For six years straight, Pueblo’s Minnequa Elementary received one of the two lowest ratings on the state’s school report card. Today it’s a green school – the top rating for schools.

It won one of Gov. Jared Polis’ “Bright Spot” awards for math achievement and he named Minnequa in his 2024 State of the State address.

CPR education reporter Jenny Brundin spent the day at the school — one that was for years threatened with closure if test scores didn’t improve. She learned how much planning and hard work it takes to lift a school up.

7 a.m. Principal Katie Harshman arrives at the school

Harshman started at the school in 2011 as a teacher. She said Minnequa, where nearly 90 percent of the 270 students qualify for federal free and reduced-price lunch, had a lot of things going for it. The principal was great. The culture was good.

“The real piece in the problem was turnover," Harshman said. "We had a lot of teachers come and leave and so you could never sustain practices.”

In 2019, Harshman took over as principal. The school was in the red zone and under state order. Improve or close.

“It was scary because I had a year to get this right,” she said.

8 a.m. Harshman leads a community meeting with third, fourth, and fifth graders in the school gym

There are songs, updates, and talk from Harshman to fifth graders about the “big, big misconception around the world that cussing is cool.”

“It has to stop!" Harshman said. "You are my leaders and the little guys are walking by and if they see someone with a Minnequa Hero hoodie on and you’re doing something that’s not the Minnequa way, they are going to follow you because you are a leader!”

There is a big emphasis on building character and kindness at Minnequa. The meeting moves on to happier things. Each teacher names a standout student of the week, and the kids pick nifty prizes like a $5 bill or a fidget toy. At the end of the day, she’ll choose the winner of a hoverboard.

Harshman and her staff didn’t raise the school on their own. The state order names Relay Graduate School of Education, a nonprofit that trains teachers and principals, as a partial manager to help with picking curriculum, assessment training, and coaching. Harshman got a coach. Did a yearlong leadership training with Relay. Intensive weekly meetings and coaching followed. They built a strategic plan.

“When you have purpose and you tie everything back to your purpose, teachers will follow you,” she said. “They believe in you because it's not pulling out from the sky.”

Improving school culture, building community involvement, and raising student achievement. Those three things were their north stars.

8:30 a.m. Harshman flips open her iPad to her “playbook”

The playbook contains her weekly goals: what she wants to see teachers doing in the classroom that week and the coaching steps she’ll take. Sometimes it’s short, quick clinics where all the teachers practice a skill, full professional development sessions, real-time feedback, or weekly data meetings with groups or individual teachers.

This week she’s looking specifically for ways the teacher prompts kids to find the answer on their own, instead of providing the answer.

“We want to be able to unpack the scholars' thinking but we also want to be able to give them enough time to think about what we’re asking them,” Harshman said.

After observing a class, she immediately writes an email to a teacher detailing all the positives she saw and things the teacher might try in the future. Harshman often asks, “What do you need? How can I help you?”

The one thing Harshman really doubled down on is being available and flexible for teachers. Intensive feedback to teachers is a cornerstone of the improvement plan. Being with teachers and students, encouraging and helping is her jam. Harshman is in the classrooms all the time. All day. She didn’t stop once at her desk, spotless except for a stack of books, Angela Duckworth’s “Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance,” notably on the top of the stack.

