It’s no secret that trees make our lives better and healthier.

Trees help clean the air, filter the water, and provide shade. In fact, studies have also shown that being among trees — whether that means walking in a city park, going on a hike or even looking through your bedroom window — has a plethora of mental and physical health benefits.

Time in nature has been shown to have a direct correlation to a reduction in stress and anxiety and improves our ability to focus and boost our mood.

Trees also play a critical role in fighting against climate change — they remove carbon dioxide, a potent greenhouse gas, from the air. This, in turn, helps slow the buildup of carbon that has been warming the planet.

So in some ways, it’s easy to think about the big impacts of trees; their presence is crucial for all life on earth. But have you ever thought about that one tree, your favorite tree, that has had a big impact on your life? Maybe it was the tree in the park where you would sit and read, or the sapling you planted in your parents’ garden, or the one that you used to climb its branches with your siblings.

This question is what inspired Denver Botanic Gardens’ new film “A Branch of Us.”

“For me, that tree is in my grandparents' front yard in Laramie, Wyoming,” said filmmaker and producer Billy Kanaly. “It's a blue spruce, it's massive and beautiful. My grandparents have unfortunately been gone for quite a few years now. But that tree is still there.”

Kanaly hopes the Denver Botanic Garden film gives visitors a sense of wonder and deeper appreciation about the trees around them. He says most trees we see will and have far outlived us. By asking the simple question, “What is their story?”, we can better understand how they got here and maybe learn something from trees in the process.

“The trees can't talk, so it's the people who speak for the trees and on behalf of the trees that really give those trees a voice and that’s really what the film is about,” Kanaly said.

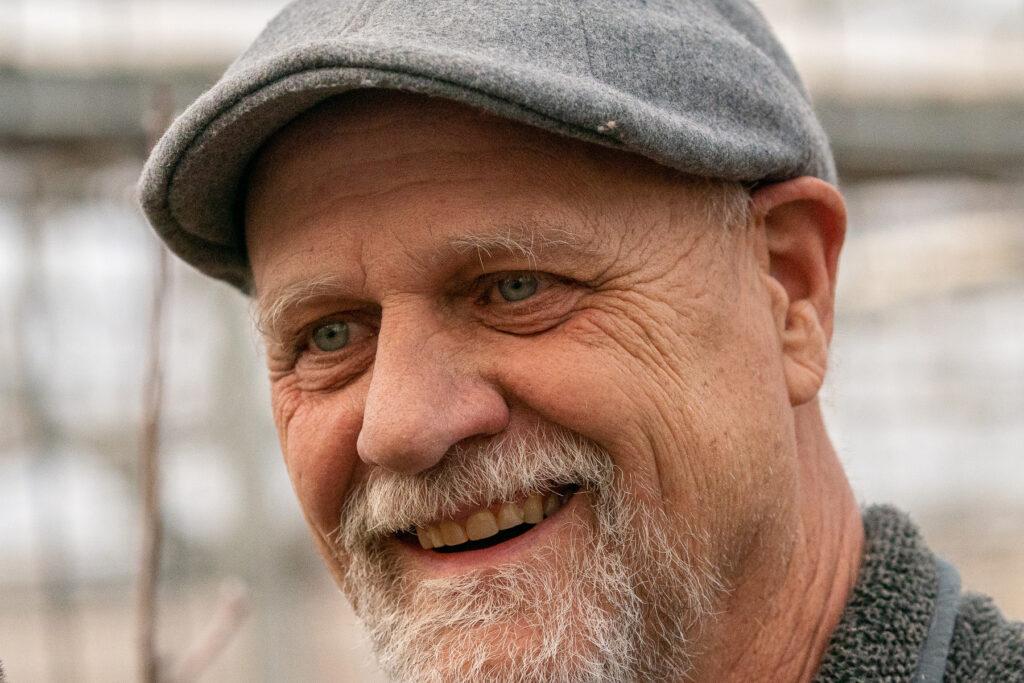

The film, which premiered in January, features the stories of four unique and special trees and the people who care for them. One of those people is Scott Skogerboe, a horticulturist based in Fort Collins. Skogerboe has spent the last few decades dedicated to tracking down and bringing back to life historic trees — trees that would have otherwise remained in the pages of history textbooks.

Colorado Matters senior host Ryan Warner interviewed Skogerboe surrounded by young trees and shrubs, in one of the horticulturalist’s greenhouses at Fort Collins Wholesale nursery.

