to update the formula - and boost funding. Over the past 14 years, state lawmakers have diverted $10 billion from public schools to other parts of the state budget. At times, Colorado’s education spending has ranked below two of the poorest states in the nation: Mississippi and Alabama. In boom years, anything the state raised over TABOR spending caps was refunded to taxpayers.

Funding is slowly recovering – but even if Gov. Jared Polis’ K-12 budget proposal passes this year, Colorado schools will still be funded at 1989 levels when adjusted for inflation.

But there’s another reason pressure grew for a formula update: Today’s students and schools have changed dramatically since the formula was originally created in 1994.

Why are school needs different than they were 30 years ago?

Classrooms are no longer a single teacher with 30 kids; it’s a team of adults because student needs and academic expectations are much higher. For example, schools provide costlier career and technical education and concurrent college enrollment.

Brain science and the science of how children learn have also accelerated rapidly. Educators can now pinpoint where a child is in their reading development and intervene – whether for struggling readers or gifted readers, said task force member Leslie Nichols, superintendent of the Gunnison Watershed School District.

“We can do that when we're funded better and have the professionals with the expertise who can be brought to our schools,” she said.

Research and examining other states underscored that at-risk students and students living in poverty require many more resources to educate. Demands for mental health support in schools have also increased significantly.

Nichols’s district is the size of Delaware and Rhode Island combined so transportation costs are higher. Expenses mount for calling in HVAC specialists from Grand Junction to service a building, or to bring in audiologists from the Front Range.

School safety costs have risen dramatically, with schools requiring security personnel, secure entries, and – a huge expense for her district, doors that lock from the inside.

“It's hundreds of thousands of dollars to upgrade that simple hardware across this district of 2,000 students,” she said.

The bipartisan task force of public education experts and practitioners spent four months digging into data, researching best practices in other states to make the final recommendations. Weil said she thought coming up with something everyone agreed upon would be impossible.

“The school finance formula is incredibly complicated,” said Weil. “We had really rich conversations unlike any that I have been a part of in 20 years of doing this work ... We didn't agree on everything. There are a few minority reports. But it really does advance the ball.”

The proposed formula

It starts with adjustments to the per-pupil calculation, adding weight for at-risk students, English language learners, and students with disabilities. Adjustments in the formula for school districts have shifted to the end of the formula.

For districts, the cost of living factor would be capped at 10 percent and would fluctuate. The size factor benefit would only apply to districts with fewer than 1,027 students instead of 6,500 students. But there would be a new remote district factor benefit.

Current system has an inequitable impact on districts, but some still worry about long-term impacts

Currently, the cost of living factor drives money towards high property value districts like Aspen that already tend to generate more money from local property taxes. While that factor helps them attract teachers, it also ends up taking away money from low-property-wealth districts that have a hard time raising local property taxes.

“The state subsidizing Aspen and Telluride when Pueblo gets $7,000 less in per pupil revenue than Aspen doesn't actually make a ton of sense to me,” said Dickhoner. Pueblo School District 60 has 85 percent of its students classified at-risk while Aspen has six percent, she said.

The proposed new formula lessens that cost of living factor but adds a factor to help small, remote districts. It’s estimated that the new plan would benefit rural districts by $200 million.

The Gunnison Watershed school district stands to gain $3.5 million because it is rural and remote. But superintendent Nichols worries that long-term taking away the size factor for districts with more than 1,027 students doesn’t adequately recognize economies of scale.

“The expenses are just much higher when you're smaller,” she said. She’s hopeful, however, adequacy studies can put a hard number on what the cost differences are.

It is unclear when the report, which had a Jan. 31 deadline, will be presented to the legislature.