Ak'Ylez Escamilla, a senior at Denver’s North High School, is considering his options.

He wants to be a police officer. Technically, to work for Denver’s police department, he doesn’t need a degree. But his salary would be higher if he had one. He’s got his eye on two colleges: Greenville University and North Park University in Chicago.

They’ve offered football scholarships and the pull to leave home is big.

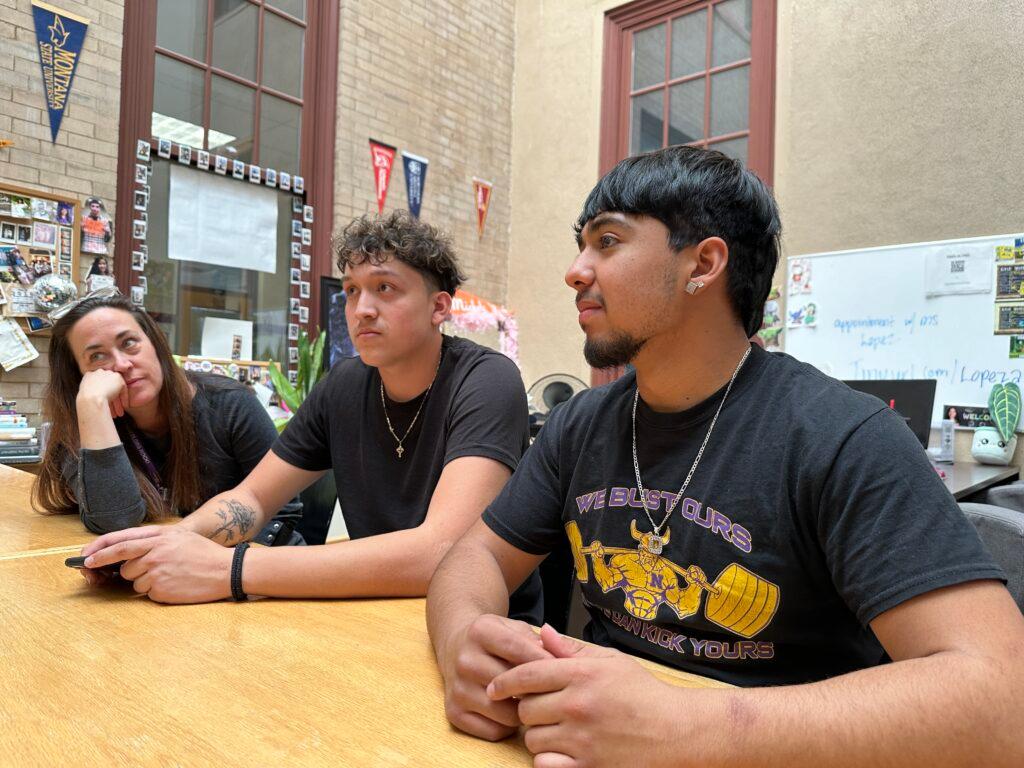

“I want to get out of state,” he said, sitting in a North High career counseling room. “Different scenery. Start fresh.”

His college advisor Michele Lopez asks Escamilla if he got football offers in Colorado — would he stay?

“Probably, yeah.”

If he leaves Colorado, Escamilla will join a growing number of high graduates enrolling in college out-of-state because of better scholarships. Almost 30 percent of high school students left in 2021– up 4 percent from the previous year. Data show when a Coloradan stays in Colorado for college, they’re much more likely to stay here – and the state is desperate for workers.

A new legislative proposal offering income tax credits to encourage students to attend a four-year college is the latest in a growing list of state measures trying to get Colorado students to stay here and eventually take in-demand, good-paying jobs.

Four members of the influential joint budget committee are sponsoring the bipartisan proposal that’s estimated to cost $100 million -- but the incentives are only triggered in years where there is a significant TABOR surplus.

“It's all about increasing affordability for college,” said sponsor Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer. “And then also really working to keep Colorado students in the state while we're meeting these workforce demands.”

Committee chair Rep. Shannon Bird said Colorado doesn’t do a good job of educating its own high school graduates. Less than a third actually complete any type of post-secondary credential in Colorado six years after graduating; others get better scholarship offers out of state.

“Colorado is a net importer of talent and this tax credit will hopefully invest in our own people so we don’t have to recruit people from out of state,” she said. It’s not a viable strategy anymore with in-state migration slowing, declining birth rates, and an aging workforce.

One hand tied behind its back

The state has to import workers largely because, compared to other states, Colorado is fighting to keep students here with one hand behind its back.

“Due to our state Constitution, it's difficult for the state to make meaningful investments directly into our universities,” said Bird.

