A new survey by the Colorado Health Institute sheds light on the often disastrous and far-reaching impact of long COVID in Colorado.

It found one in seven Coloradans who tested positive for COVID-19 had long COVID — they said they experienced COVID symptoms for three months or more.

Many surveyed said the illness had a big impact on work or school.

“Nearly half of those who had long covid had to take time off of work or school (about 138,000 people), and another third of them had to take reduced hours at work (more than 102,000 people),” said Lindsey Whittington, the institute’s data and analysis manager, and co-principal investigator.

The results come from the 2023 Colorado Health Access Survey, with questions asked in 2023 of 10,000 households, a robust sample of Coloradans.

Around one in 20 (nearly 20,000) had to leave their jobs, and a similar figure applied for disability benefits (around 24,000).

“This further highlights the financial struggles of those who tested positive for COVID and experienced symptoms that made it difficult for them to work,” Whittington said.

Nearly a quarter (62,000) suffered some other impact.

The survey said that Colorado’s labor market lost “tens of thousands” of workers due to long COVID.

The lingering effects of long COVID are estimated to have hit more than 300,000 Coloradans, though that figure is likely an undercount, according to the survey.

Nearly half of Coloradans 16 and older said they’ve gotten a positive coronavirus test at some point since the beginning of the pandemic in 2020. That equates to more than 2.2 million people, but the report notes the number is likely much higher because many either never took a COVID-19 test or got a false negative.

The survey gave participants an option to describe lingering, life-changing symptoms. Many said they had to cope with body fatigue and brain fog, which interfered with activities and hobbies. Many still reported problems breathing, a cough, or a need for oxygen or an inhaler.

“The results really didn't surprise me much,” said Clarence Troutman of Denver. He had a 37-year career as a broadband technician derailed by the virus. He caught it early in the pandemic, was hospitalized and on a ventilator for a time, and ended up staying two months. His symptoms, particularly fatigue, have improved some but also persisted.

“I can relate to some things on the list, mainly the career impact of it all,” he said. “It's truly been a life-changer.”

The data mirror what researchers at CU Anschutz have seen.

“I think they demonstrate what we have heard individually from patients in the clinic of the last four years and highlight the larger societal impact for long COVID,” said Dr. Sarah Jolley, a researcher with CU Anshutz and medical director of the UCHealth Post-COVID Clinic.

They are part of the large national observational RECOVER studies, which include 90,000 adults and children and more than 300 clinical research sites around the U.S., Jolley said.

The one in seven figure from the Colorado Health Institute’s survey seems low to Dan Stoot, a physical therapist at High Definition Physical Therapy in Englewood, who works with long COVID patients.

“The impact on lives, school, and jobs is very real,” said Stoot.

He added that often forgotten is the fact that these individuals no longer have active COVID and most lab tests come back as normal.

“But they have very significant functional deficits that prevent them from being able to participate in their lives as they did prior to having COVID,” Stoot said.

At times schools and employers “write them off as if nothing is wrong, we see the same pattern in brain injury patients,” he said.

Disparities in sex and disability, also shelter and food

The survey found women (16 percent) were more likely than men (11 percent) to report long COVID symptoms.

The 30 percent of people who already face a mental, physical, or emotional condition were more likely to suffer long COVID symptoms compared with the roughly 11 percent who don’t have those conditions.

The report also documented negative impacts on so-called long haulers in terms of housing and food.

People with long COVID symptoms were more than three times as likely to experience housing instability and more than twice as likely to face food insecurity.

The survey said that may be due to having to leave a job or cut down on work hours, causing them to be short of cash for basic needs. It noted that already existing social disparities might have “made it more likely that disadvantaged people would suffer from long COVID.”

New Clinical Trials Ahead

Help may be on the way, coming first from new clinical trials.

Jolley said the survey spotlights the importance of a multi-pronged approach in response, backed by Colorado's Lt. Governor’s Office and new resources coming from the federal government.

In fall 2023, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, via the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, announced nine grant awards of $1 million each for up to five years to fund existing multidisciplinary long COVID clinics nationally. The money will help serve those with long COVID, particularly disproportionately impacted underserved, vulnerable, and rural populations.

Jolley also said her team had started a pair of clinical trials with three more coming by summer.