You can view the film, “A Branch of Us,” that Scott and his trees are featured in at the Denver Botanic Gardens. The film is free to guests and will be playing four times a day, every day, for the next year.

Read the interview

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Ryan Warner: This apple tree, you actually have a few of them potted, has some incredible lineage. Tell us about that.

Scott Skogerboe: These come from the last remaining tree planted by Johnny Appleseed. What these trees are, are grafted pieces off this ancient tree. It's been propagated many times since it died in 1965, the original tree did pass away at over 140 years old.

Warner: Where was it planted?

Skogerboe: It was planted in Jeromesville, Ohio on the farm of Roy and Dorothy Funk at the time that I got the cuttings.

Warner: Wow. I think of Johnny Appleseed as such an integral part of American history, of even my childhood. He planted lots and lots of apple trees.

Skogerboe: He sure did. People often think that he went all the way to the other side to the Pacific Ocean, but no, he never did. He started in Leominster, Massachusetts, and then as a young man, he went with his brother to Western Pennsylvania, which at that time was the frontier around 1800. And then when Ohio opened up their territories for pioneers and settlers, they had a much better plan for homesteading. And according to Ohio law, they had to plant apple trees within five years of staking their claim.

So he went to Fort Duquesne, which was near modern-day Pittsburgh, and just spent days picking the seeds out of the pumice that they had turned into apple cider. And then went down the Ohio River into the river that went north into Ohio proper and started planting apple seeds.

Warner: And this is from the last tree he planted?

Skogerboe: It's from the last remaining tree that survived. There are several others that have claims to be a Johnny Appleseed tree, but this is the only one that has been verified by historical documentation and from apple experts of the time.

Warner: Why was finding this particular apple tree so important to you?

Skogerboe: I have a degree in horticulture from Colorado State, and I had always dreamt of having my own edible nursery. And so I came back to Fort Collins where I wanted to have my nursery and started gathering the plants that were recommended for our area. Many of them just were not available commercially, so I had to graft them.

Cornell University in collaboration with the USDA had a large apple collection. So I went down the list and while I was there, I found the Flower of Kent apple, which was the tree that Isaac Newton was sitting under in 1665, which gave him the idea for the law of gravity.

Warner: Is it possible to keep pieces of that tree alive for centuries?

Skogerboe: It is. Because this branch — even though this tree is five years old — this branch is only one year old. So you take the one-year-old piece and graft onto the roots, and it's one year old again. So you can keep many plants in a state of juvenility through the process of grafting through the generations.

Warner: Now wait, do you have that Isaac Newton tree here?

Skogerboe: I do. I have that tree. It's called the Flower of Kent.

Warner: The flower of Kent. Now, how did you discover that this Johnny Appleseed apple tree was available?

Skogerboe: Well, the only reason I bring up the Flower of Kent is that that made me start thinking about are there more historical trees? And so I started looking for them and I thought, “surely somebody would have these trees in their collection”. But phone call after phone call; “no, we don't have it,” “no, I don't know, you might try this place.” Everything was “no”.

And Johnny Appleseeds’ trees were seedling trees. And apples often resort to being wild trees. Not that their fruit's not valuable, it's still valuable, but modern people want to have the apples that taste delicious. And Johnny's trees weren't necessarily that delicious.

Warner: Oh wait, Johnny Appleseed’s apple trees weren't necessarily that delicious?!

Skogerboe: No, they weren't. They were useful. They were sweet, but maybe they were mealy. Maybe they were good just for apple cider or for baking or for feeding cows and pigs.

Warner: Aha. And so I imagine that that made these trees less desirable and maybe more elusive for you.

Skogerboe: And that was the other thing too. They're very elusive because at the time of the pioneers, there were just a few settlements, and now Ohio's got this grand population. So the old orchards at the edges of the village are now neighborhoods.

Warner: I see. So these trees, these original orchards, wind up kind of fading into the background and becoming really difficult to find. But you mentioned a woman who had found them.

Skogerboe: Yes. So my wife gave me a book. It was called The Book of Apples. And in there, there was one paragraph about Johnny Appleseed, and it said that there was one tree still alive in Ashland County, Ohio as late as 1961. And so that was my lead.

My mother was a librarian. She told me, “Scott, if you're going to try, the smartest person in town is usually the reference librarian because all they do is read.” And sure enough, I called the reference librarian at the Ashland Library and she said, “Hold on, let me get the file out”. And she had kept a file on Johnny Appleseed because he lived in Ashland County. And in the file, there were notes which said that that tree had died in the mid-sixties. And I was kind of devastated, heartbroken, all my hard work… gone. But I asked her, “Do you know whose farm it was on?” And she said, “Yes, it was on the farm of Roy and Dorothy Funk, and I think they're still alive.”

