Ignacio has been in the U.S. since August, and his favorite classes are algebra and a class that helps him with his English. Those are not easy classes.

“My hardest class is algebra,” he said. The required math is hard enough when you speak English. It’s nearly impossible when you’re just learning the language.

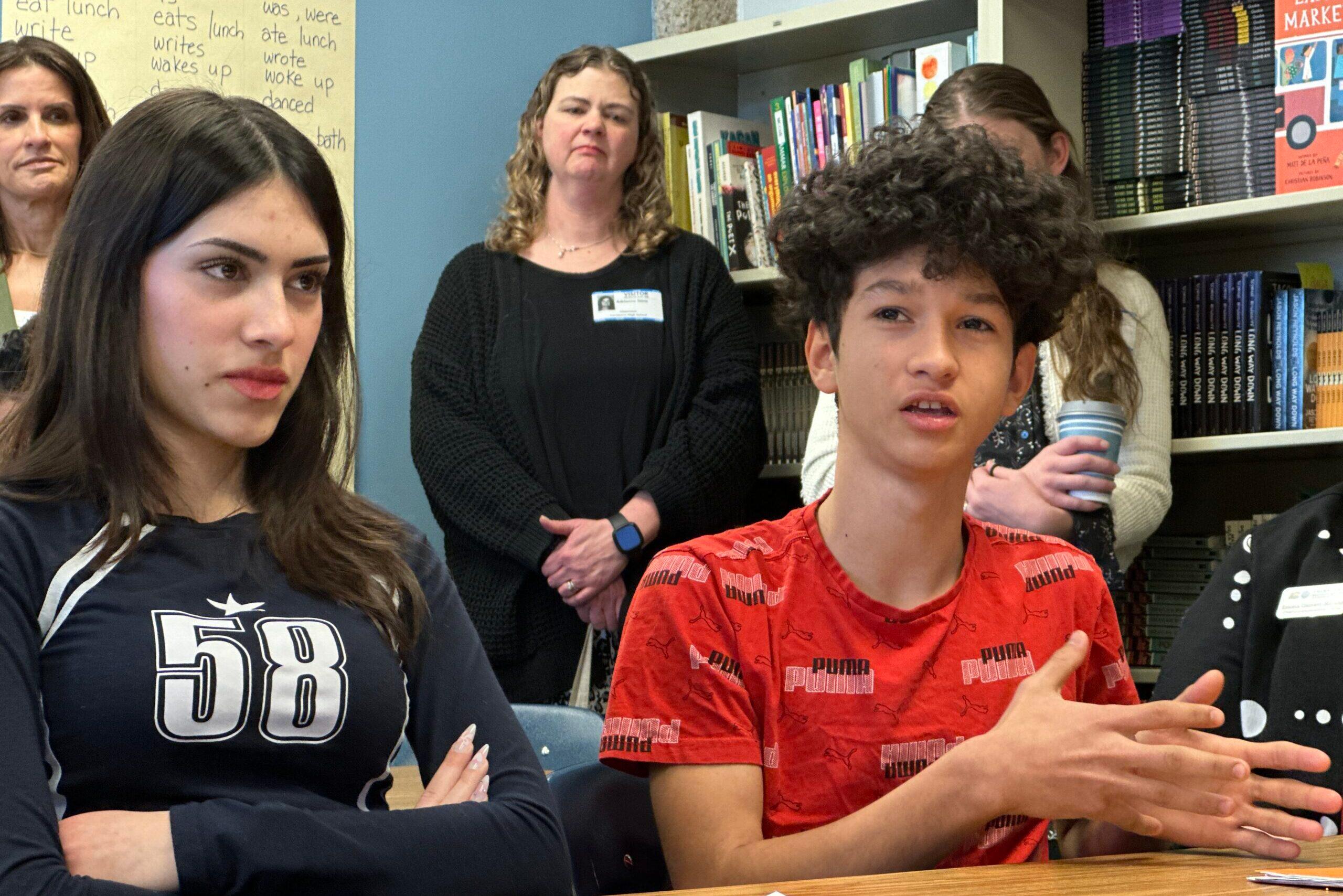

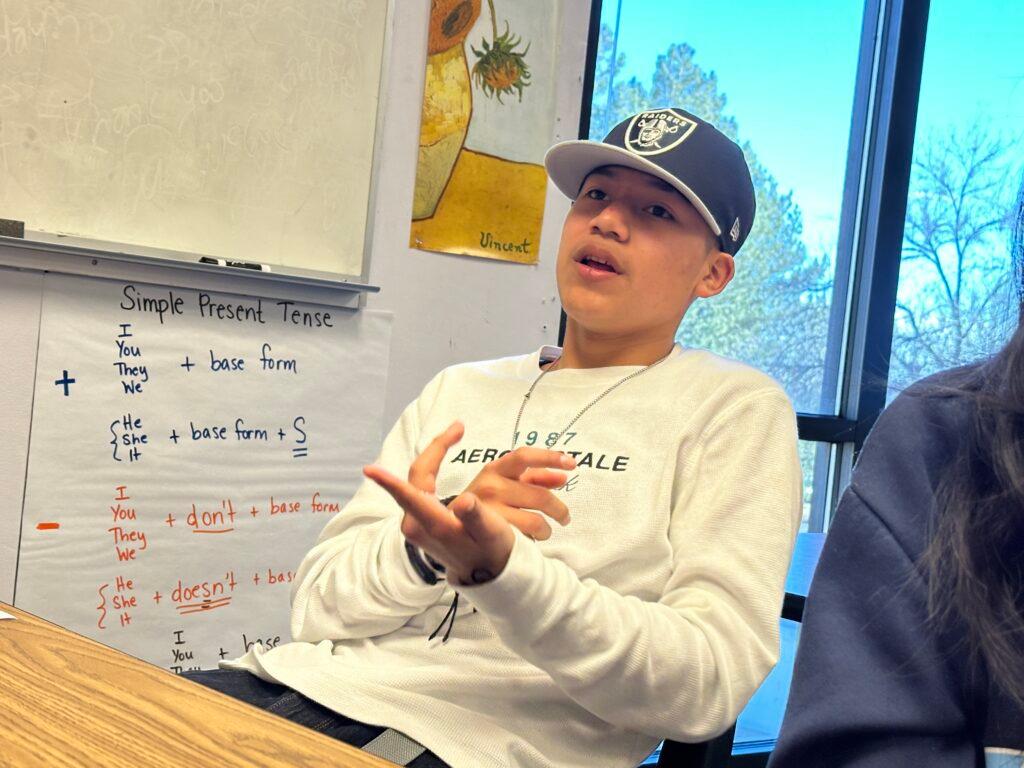

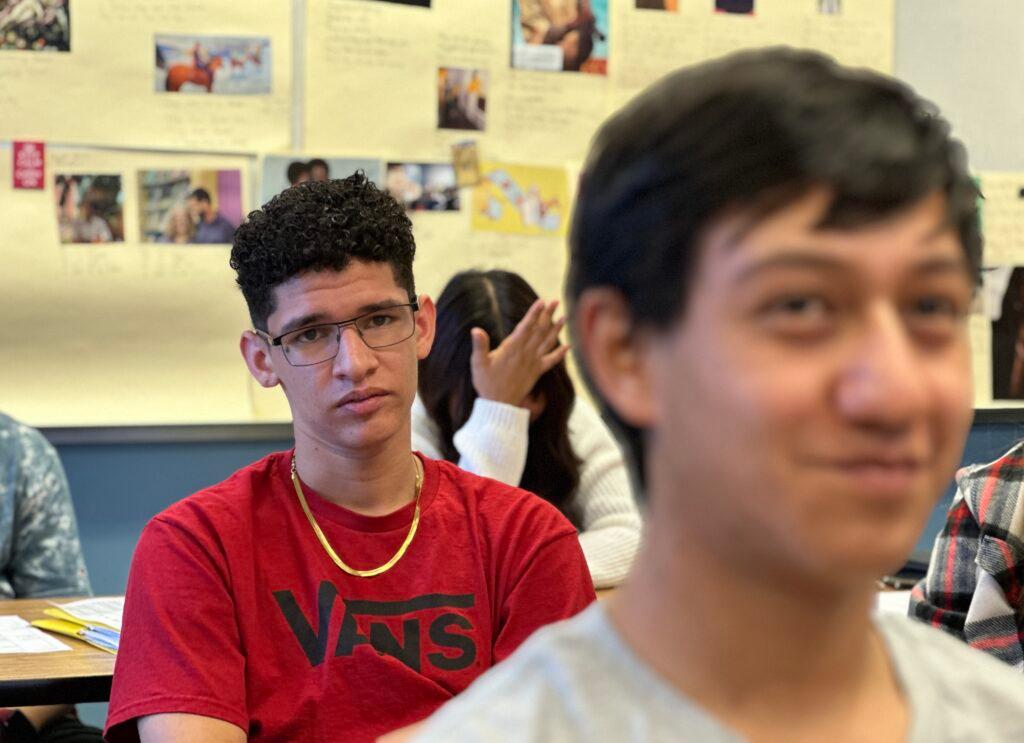

The freshman told this to school administrators who lined the four walls of his classroom at Centaurus High School in Lafayette.

The English language development specialists from across the state listened to Ignacio and his classmates and learned about the school’s process for integrating newcomers.

How to serve an influx of thousands of new immigrant students who have arrived in Colorado is top of mind for administrators from about 20 school districts. They’ve formed a “newcomers cohort" to get guidance and share strategies to educate students who mainly only speak Spanish.

In the fall, several metro districts asked the Colorado Department of Education for support and plans to meet the surge of student needs.

