By any measure, Michael G. Jackson's life was spiraling.

In September 2023, after his second violent felony arrest in six months, he was released from a Denver jail with a promise not to commit new crimes, give up his guns, and stay away from alcohol.

A few weeks later, Denver Police said he shot and killed Uber driver Goitom Hagos, 51, in a drunken shooting rampage.

Neither Hagos nor his passenger had contact with Jackson before the shooting. No road rage was reported. No motive has been publicly disclosed. The incident appears totally random.

“I really do wish that they both didn't come across each other,” said Hagos’ nephew, Yohannese Gebremedhin. He said his uncle supported many people financially, and often sent money back to family in Tigray, a northern region of Ethiopia from which he immigrated in 1992. A GoFundMe was set up to help the family. “Their lives and the people around them are changed forever.”

Just a few weeks before the shooting, Denver prosecutors tried to convince a judge to keep Jackson in jail on a $25,000 cash-only bond after his second felony arrest in half a year, for strangling his partner. In a hearing that lasted about 10 minutes, the judge instead allowed Jackson to be freed on a personal recognizance bond, requiring no money for his release.

“Very surprising and disappointing,” Denver District Attorney Beth McCann, said in an interview. “Just not the kind of person that should be out, given the nature of the crime that he was charged with.”

Jackson’s case offers a window into what reformers say are the perverse features of a money bond system — where an impoverished low-risk defendant can languish in jail awaiting trial, while another defendant with means can pay for release. And some, like Jackson, are released with little more than a promise to return for future court dates.

“Some of this conversation about cash bond should really be a conversation about do we want to detain this person?” said Rebecca Wallace with the Colorado Freedom Fund, a group that pays relatively small bonds for cash-strapped defendants. “You want a judge openly looking at ‘Do we think that there's a serious public safety risk if this person is released.’”

When someone is arrested for a serious crime, they are presumed innocent and must appear before a judge who will set conditions for their release while awaiting trial. Bonds can be millions of dollars for murder defendants or just hundreds of dollars for a car theft. The hearings happen at a rapid pace, with judges and prosecutors sifting through arrest reports and risk scores, trying to protect the community and set a price that ensures the defendant will return for court dates.

Money is no guarantee of community safety. Earlier in February, a Denver defendant allegedly decapitated and dismembered a man after posting a $10,000 bond while awaiting trial on attempted murder.

Meanwhile, 90 percent of defendants released on a no-money PR bond (but with some supervision, like GPS monitoring) are not arrested for a new crime, according to data from Denver pretrial services.

“I think that there's increasingly wide agreement that money is a poor proxy for safety,” said Wallace.

'Broken on both ends'

In 2019, a modest attempt at bond reform failed in the Colorado legislature, and the state task force that recommended it, the Colorado Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice, disbanded the same month Hagos was killed. Gov. Jared Polis created a new task force, which is currently meeting to discuss how a future criminal justice task force will be structured. At the same time, legislators may ask voters to decide in the fall whether to restore the concept of no-bond holds for those charged with capital crimes.

Ten years ago, New Jersey had a system similar to Colorado’s, where low-risk defendants could sit in jail awaiting trial because they could not afford bond but potentially violent offenders could pay to get out. There, many advocates, public defenders, prosecutors, and judges agreed the approach to pretrial release was “broken on both ends,” said Martin Cronin, a retired New Jersey Superior Court judge.

In the old system, for cases with profound community safety concerns, Cronin said prosecutors and judges would come up with a bond amount they thought the defendant wouldn’t be able to post.

“If it's a really dangerous person, and there was a concern that the person will go out and hurt people when they get out, it's like, ‘Please, I hope you don't make the bail.’ Now what kind of system is that?”

Martin Cronin, retired New Jersey Superior Court Judge

So New Jersey voters enacted pioneering reforms, and cut money out of the equation altogether. Now, most defendants are released awaiting trial. Prosecutors request to hold inmates they believe pose a risk to the community — in those cases a motion is filed for detention and a hearing is held in front of a judge within three business days.

“It's a harder system to implement,” said Cronin. “Because it requires more preparation, it's more fact-intensive. But the results? It's more fair to the defendants and the victims.”

A report produced by a joint committee in New Jersey said prior to reform, 12 percent of the jail population remained in custody because they couldn’t post bail of $2,500 or less. By 2022, that number had decreased to almost zero. Also before reform, more than half the jail population were for non-violent offenses, now two-thirds of the jail population are people accused of the most serious violent crimes.

Has it made New Jersey safer? Trying to draw cause and effect from crime statistics is difficult, but it’s clear that the changes in New Jersey didn’t lead to a substantial increase in crime, said Cronin.

New Jersey’s violent crime rate has fallen almost every year since cutting money out of bond hearings, in 2022 there were 203 violent crimes per 100,000 people according to the FBI data. Colorado’s violent crime rate was more than double that of New Jersey and has risen 60 percent in the last decade. (There are signs that violent crime declined in 2023 in Colorado, preliminary data shows murders and aggravated assaults both down compared to 2022.)