She got the phone book out and gave me the phone number. I called up the number and Mr. Funk answered the phone, and he was very old. I introduced myself and told him I was looking for the tree of John Appleseed. And he said “Hold on a moment. Hey, Dorothy, get the scrapbook out. There's a young fellow who wants to know about the John Appleseed tree.” And I asked him if anybody ever took cuttings. And he said they did. I can imagine him thumbing through the scrapbook, and he said, “Here it is. Some school children from Brunswick, Ohio came down to visit the tree on a field trip, but they're the only ones who did it.” So that was my big lead.

So I called up the Brunswick School District, and this was the early nineties, so from the early sixties to the nineties — that's only 30 years. So the teacher could very well still be alive. And sure enough, I found the teacher. She could not remember the name of the student, but she remembered the man who received the cuttings, and his name was Bill Ison. He was an orchardist and had an apple bakery. He turned the apples into apple pie and he had the tree still.

Warner: What a story! And it makes me think, gosh, that every tree I pass has a history too, has a family tree, for lack of a better term.

Skogerboe: Right? The thing that I always remembered from this is that the reason why the school children had gone down to visit the tree was because it had appeared in the front page of the Cleveland Plain Dealer newspaper. And the headline was: “The Last Remaining Tree of Johnny Appleseed.” And so of all the people that read that newspaper article in 1961 — they could have gone down, the Ohio State University professors could have gone there, apple nurseries could have gone down and gotten cuttings of it —

Warner: But it was school kids!

Skogerboe: It was a seventh grader. A seventh grader had saved that tree from being lost forever. The last tree of Johnny Appleseed.

Warner: Is Johnny Appleseed, to some extent, an inspiration for you?

Skogerboe: Johnny really has been. When I think about his life and how he would give away trees in exchange for hospitality, that is an inspiration to me. And I work for a profit-making nursery, and that's necessary. But I always have felt that if someone really wanted a tree and it was something that I had, I would give it away. In the spirit of veneration for Johnny Appleseed, when I first received my cuttings, if anybody ever wanted it, they got it. A big nursery in Oregon called Raintree asked for cuttings, and I just sent some to them. The owner asked, “What'd you want in return?” And I said, “Nope, it's for free.” So he in turn sent me a gift certificate. I didn't ask for it. It’s sort of like paying it forward, and that's how it worked.

Warner: I was reading up on Johnny Appleseed just because I knew more of the myth in a way, or the lore, than the man. He was vegetarian?

Skogerboe: Yeah, Johnny was an interesting man because he believed in non-cruelty. He didn't believe that grafting was even something he wanted to do because he had to cut the top of the tree off — he didn't believe in it. That's why he believed in planting seeds.

Warner: Tell me about the elm tree on this property that's connected to George Washington.

Skogerboe: Oh, that's a locally famous tree. George Washington, after [the Battle of] Bunker Hill — which started the Revolutionary War against Great Britain — rushed to Boston and signed into existence the continental army where the British were bunkered down in Boston and Cambridge was where the Americans had control. So that tree got to be known as the Washington Elm.

Warner: And he sat beneath it?

Skogerboe: He sat beneath it and signed it into existence under the Washington Elm at his headquarters in Cambridge. And as the tree got older, the tree started to decline. By 1920, the tree was nearly dead, but the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution propagated the tree and then sent it to the various chapters of the DAR. And one of the trees survived still to this day in Loveland, Colorado. And was at a school, but now the school's been torn down and there's a Walgreens there, but the tree is being protected by barriers so that cars don't smash into it.

Warner: But you have one here?

Skogerboe: From 1920 to when I propagated, the tree was 90 years old. And I thought, oh, that's worth propagating. And I took cuttings and it roots fairly easily, so I propagated it and I gave them away. So George Washington High School in Denver, there's one on their grounds there. And then there's another in Colorado Springs — I gave one to Fort Carson’s army base down there. I don't know if theirs survived or not, but it could well still be alive, but we have ours right in this field still.

Warner: The notion that there is a tree connected to George Washington that's next to a Walgreens in Loveland is a bit of a contrast. Scott, I want to talk about your passion for horticulture, your own history, if you will. Your dad helped you develop that, correct?

