John Avenson fell in love with his home more than four decades ago.

The year was 1981. That’s when Avenson, a young engineer at the Bell Telephone Company, caught an ad for an event called a Passive Solar Tour of Homes.

The free event invited anyone to see 12 homes designed to conserve energy by taking full advantage of the sun. In a special supplement to the Rocky Mountain News, the organizers promised to dispel any myth that passive solar homes were unattractive and unaffordable.

More than 100,000 people from around Metro Denver ended up joining the tour. Avenson drove from Boulder to Arvada to see every home, each a careful collaboration between federal scientists and a local building company.

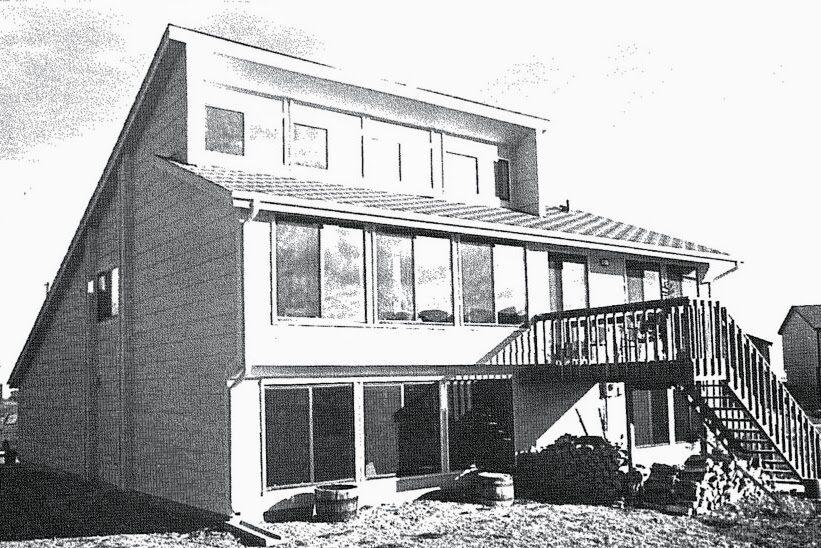

His favorite was a split-level home with a broad wall of south-facing windows. Unlike other models, it didn’t rely on finicky hot water panels to soak up solar energy. Instead, the sun warmed the interior, allowing the hot air to rise to the apex of the ceiling. A high-powered fan then moved the heat into a massive box in the basement full of river rocks, which stayed warm to hold back the cold overnight.

Avenson commissioned a version for himself in a new development in Westminster. Since then, he’s updated it with the latest in green building technology, adding high-performance windows, extra insulation, and automatic blinds controlled by indoor and outdoor temperature sensors. It all adds up to a minuscule amount of energy consumption. To stay warm in the winter, he says his heat pump requires a fraction of the power it takes to run a hair dryer.

“I am so passionate and angry that all homes are not built this good even today, because our country would be totally off of fossil fuels by now. Or just very small usage,” Avenson said.

The frustration led him to write Colorado Wonders with a question: why aren’t more homes built like his? And, more precisely, what killed the federal program behind the original home tour he attended in 1981?

A vision for a green home revolution

Avenson has already put some work into answering the question himself.

Entering his home is like walking into an expert science fair project. A monitor near the front door displays real-time data on the conditions inside the home and its current energy usage. Sensors track movement to flip lights on and off. Dozens of laminated labels draw attention to the LED lights and computer-controlled shades.

In the living room, an entire wall is dedicated to the history of the home. At the top is a copy of a front page clipping showing former President Jimmy Carter in Colorado to announce May 3, 1978, as Sun Day, a new holiday meant to celebrate the promise of solar energy research.

During his four years in the White House, Carter put solar energy at the center of his response to the 1970s Energy Crisis, when an embargo in the Middle East exposed the U.S. economy’s desperate dependence on foreign oil.

Carter’s passion not only led his administration to put thermal solar hot water panels atop the White House. He also called for a moonshot, setting a goal for the country to rely on the sun for 20 percent of its energy by the end of the century.

“This is a bold proposal and it’s an ambitious goal, but it’s attainable if we have the will to achieve it,” Carter said in 1979.

At the center of the project was the Solar Energy Research Institute in Golden, Colo. The federal facility has since evolved into the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, which works to commercialize everything from hydrogen fuel cells to sea wave energy generation. In its early years, however, the institute focused on early solar panels and passive solar homes.