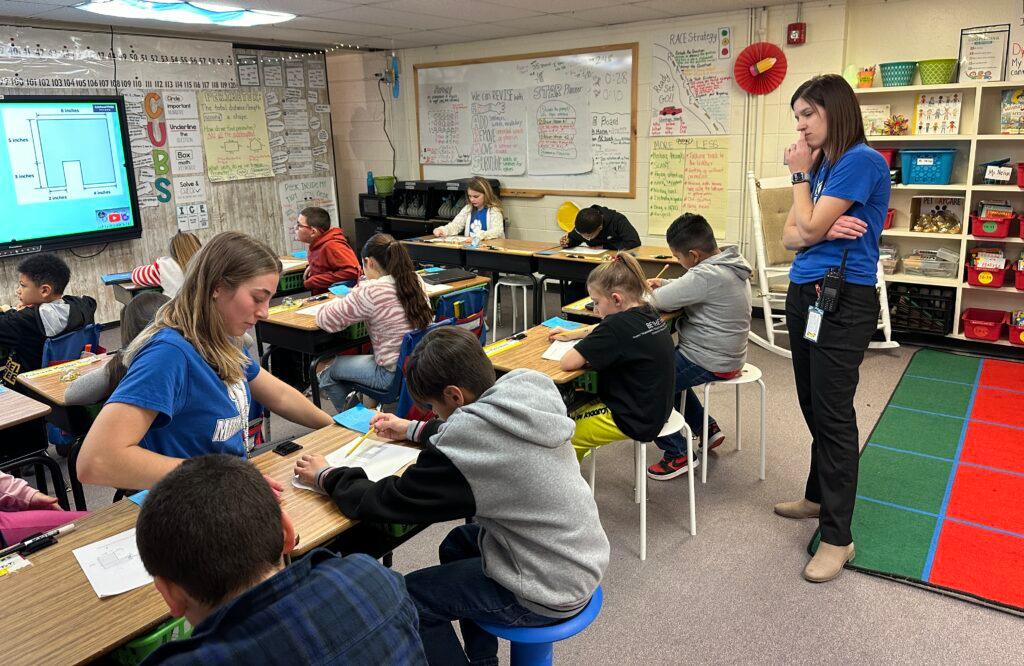

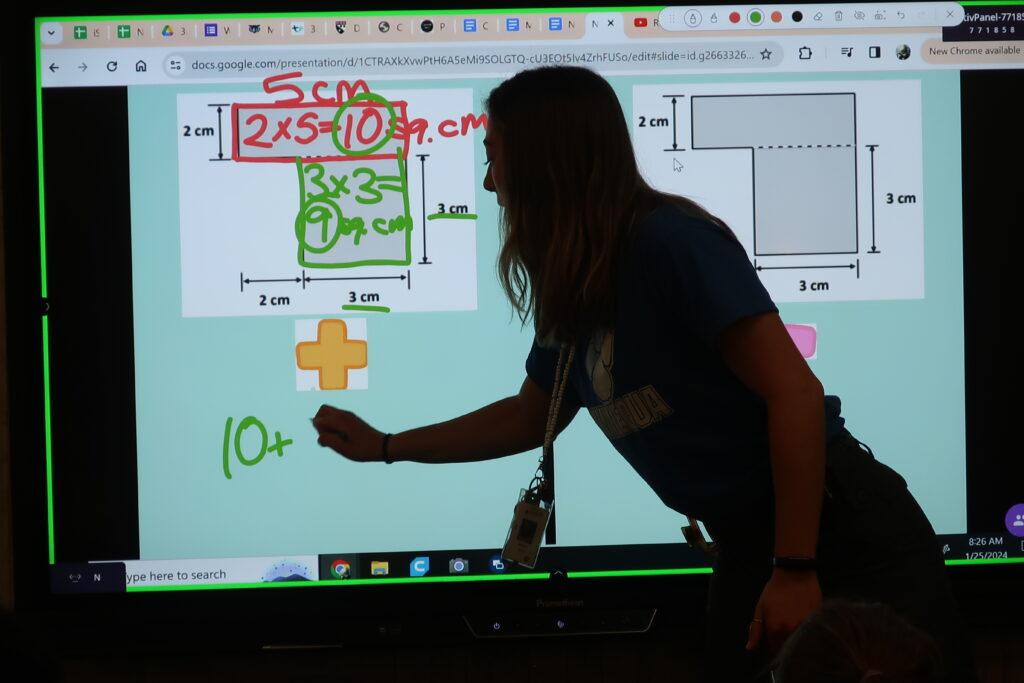

9 a.m. Ms. Nelson’s third-grade math class

“What is area measured in?” asks Nelson.