“This work is tough … this is work that wasn’t there when you set your budgets,” Boulder Valley School District Superintendent Rob Anderson told the administrators. “This is work that has gotten exponentially harder, exponentially more complicated. It’s not just like figuring out curriculum and instruction, it is the strain on all of the other supports in a school when you have an influx of students coming in as newcomers.”

But Anderson, like the more than 50 educators who toured Boulder Valley high schools Thursday, is trying to design a blueprint to best welcome and educate the influx of new students.

“This challenge that we’re facing isn’t going away and it will take the best of us with our best ideas working together to figure out the solutions to make sure we’re supporting our kids and our families.”

While Denver has received 3,000 new immigrants since the summer, districts across the state are feeling the increase

Boulder has enrolled 600 newcomers this past year. Centaurus alone has welcomed 35 this school year.

Teachers popped into high gear — putting together a more targeted plan. There is a full intake session with families to understand the kids’ backgrounds and give them a tour of the school before they start classes. Schedules that include two periods of learning English along with other content classes. Most of the kids said they struggle with classes like history, government, and math, which are all in English. But they love all the support they’re getting here.

“Even though (the teachers) don’t speak Spanish, they always try to put Spanish words on the PowerPoint presentations to help us,” said one girl in Spanish.

Every week the English language teachers send out tips to all the teachers in the school. They’re plastered on hallway walls to help them know how to help the new students, instead of saying “I don’t know,” said Centaurus principal Dan Ryan.

“I see teachers using this so the teachers are really on board,” he said. “They need instruction, they need tips and they need help and our team (English language development) has been pushing that out so that’s been huge.”

The administrators and educators are intrigued by a class Centaurus has developed where kids get support on the language or concepts they might see in a history class before they get to that class. That takes more planning time and English language teachers working closely with other teachers.

“If there was one thing we could do to make your lives easier or better here as students in the Boulder Valley school district what would that be?” Anderson asked the students.