New Jersey’s approach allows judges to spend more time on the toughest cases, and do a deeper examination of the risk to the public if a pretrial defendant is released.

And time is in short supply. In Denver alone, there were about 10,000 bond hearings in 2022 for serious crimes: felonies, domestic violence, and violent misdemeanors. Judges have other duties besides setting bond, so if two hours a day are set aside for those hearings — 365 days a year — each hearing gets less than 5 minutes. Not much time for what can be a life-or-death decision.

Jackson’s case shows how Colorado’s multi-faceted approach to pretrial release — cash or surety bond or personal recognizance — can lead to rushed hearings and unwanted outcomes.

“As long as we have a cash bond system,” said Boulder County District Attorney Michael Dougherty. “You can have two people who commit the exact same crime with the exact same criminal history and have the exact same bond set, and one is going to be in jail for six months and the other is going to be out in six hours.”

“We need to do more to improve and reform the bond system without sacrificing public safety in the state of Colorado,” said Dougherty.

- First-degree murder suspects can now post bond in Colorado — some politicians want to change that

- Nearly half of Colorado counties have 10 or fewer attorneys. A new grant aims to expand legal access for Coloradans

- Holding law enforcement accountable goes beyond charging police officers. It’s about stopping harm from happening in the first place

“Good luck to you”

On Aug. 31, Denver Police responded to a report of domestic violence in an apartment complex next to Fairmount Cemetery.

Jackson’s partner told him that she wanted to end their relationship.

“Jackson, who was drinking, then got on top of her on the bed in the living room. He placed two hands around her throat for an unknown period of time until she could not breathe,” reads the police probable cause statement.

Jackson was placed under arrest for felony assault and taken to jail. The next day, Friday, Sept. 1, 2023, before the Labor Day weekend, Jackson appeared in a Denver courtroom for his second bond hearing in six months.

Earlier that year he had been arrested for felony assault, for punching two Denver police officers. Jackson’s mom told police he was blackout drunk. He was released on a PR bond, and directed for veteran’s court. (McCann, the Denver DA, agreed that a PR bond made sense here, it was his first violent offense.)

But despite his growing violent criminal history, this new bond hearing in August 2023 lasted only about 10 minutes, an estimate based on the length of the transcript. Denver County Court, which presides over bond hearings refused to release the recording, citing a 2023 policy change.

Jackson’s attorney, a public defender, argued for yet another personal recognizance bond. He’s a military veteran and he’s never failed to appear in court, she said. An assessment by Denver’s pretrial services called a CPAT-R score put him in the lowest risk category.

The magistrate called on the deputy district attorney to make his case.

“The People have high community safety concerns here, just given the facts in the probable cause statement,” said Manuel Sanchez-Moyano, who noted Jackson scored high for domestic violence risk. He asked for a $25,000 cash-only bond — Jackson would be required to pay the full amount to be released.

The magistrate hearing the case, Kathleen Boland, didn’t engage with any of the DA’s arguments. She immediately set the conditions for Jackson’s release without paying anything: he was required to stay away from the victim and he had to promise to relinquish any firearms.

Authorities said he did not keep that promise.

“I think that our judges do try to weigh things carefully by and large,” McCann, the Denver DA, said. “Where we see more of the issues that we see is with the magistrates on the weekends and so forth that aren't doing it regularly, that are part-time.”

Boland has been part-time in Denver as a magistrate for almost 30 years, according to an online biography. But her private practice expertise appears to be focused on non-criminal law: “emphasizing estate planning, probate, and mediation.”

Boland declined to speak with CPR News.

At the end of the hearing, Boland told Jackson to stay away from alcohol and drugs. All three of Jackson’s previous arrests at that point were alcohol-related: the DUI, the police assault, and now the strangulation. “If that's an issue for you, you need to get help with it,” she said, according to the transcript.

“Come back, don't commit any crimes out of custody, comply with the protection order,” Boland said to Jackson near the end of the hearing.

Finally, she added: “Good luck to you.”

Seventeen days later, at 9:29 p.m. six gunshots were detected by Denver Police sensors. Police found an Uber crashed against a tree. The female passenger in the back had a minor injury and she was spattered with blood. It wasn’t hers.

The driver, Hagos, had been shot four times in the left side. Hagos was pronounced dead upon arrival at a nearby hospital.

Jackson was found less than a mile away from the scene with two handguns. He had also shot and injured a security guard and stolen a car before fleeing, police said. He later told investigators he was so drunk he couldn’t remember any details of the shooting.

'If I had a magic wand, I would want a better risk tool'

In addition to New Jersey, Illinois and Washington D.C. have undertaken substantial bond reform — taking money out of the system, to avoid criminalizing poverty, while focusing instead on community safety when releasing defendants from jail awaiting trial.

Many in Colorado dream of having such a system here, but Tristan Gorman, Policy Director for the Colorado Criminal Defense Bar said the details of such a system matter.