“Square units!” the third graders shout back.

Nelson is constantly moving. “We call it aggressive monitoring,” she said.

Harshman taught her that.

“She has shown me how to really get into every kid's business for lack of a better word,” Nelson said. “You’re always walking around, you’re naming what you're looking for. So that you can take real-time data of what kids are getting right, what they're getting wrong.”

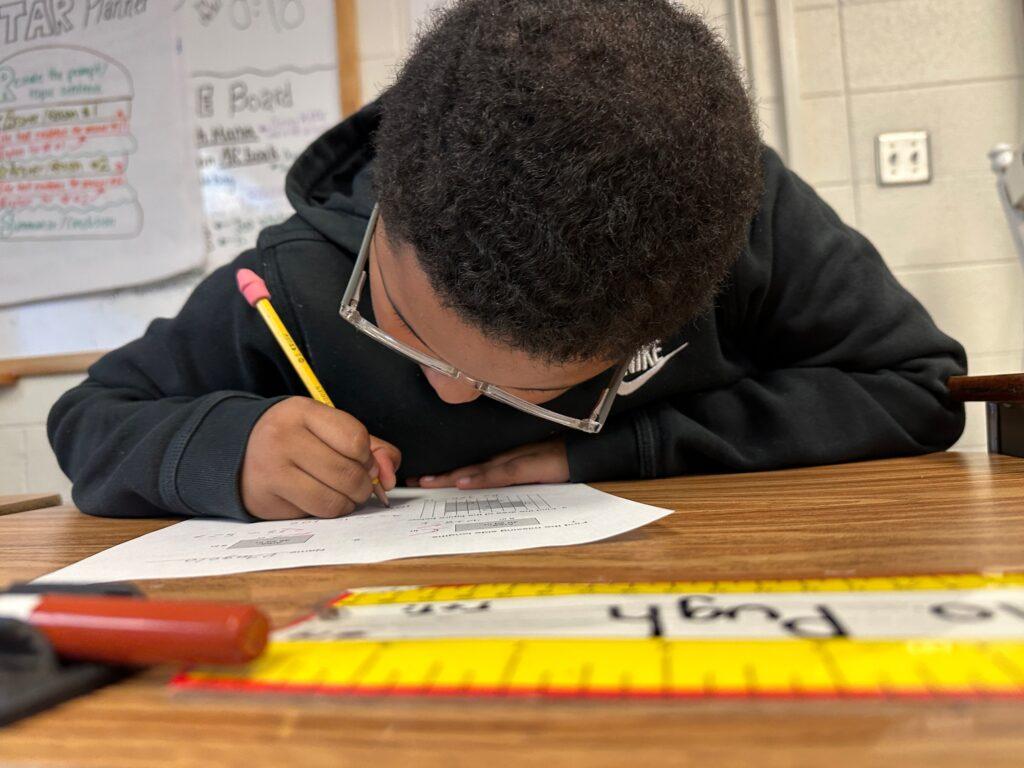

Today is a hard concept. Students are calculating the area of a shaded part in an irregular shape. Sometimes they’re given one piece of a side length and have to figure out the full length before moving on to multiplication to find the area.

“Can you tell me why you multiplied them? What do you think?” Nelson asked. The student hems and haws and finally guesses. Nelson never gives the answer. She’s patient, gently pushing the student to explain what he’s thinking and why.

Some of the kids are stuck and confused. Some are doing subtraction to find side lengths. Some are doing addition. Some are multiplying when they should be adding.

Harshman and Nelson quickly conferred, whispering. Nelson asked Harshman which process she should focus on first. Harshman uses the same strategy they use with the students – explain your thinking.

They develop a plan of attack to get kids going again. Nelson immediately adjusts the lesson. The kids start to get it. They’ve come a long way since their first screening test at the start of the year.

“Oh my gosh, I was asking so much questions to my teacher! What am I going to do here?” exclaims third grader Henlee, who said she likes the energy Nelson puts into her class. “There was division, there was multiplication, and we didn’t know anything about them!”

