Hayfields and rugged peaks create a picturesque setting for humming machinery churning up water in three small ponds. These aerators are working to add oxygen to mud-colored wastewater slowly moving through the lagoons.

The ponds, or lagoons, are a primary element in the wastewater treatment plant at the edge of Westcliffe, a small town in the Wet Mountain Valley, about an hour west of Pueblo.

The Round Mountain Water and Sanitation District serves about 1,300 people in both Westcliffe and nearby Silver Cliff. Plumbing in about 700 homes and businesses there connects to the district’s wastewater treatment facility.

The combined population of the two towns in the district's service area has seen some ups and downs since 1970, but is now triple what it was then.

"It was never meant to treat as much waste as it is," District manager Dave Schneider said. "So the treatment's been compromised."

It's a story familiar to a lot of rural communities across the state. And as more people move into small communities, some, like Westcliffe and Silver Cliff, struggle to keep pace with infrastructure requirements, including the good old-fashioned toilet flush. Combine the growth with what are now more stringent environmental regulations and it can add up to costly problems.

Wastewater needs to be cleaned up before it gets to rivers and creeks

When the federal Clean Water Act was put in place more than 50 years ago to help protect the nation’s water resources from contamination, each state was charged with implementing and enforcing the act’s standards. Those requirements have gotten more stringent over time.

Schneider said his district's aging lagoon system has been out of compliance for years. So they had a new, modern, mechanical system designed to meet the current standards.

"This mechanical treatment plant turned into a 120-foot-long monster," Schneider said. "Three stories tall."

And, it was wildly cost-prohibitive for the tiny community.

Nathan Moore manages the Clean Water Program at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, the agency tasked with overseeing compliance.

“We recognize that small communities face challenges in implementing wastewater treatment,” he said. “Wastewater treatment is an essential service to a community and not one that can be turned off. So we need to find the long-term solution.”

Moore said in general, the agency does provide technical and financial assistance to help small communities meet requirements.

Tiny organisms and technology

But Schnieder's own research found what could be a cost-effective solution that utilizes an updated lagoon system. In it, customized microbes help remove the contaminants specific to a particular place.

To test them, Schneider dumped a small box of the microbes into one of the failed lagoons.

“I have to say I was skeptical at first,” he said. “But within three days. They did something. It's like I didn't want to put my hand in the water, (like) they were like piranhas or something.”

There weren’t really any sharp-toothed fish involved. The tiny specialized organisms were eating and digesting the contaminants.

Scott Powell of Centennial-based Powell Water is helping the district with the proposed system. Powell calls it bug ranching.

“Our bodies don't digest all of our food. So the food comes into here and we basically have a feedlot for bugs,” he said. But the system also requires some added oxygen.

To do that, the district is working on a plan for underwater bubble diffusers that are more efficient than the current aerators, as well as some other modifications to the existing lagoons.

It’s possible they'll also need a second step called electrocoagulation, a technology first discovered in the 1880s that uses electricity to help remove contaminants.

“So normally in a healthy lagoon treatment system, it comes to the clarifying pond. It should look like clear lake water,” Schneider said, scooping a bucket of dirty water from one of the lagoons. “Well, as you can see, this is far from clear lake water.”

To demonstrate the process, Powell pumped the murky water into a small model system that sends electricity through metal plates as the water flows around them.

“When the electricity goes through the water, the reaction happens on the surface of those blades,” he said.

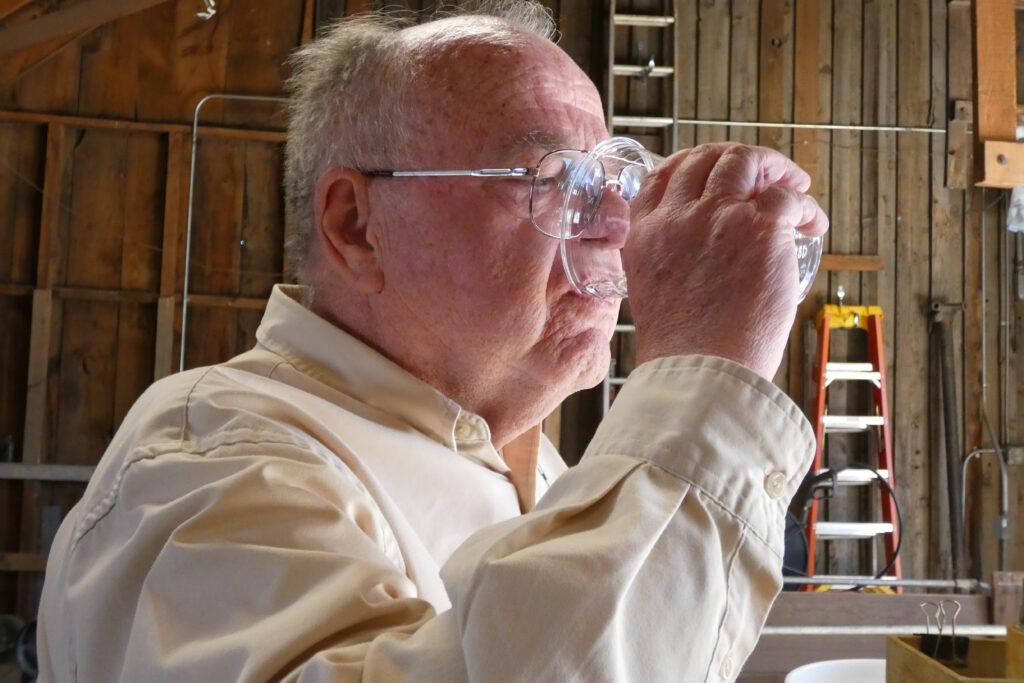

The water then passed through a filter and dripped into a cup. It was clear. Powell took a sip and described it as flat-tasting.

Schneider said it's difficult for a lot of people to imagine taking that drink.

“The e coli, all the bacteria, everything has been cooked and fried out of it,” he said. But “your brain's like 'I just saw that come out of that nasty bucket and no, I'm not there yet.'”

Proving it works

Schneider needs to prove to the state that this treatment method will meet the current regulations. He’s been working with CDPHE for several years now to put that evidence together.

“We are hopeful that it will be a good solution for them,” the state's Nathan Moore said, “but we just have to see what the site specific data shows.”

Schneider hopes to get approval for a pilot project later this year that will update the existing lagoons for the new process. The district will also run tests using a small electrocoagulation unit to see if that step is necessary. If successful, this project could help provide solutions to the many other rural wastewater systems throughout the state that are faced with similar compliance and expense problems.

- A Noxious Weed Is Bringing A New Level Of Fire Danger To The West

- Two Colorado towns look to preserve view of starry nights

- Meet Colorado’s first ‘International Dark Sky’ community

- Mapping search and rescue data shows dangerous patterns in Southern Colorado mountains

- Proposals to replace the name of southern Colorado’s Kit Carson Mountain are coming in, but federal board says debate to change it still needs to happen