TABOR, or the Taxpayer Bill of Rights, restricts how much revenue the state government has to spend on higher education. That has left Colorado with one of the most poorly funded higher education systems in the country, leaving colleges with less capacity to provide financial aid than many institutions.

Todd Saliman, president of the University of Colorado, said that has brought out-of-state recruiters here.

“There are many, many institutions who have recruiters in Colorado who are recruiting our high school graduates to go to school in other states, and they offer significant financial aid.”

That’s likely to ramp up even more with a demographic drop in the number of college students hitting in 2025.

The new legislative proposal would offer students two separate income tax credits to encourage enrollment in four-year universities.

If a student graduates from a post-secondary institution in a field relating to what the state’s talent pipeline report defines as a “top job,” students would earn a tax credit. The amount of the incentive depends upon the type of credential or degree a student gets. The incentive would be $250 for the completion of a certificate less than one year, $500 for the completion of a certificate taking between one year and two years, $1,500 for graduates of an associate’s degree program, and $3,000 for graduates of a bachelor’s degree program, according to the bill.

Those so-called top jobs are in high demand: computers, business and finance, engineering, farming, installation and repair, legal, transportation and moving and health care, among others. The list is 178 occupations long and all provide a living wage. In many of the fields, there are two open jobs for every applicant in Colorado.

“We just know that the numbers aren't playing out right and we really need to start incentivizing people to go through their post-secondary education to get these good paying jobs,” said Kirkmeyer.

A second incentive is aimed at students who transfer either community college or college credits earned in high school to a Colorado four-year school. Students would earn $50 per credit hour for every college credit transferred after they earn 15 credits at the university. If a student transferred 60 credit hours, they’d get about $3,000.

“The best way to make a four-year degree cheaper is to transfer credits to a four-year institution,” said Saliman.

In the best-case scenario, if a student knows what they want to do in life as a junior in high school, graduates with an associate’s degree while in high school and transfers to a 4-year in a “top job” field, they could pocket $6,000 by the time they graduate.

Would the tax credit be enough to keep students here?

North High School counselor Kathy Hoffman and Michele Lopez, a Denver Scholarship Foundation college advisor, do some quick calculations on their phones. The average North student earns about 6 to 12 concurrent enrollment (college) credit hours, amounting to a $300-$600 tax credit under the bill.

“I don’t think $300 after getting 15 credits in college would incentive them to go,” said Lopez.

Hoffman agrees.

“These kids are working part-time jobs and they're getting a $600 paycheck in two weeks or something.”

Lopez explains that they coach many first-generation students on the long-term benefits of post-secondary education like higher wages and more job stability. But they say it can be hard to convince students to attend. Hoffman said the other challenge is this:

“We have so many kids when you ask them, ‘what do you want to do as a career?’ And they have no idea.”

Sometimes information on Colorado’s various incentive programs doesn’t trickle down to students. Ak'Ylez Escamilla, 17, who wants to be a police officer, wasn’t aware that another Colorado program would pay all his tuition and fees to study law enforcement at a community college. He knew that Denver's police department has a cadet program for those interested in police, fire, or sheriffs departments. Students can work part time within their field while receiving paid in-state tuition and books so long as the candidate attends Metropolitan State University of Denver or the University of Colorado. But Escamilla is interested, as well, in playing football.

The two counselors would like to see Colorado publicize and streamline incentives and structure high school so kids get more career experiences. Lopez said she’d like to see career information embedded throughout the curriculum, in all classes, making crystal clear what the connections are between what students are learning and the real world.

“The schedules are so tight,” she said.

The incentive might not convince seniors to go to college, but it could help those already intent on going, the counselors said.

Hoffman also hopes it would help with the North’s college matriculation rate.

She proudly shows off photos on her wall of former students who’ve graduated from college. When Hoffman arrived at North in 2010, 6 percent of students went on to get a credential within six years. Now it’s 13 percent. Once enrolled, she said 62 percent go onto a second year.

“I'm hoping that just even that little bit of money will incentivize them to maybe just finish a degree instead of just starting and stopping.”

The proposed incentives are dependent on available state revenues and are tied to the amount of TABOR surplus in any given year. For example, the incentive would be fully available in any year in which there is a TABOR surplus of $750 million or greater.

The incentive drops by 50 percent if the forecast is between $750 million and $500 million, and disappears if surplus revenue is below $500 million.

“We never want the state to be in a bad spot in the event of an economic downturn or state revenues decline,” said CU’s Saliman, a former state budget director.

The bill doesn’t yet have a committee hearing scheduled.