At first, they’re quiet. They said everything was good and that it was safe and there was lots of support.

English language development teacher Lauren Jaeger has a suggestion. “Candy? Doughnuts?”

“My grades!” one boy jokes.

Finally, Alvaro from Guatemala said he wants to study mechanics so he can help his uncle with his business.

“I’m learning little by little like how to change oil, but I want to study that in school to learn more,” he said in Spanish.

Centaurus doesn’t offer career and technical classes like mechanics. But a district official told the students they’ll find a way to get any student to the district’s tech center to take classes. During the yearlong “newcomer status,” the students get free rides to school on a bus or Uber.

The administrators take notes on the services Centaurus provides so that they may be able to implement them in their home districts. The school has community liaisons, informal Latino parent groups, wellness rooms, and a new offering – Cafecito — where kids can meet for group therapy and other mental health support. They get backpacks and school supplies, free tickets to football games and homecoming dances.

There has been a big effort to get kids involved in extracurriculars like intramural soccer or weightlifting. Jaeger said the school has an open-door policy where classrooms are open for lunch and homework help.

“There’s usually anywhere from five to 20 students during that time,” she said. “It’s just a place to hang out, a place to get help with algebra or whatever it might be and it’s a nice place to build community.”

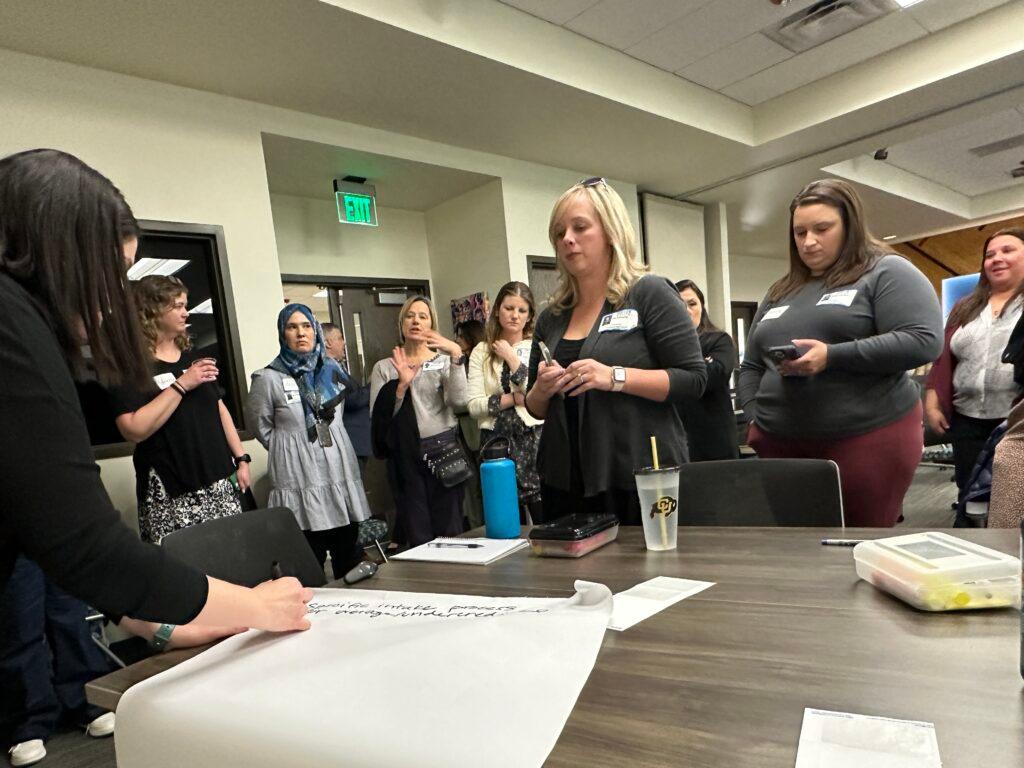

In the afternoon at district headquarters, the educators scribble ideas on flip charts about what they can bring back to their own districts

Some things that Boulder Valley School District does will be challenging to other districts. Some said their districts don’t have the transportation to get kids to other activities. Others said their greatest challenge is space with some educators already taking a regular-sized classroom and splitting them in half, with double the number of kids.