“At the beginning of the year we had small brains,” adds Eladee. “But now we have big brains.”

The kids appreciate that she uses real-life examples like problems with pizza and water bottles. Or travel questions.

“She’d be like, “How many miles did I fly from South Carolina to the North Pole?” said Eladee. “When we grow up, math is everywhere. It’s like at the store, if this bag of chips is $4 and this chair is $20, and if I have $10 how much more money do I need to buy the chair and the chips.”

Eight percent of Minnequa’s students scored proficient in math in 2019. That number has more than tripled in four years. Along with coaching from Relay, 2Partner Mathematics also helped Minnequa develop strong planning, and lesson delivery, and use data to support instruction.

9:30 a.m. - 11 a.m. More visits in third to fifth-grade classrooms

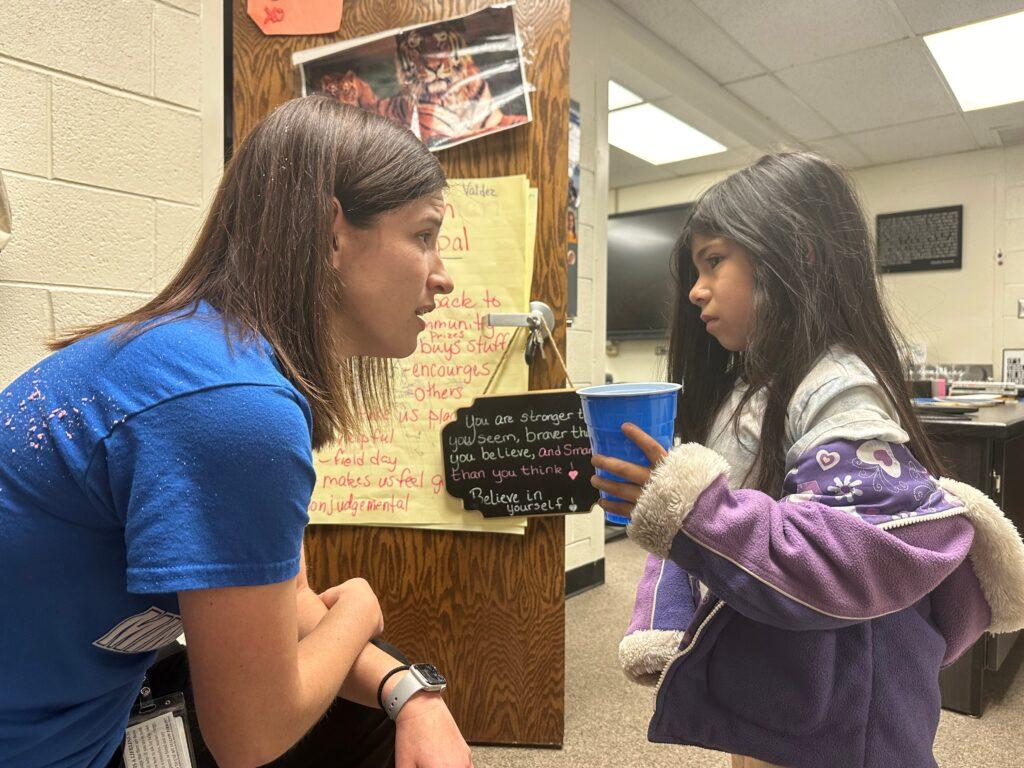

Harshman doesn’t just monitor and provide feedback. She’s helping students tackle problems and address worries. She hands out little white slips of paper for good behavior or takes a student aside who is struggling with bigger issues.

“Whenever I see the principal and the teacher working together it means two people can help us so we can get more work done faster,” said third grader D’Angelo.

“My principal Ms. Harshman says to always keep going,” said Max, a fourth-grader.