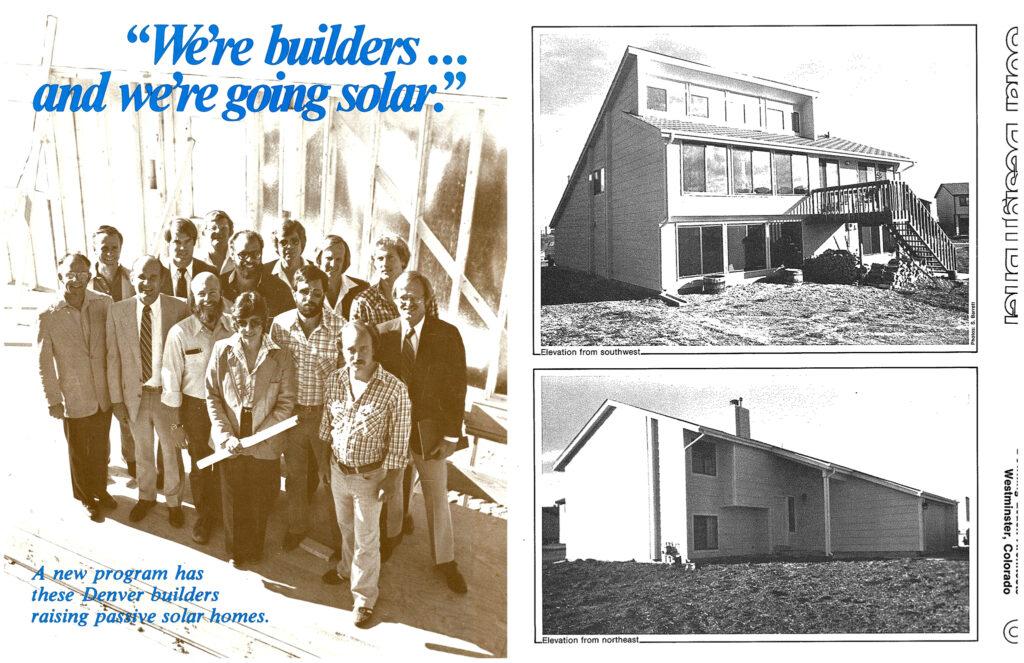

The facility organized the tour behind Avenson’s home. In 1980, SERI launched the Denver Metro Home Builders Program to bring passive solar concepts into common commercial practice.

The program recruited local construction companies to participate, offering to revise their current blueprints to maximize potential energy savings through the careful placement of windows and heavy materials to absorb thermal energy. In exchange for building the designs, SERI agreed to organize the parade of homes to attract potential buyers.

Denis Hayes, the institute’s executive director and an organizer of the first Earth Day, confirmed the two-week event was a massive hit. Besides drawing thousands of visitors, it yielded 31 sales contracts and more than 60 preorders for additional passive solar homes.

“One of the home builders actually had to rip out all of his carpets after two weekends because so many thousands of people had gone through that they destroyed the carpets,” Hayes said.

After speaking to his superiors at the U.S. Department of Energy, Hayes was optimistic the institute could replicate the pilot program in a dozen cities. It was a chance, he said, to promote passive solar design nationwide by proving it was relatively cheap and easy to implement through traditional building methods.

“I'd like to think it would've worked, but we never got a chance,” Hayes said.

A “blood bath” for solar energy research

By the time of the home tour, the future of the laboratory was already perilous.

Ronald Reagan won the White House in the 1980 presidential election, raising questions about whether the federal government would pull back its investments in renewable energy research.

Hayes was optimistic at first. Solar energy was broadly popular, and he figured it fit with a conservative vision of self-reliance where citizens took responsibility for themselves rather than relying on distant forces for support or resources.

Then he heard rumors the institute had run out of luck. The Reagan Administration worked with Congress to cut its budget from $130 million to just $30 million, forcing it to lay off hundreds of direct employees and contractors. Hayes was asked to resign, but, in a parting shot, he gave a speech blaming the cuts on “gray bureaucrats in Washington” who refused to see the promise of solar energy.

“It was a bloodbath,” Hayes said. “I can't help but think that this was calculated by someone up there to try to make it so bloody that it would be really difficult to ever restore it to the kind of prominence it had previously enjoyed.”

The move doomed any hope for SERI’s home-building program. Today, Hayes suspects the Reagan Administration was motivated by its deep ties to the nuclear and fossil fuel industries, but he admits he’ll never know for sure.

What’s left for Hayes is frustration as other countries capitalize on the institute’s early research. China is now a photovoltaic powerhouse, owning 80 percent of the world’s solar manufacturing capacity. Meanwhile, Europe is the international leader in energy-efficient buildings, easily besting the U.S. in a recent ranking from the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy.

But Hayes is glad the tide has started to shift back toward Carter’s vision. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory is now a major beneficiary of new federal investments, including $150 million from President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act. The U.S. solar industry is booming, and he acknowledges the country’s homes have made gains in energy efficiency.

“We have made the kind of progress that we'd hope to make,” Hayes said. “It's just that we're making it 25 years later than we had planned to.”