“They're bursting at the seams with the number of students now that they're welcoming into their schools,” said Victory Molina, a professional learning coach with the Colorado Department of Education.

For many years, most districts have had systems in place for homeless students or those who are learning English.

“But those systems are overwhelmed,” she said. “So, what they might be used to, and we plan for and budget for and have staffing for now has just exploded. There's a great need. How do we reconstitute our systems to fit this larger influx of people coming so that we can best serve our families and our kids?”

Adams 12 has received more than 1,000 Afghan refugees in the last couple of years, and this year, mostly from Latin America, 800 newcomers. The district recently opened a newcomer center at Thornton High.

Amanda Clayton, director of culturally and linguistically diverse education, said they tried to accommodate students, even if it’s just making sure they have a desk.

“We don't want to start a wait list as you're only a newcomer once in your life. We want to be able to welcome every single student who chooses that option.”

But she said they need more staff, more materials, and more space — and all of that comes with a price tag.

State officials said they can offer more technical support, are trying to get more state funding, and hope to be able to provide more trauma support.

Though there are strains on the system, the attitude in the room is one of positivity and concentration. These educators said over and over, they want to do what’s best for kids.

Many also like the idea of trying to give to prep educators who teach history, math, and other core subjects with language ahead of time that will help the newcomers. The Sheridan School District’s Denise Lopez said her district used to get one or two new students in a class where a student could help translate.

“Now we’re having five or six, maybe seven in a classroom,” she said. “And so now what do we do if the teacher's not bilingual and or doesn't have experience with maybe differentiating a lesson for those kiddos? So thinking about grouping, what does that look like?”

Teachers are trying to tackle multiple challenges. How do they assess students? What if they are homeless? What if they are supposed to be taking Algebra 1 but are screened at the third-grade level? Can students get English credit for English language classes? What about kids who are older than 18 but short some credits? What if students say they’ve taken biology but don’t have a transcript?

“We have heard that there are kids who lost their transcripts traveling from Venezuela in the jungle, and there is no one back home to be able to produce a transcript,” said the Boulder district’s Kristen Nelson-Steinhoff.

Boulder Valley schools are just starting to experiment with interviews to see whether students who have lost transcripts can get partial credit. The day is filled with sessions to try to answer questions. Everybody’s sharing ideas. Schools have never seen the number of students from other countries on this scale.

During a student panel, many of the kids say their dreams are simply to learn English and to be able to help their families

Others aren’t here with their parents. They may live with an aunt or a cousin and family back home are counting on them.

Anderson, 17, who attends Arapahoe Ridge High, said abuse from his father affected his ability to read and write in Spanish, and he thinks that’s making it hard to learn English. But he said that’s in the past. Today is a new day, he said. His favorite class is art.

“I don't have words to say that I feel proud when a work is done because in the end when it turns out, it doesn't matter if it turns out pretty or if it turns out ugly, well I feel proud because I did it. And each time I learn.”

Ana, 16, from Honduras, loves art too, especially painting. At home, where she loved studying the natural sciences, she remembers spending two to three hours a day just walking to school. Here she walks five minutes to a bus stop.

Ana talks to her parents every day who are back in Honduras, telling them about her day at school.

“They say they're very proud of me because I’m their only daughter who is studying.”

- After 30 years, a new way to fund Colorado’s schools is ready for lawmakers’ eyes

- Colorado child care providers worry new proposal will put them out of business, but applaud rules on animals and potty chairs

- Migrant students in Denver and Aurora becoming a statewide issue to solve

- Colorado educators call for change of a system ‘on the brink of crisis’