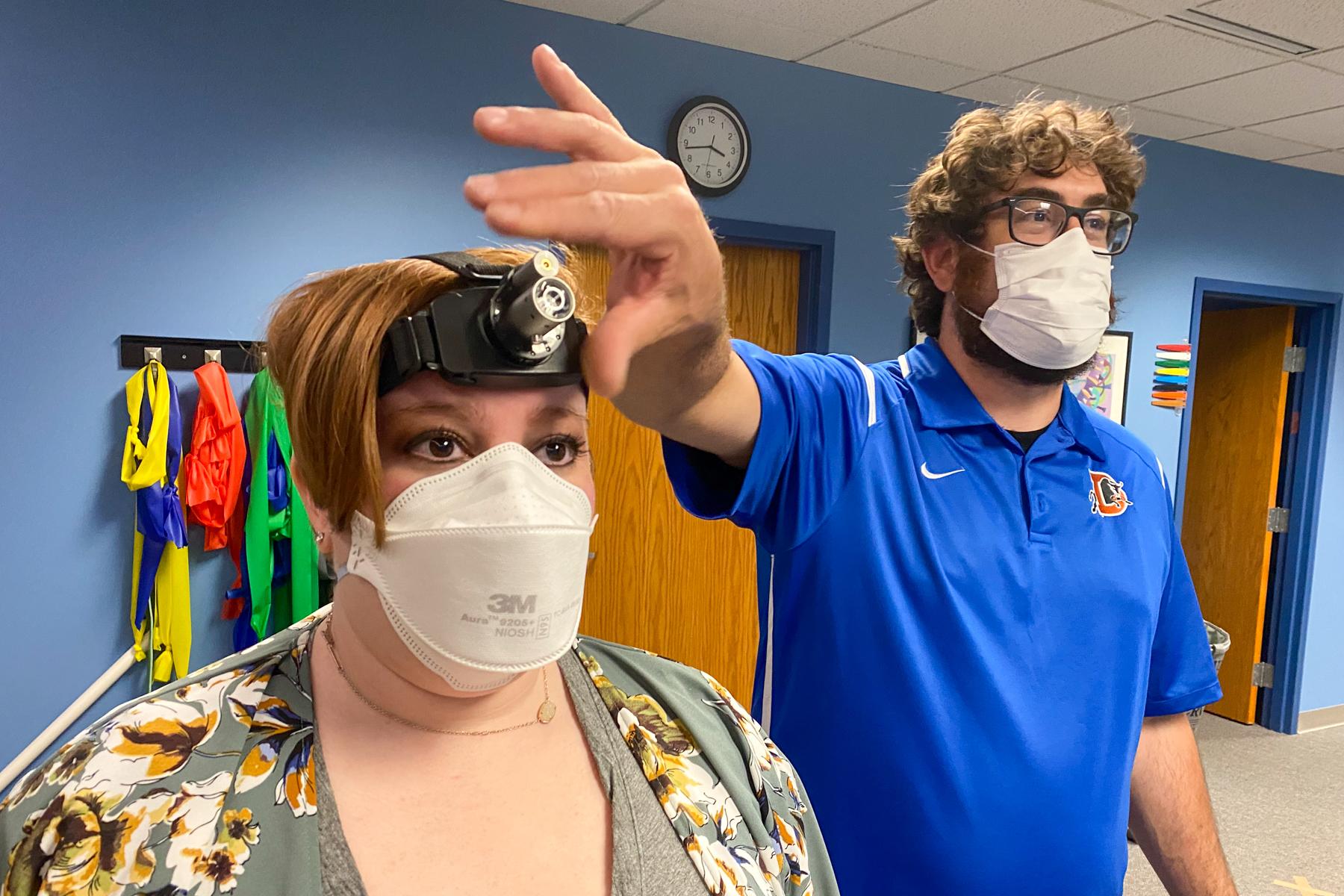

The active trials are looking at antiviral therapy Paxlovid for post-acute COVID symptoms and “non-pharmacologic therapies including cognitive retraining and transcutaneous (penetrating or absorbing through the skin) stimulation for long-term cognitive symptoms,” she said.

Future studies will examine drug therapies for “autonomic dysfunction” and COVID-related fatigue/sleep disturbance along with rehabilitation strategies for lessening intolerance of exercise.