Skogerboe: My father was very interested in gardening, and same with my mother. My mother actually surpassed my father. But back in those early days, my mother was busy with four children. I started planting vegetable gardens and then flower gardens, and became very much interested in horticulture. I studied it straight out of high school at Colorado State. But I didn't finish that time, and that's why I ended up in the army. Because when you don't finish a college degree, it limits your possibilities.

Warner: When you were in the army, is it right that you used to save the cores of apples that you and your family ate?

Skogerboe: I certainly did. On my first day in the army, I woke up and realized where I was, I was like, “Oh, no, what have I done?” But that's when they are really hard on you in basic training. But I had decided that once my four years were over, I wanted to get out and go back to horticulture. So I started reading all these books on horticulture, and I wanted to teach myself how to graft. And after several years, I found myself in Belgium at NATO headquarters, and we rented a house from a Belgian family, and they had 50 fruit trees in the backyard. And so I said, I'm going to teach myself how to graft. But I had no root stocks. I had no pots. So I saved the apple seeds out of my cores. I saved my half-gallon milk cartons for the pots, poked holes in the bottom, figured out how to grow the root stocks, and planted them in my milk cartons. And then the following year, I went and started propagating the trees from the backyard. And fortunately, I think my life would have been completely different if I had failed, but about half of them made it.

Warner: And they're probably still growing in Belgium.

Skogerboe: Oh, they certainly are. So the next year I did that, but instead of six, I did hundreds of them and I went to all my neighbors and gave them away. And the ones that I had left over, I went to the hospital and made an announcement over the intercom. And because at the time, NATO had 16 different countries — all these Europeans came pouring out from Germany, France, the Netherlands, and the UK — I could name them all, but just to save some time. They all took one. But there was a particular officer, he was a doctor from Germany, and he said, “Sergeant Skogerboe, how long will it take before these trees will bear fruit?” And I said, “Oh, sir, probably five years or so.” He goes, “Oh, I won't be here by then.” And I said, “Well, we have a saying that I've read that a man has at least made a start at understanding the meaning of life when he plants a fruit tree, knowing that he may well never sample the fruit.” And so the officer said, “Hmm, good point. I'll take one.”

Warner: Trees as legacies, Scott, trees as legacies. How all of this will live well beyond you.

Skogerboe: Right. That's the thing about trees: they can live for centuries. That Flower of Kent apple tree from Isaac Newton? It's still alive. And it was alive in 1665. By 1815, the tree had been preserved because of its historical significance. But a storm came through England and blew the tree over. And any other tree that wasn't historically significant would've been turned into firewood. But no, they just let it stay. It was still alive and the trunk was now laying on the ground and in rainy old England, the trunk rooted. And now that tree is young again.

Warner: I like that the lesson of gravity happened several times with that tree, didn't it?

Skogerboe: Good point.

Warner: You said early on that you wanted an edible nursery, and we drove up a dirt road just north of Central Fort Collins onto your wholesale nursery. What was the importance to you of it being edible?

Skogerboe: Well, this nursery was not the one I originally started. That nursery was edible, but it failed. I had gone and learned part of my craft here, at this nursery, while I was in college. This is a well-rounded nursery, Fort Collins Wholesale, we grow over 400 different types of plants from edible plants, small fruits, ornamental trees, evergreens, we grow everything. And our nursery here is one of the few nurseries in the state of Colorado where we will grow, for instance, an oak tree starting with an acorn. So we start from the very scratch. And so in this greenhouse, there's probably a hundred thousand trees and shrubs that we've all started from trees, cuttings or grass. But when I came here, because I came from my love of edibles, I brought a lot of my plants along with me. And so we have a big line of grapes, currants, cherries, and apples that now can be bought throughout the Rocky Mountain region

Warner: Back to the Johnny Appleseed apple. How long before these bear fruit? Am I going to be alive?

Skogerboe: Yes, you will be.

Warner: Okay, good. And they're not going to be that good. Have you tried a Johnny Appleseed apple?

Skogerboe: Oh, I certainly have. Bill Isen, in Ohio, who had received the cuttings from the seventh grader in the early sixties. I asked him if the fruit was any good. And he said “Well, I suppose it is.” I asked him, “Is it good for fresh eating?” He goes, “Oh, heavens no. It's really good for chucking at cats.” And so I am not cruel to animals. I've never tried. I never will. I love animals, but I did try the fruit, and it is not as bad as that. It's got a sweet flavor. It's crisp, it's crunchy, it's just bland. It's kind of like a red delicious, but blander, if you can imagine that.

Warner: We'll have to try one someday from these cuttings. What do you say?

Skogerboe: Okay, deal.