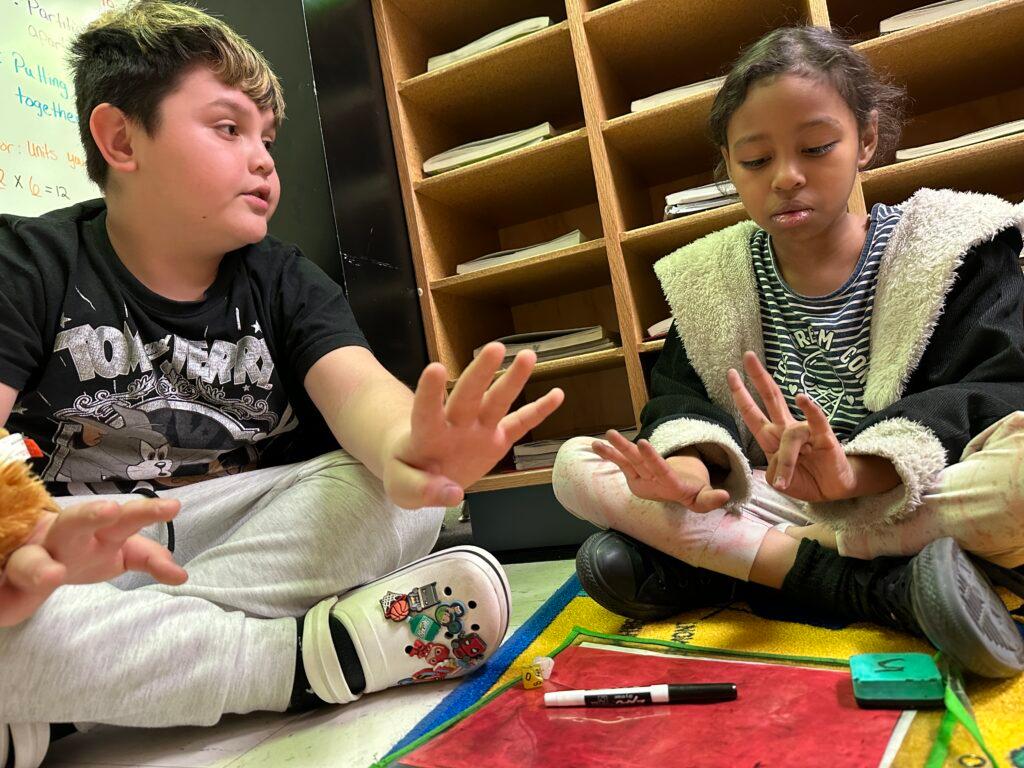

Fourth grader Max (left) helps his classmate Mallory learn to skip counting. Math teacher Leslie Ortega said giving children leadership opportunities to teach classmates builds their confidence.

Third grader D’Angelo buckles down on a tough problem figuring out the area of a shaded part of a shape on Jan. 25, 2024. He must be able to verbally explain what his strategy was and why.

11 a.m. - noon Lunch duty, supervising and being with children

Harshman grabs a slice of pizza.

The rest of the day, it’s candy and her favorite, Coke Zero.

Noon - 3 p.m. Classroom walkthroughs and relationship-building

A second key pillar in the school’s ascent is creating a sense of joy and safety in the school by building relationships with the students.

Every single student in Leslie Ortega’s fourth-grade math is focused and engaged. It’s rare to see this in a math class. All eyes are trained on Ortega. The kids say they adore her. Ortega, a nine-year veteran, craves feedback to continually improve her craft.

“Even being here nine years, sometimes I don't know,” she said. “And I even go to the new teachers and say, how are you doing this? What is the new trend for this? How can I fix that?”

Trainers drove home this point – know the culture of your students and build a strong relationship with each child.

“As long as you build that relationship and build that bond with the kids, they're going to love and trust you. This is their home. This is their safe place, and it's okay to make mistakes and it's okay to fail and we work together.”

She and Harshman circulate the room. To build confidence, Ortega paired kids with stronger math skills to teach others during a dice game. She gives kids who may struggle with behavior chances to show leadership.

Harshman thanks a kid for not giving up.