It would be ideal to spend more time reviewing potentially dangerous cases, but “you cannot have robust hearings at the volume that we're at so you would have to do things to chip away at the number of people who end up in jail awaiting a bond hearing.”

Gorman argues that any reforms must result in more people being released pretrial. Defendants are presumed innocent, and even short stints in jail can lead to lost jobs, housing, and relationships. And the longer someone waits in jail the more likely they are to plead guilty for a plea bargain just to get out of jail, which Gorman said is unjust.

Denver District Attorney Beth McCann said eliminating cash bonds is an interesting concept, but the trick is assessing community safety.

“That is the key: how do you predict, do you have a good assessment tool that can really predict future behavior?”

An effort to reform Colorado’s system in 2019 failed at the state legislature, it wouldn’t have eliminated money bonds but would have, among other things, standardized risk assessments across counties.

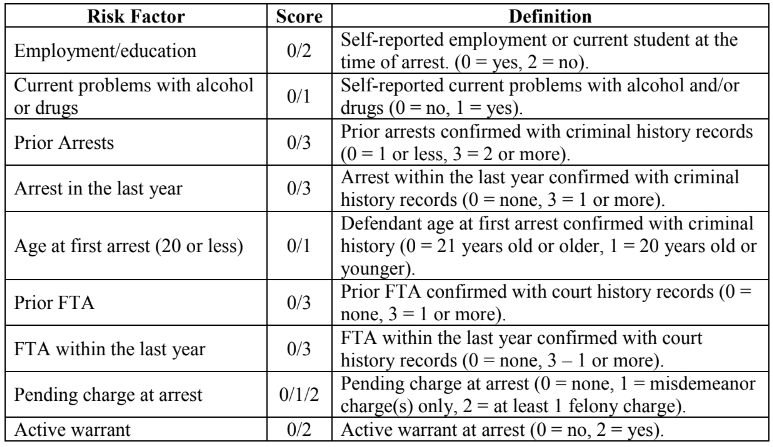

Many counties in Colorado use that same CPAT-R tool used in Denver. It was created more than a decade ago by analyzing a sample of 2,000 defendants in the state’s largest counties, looking for common factors that predict failure to appear or committing new crimes.

The tool has been statistically validated by the University of Northern Colorado, but several District Attorneys around Denver were uncertain about its usefulness in predicting safety. It focuses heavily on failure to appear (FTA) for court dates. And it relies on self-reported answers to some key questions.

Jackson had a low CPAT-R score, in part, because he self-reported that he was employed (he said he was about to start a job at a security company) and didn’t have a problem with alcohol, despite a DUI and then two arrests for violent alcohol-related offenses.

Some jurisdictions in the U.S. — though apparently none in Colorado — use a risk assessment tool developed by a foundation, Arnold Ventures, using data from 750,000 cases across 300 jurisdictions. The questions look similar to Colorado’s CPAT-R but put a particular emphasis on measuring the likelihood that a defendant will commit a violent crime while awaiting trial.

Though Arnold Ventures admits that no assessment tool can totally predict human behavior, there will always be some risk to the community in releasing arrestees.

“If I had a magic wand, I would want a better risk tool,” said Alexis King, the 1st Judicial District Attorney for Jefferson County and Gilpin County. “Ultimately, if we want more consistent decisions from everyone standing in a courtroom, having the perfect risk tool is a great way to get started.”

King has implemented a form of what New Jersey has done, a kind of “hold and release style” model. If a defendant is a risk to public safety, her deputy DAs ask for a high cash bond amount, which most can’t pay. If they’re a low risk, then her prosecutors ask for a PR bond.

“So what really bothered me as a DA, was you could get a different bond argument depending on who your judge was, who your DA was, and who your public defender was. And that to me is so inconsistent, and not what I think anyone in the community would want,” King said.

Without a better risk tool, King said she aims to put experienced prosecutors in the bond hearings. While judges have the ultimate authority to set bond conditions, King said their data shows judges accept the prosecutor’s requested bond amount 90 percent of the time.

So, while the state has punted on large-scale bond reform, Colorado’s district attorneys will continue to hold tremendous power to shape how the bond system works in the state.

“One of my colleagues said to me once, ‘I think bond is one of the most important arguments that a DA can make,’” King said. “And I don't think that that's how we treat it necessarily in the realm of things that we have to do as prosecutors.”

The stakes are high: most felons will be released from jail while awaiting trial, but release the wrong person, and the community is put at risk.

Hagos’s family is now left with painful questions.

“And you can say what you want with regards to, ‘There's always going to be bad things that happen in the world,’” said his nephew, Gebremedhin. “But that doesn't mean we can't take it upon ourselves to do what we can to at least maintain some order and civility with these kind of things. And it doesn't seem like he was supposed to be out there in the first place.”

Correction (March 5, 2024) - An earlier version of this story mischaracterized the percentage of people who commit any new crime while on pre-trial release with a PR bond.