She whispers to another student “Good job,” but says she had a hard time hearing her next time speak a bit louder, with confidence.

“She usually comes in to encourage us … I like it when she comes in,” said Winter, 9, wearing a fur cap with a raccoon tail. “What I like about this school is they’re very understanding and they know and when someone might be having trouble with something … They are not just like ‘oh you’ll get it eventually’ … they actually try to see how the person is doing.”

And then take steps to identify what precisely are the errors in the child’s thinking to get them back on track.

The question remains: If Minnequa can make drastic improvements in test scores can it be replicated in other schools?

Harshman said Relay’s practices worked for her school. Maybe other schools need something else.

“It can be done, but you have to make the correct moves on what you need, right? What Minnequa did and the steps I took, isn’t necessarily what another school is going to need.”

Jenn Baugher with the Relay Graduate School of Education and Harshman’s coach, agrees. She said every school leader has a distinct vision for what they want their school to look and feel like so their levers for improvement may be slightly different.

But she said all schools that have seen dramatic improvement have an invested, talented leader who is willing to be coached.

“It's really intense work,” Baugher said. “I think sometimes it can be easier to maybe fall back on something that seemed to be working before … it's just really hard work.”

Harshman credits the school’s success to teachers staying and being open to feedback and coaching. Fourth-grade teacher Ortega credits Harshman with fueling Minnequa’s turnaround.

“She cares for the students, she cares for the teacher. She's willing to hear us out. She's willing to help us out, and the kids feel that love. If she gives us that love, we feel that love from her. And then we go and do our job and do the same thing with our children,” Ortega said. ”I can’t imagine working anywhere else.”

3 p.m. Harshman announces the winner of the hoverboard (Eladee) and does ‘shout outs’ to various classrooms about what she saw on her visits

She sprays silly-string at kids and teachers in the hall as Eladee picks up her prize. Then a first-grader approaches Harshman, inconsolable. She’s crying so hard she can’t get the words out. Harshman takes her back into her office and gives her a glass of water.

“See how it calms you down? It’s just a natural thing with water I’ve noticed.”

The girl tells her story about how when she dropped her pencil someone threw it across the room. Harshman tells the girl on Monday she’ll talk to the other students to teach them to make nice choices.

“Because it hurts your heart, right? It teaches us how we want to treat people. Now you know when somebody drops their pencil you should pick it up and give it to them. Sometimes the way you fight people’s mean ways is to just treat them with kindness, can you do that?”

Plus, Harshman said, now the girl knows the trick about drinking water to calm down.

3:15 p.m. - 4 p.m. Data meeting with third-grade math teacher Margaret Nelson

On the table are all the end-of-class tests her third graders took that day — to see how much they understood the lesson. The tests are divided into high, medium, and low based on comprehension.

The two conduct an intense analysis of each test for errors in thinking and the various teaching strategies and materials Nelson can use to correct those errors.

They conclude, that Nelson is doing a pretty exceptional job on the hardest part of a lesson.

“Your kids get the conceptual! They’re missing the computation. Easy win!” said Harshman. Nelson though, worries about where to find the time to get the kids to practice computation. It’s not happening in many homes so the limited window at school is all they have.

“I just want these kids to have a choice (in life) and there's so many barriers to that,” Nelson said.

4 p.m. - 6 p.m. Harshman wraps up and heads home

After helping out with two hours of basketball practice, Harshman finally winds down. The school partners with outside organizations like the YMCA, to bring extracurriculars to Minnequa students.

She tries to get everything she can done at the school to leave by 6 so she can have time with her own children.

“It's exhausting but absolutely worth it,” she said.

- Colorado educators strategize over how to best serve thousands of new immigrant students

- After 30 years, a new way to fund Colorado’s schools is ready for lawmakers’ eyes

- What happens when students are let loose at the stock show and a farm to learn by themselves?

- 15 years after a law gave more flexibility, innovation to schools, their test scores are a ‘mixed bag’

- It can be hard to get juvenile offenders back in school. A new proposal aims to make it easier — and students more successful