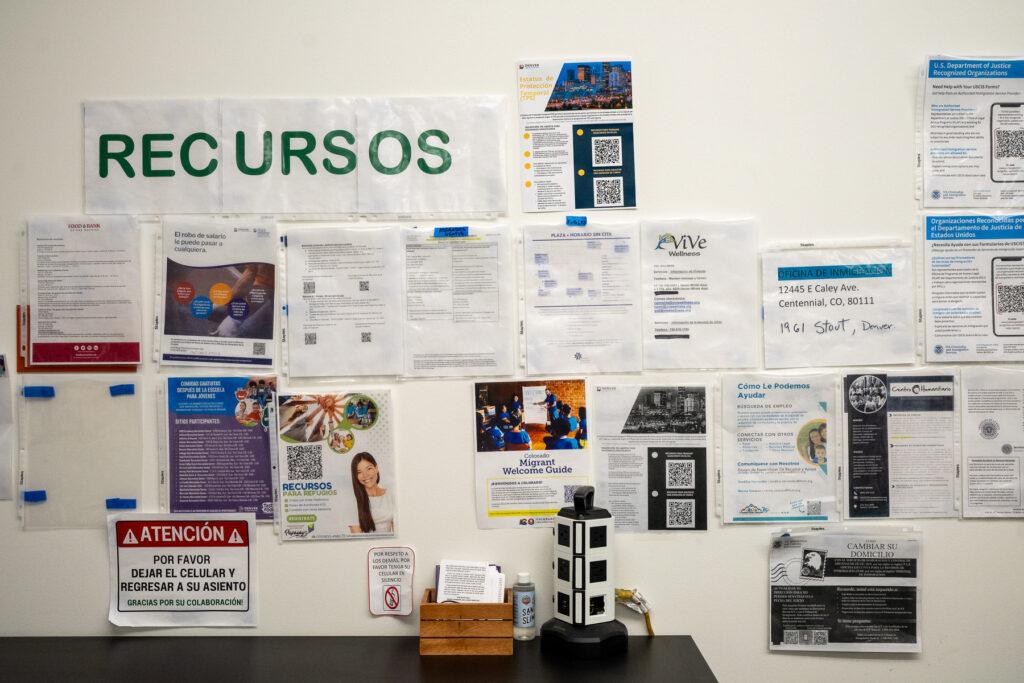

In north Denver, the city operates a reception center set up to manage the arrival of an influx of newcomers. Many come from across the nation’s southern border, driven by dire economic conditions, political unrest, and violence.

A trickle of people check in. City employees, sitting at laptops, ask them questions in Spanish. Some carry or roll a bag or two. Boxes of donated shoes and clothes line the walls. The traffic has dramatically eased for reasons that aren’t clear.

“There's not many people here right now,” said Jon Ewing, Denver Human Services spokesman, who noted in December 2023 the city received 144 busloads of new immigrants, many sent here from Texas. “What we were seeing weeks ago was 200, 300 people a day arriving in Denver. We were seeing lines out the door, lines out the building even.”

Though the numbers have dropped, Ewing said roughly 20,000 new immigrants are still living in the metro area. In any population of that number, some will have a cold or the flu. Others will struggle with chronic conditions like diabetes or heart disease. Some are pregnant. Some are kids. On top of medical needs, these new immigrants have also endured a long, tough voyage.

That’s the story now, as Coloradans and the state's health system step up to help provide care for an unexpected rise in the number of new immigrants in the last year.

That includes places like clinics and hospital emergency rooms, where the extra people put a strain on staff and resources.

One recent arrival to the welcome center spoke through a translator, explaining that his name is Oscar and he's 19. He wore a baseball cap and striped Samba soccer shoes and had a couple of bags.

Oscar, who didn't give his last name, said he's from Colombia. He traveled for three months by foot, by bus, and then by train, including crossing a dangerous jungle through Panama to get to the U.S.

“Yeah, it was really, really hard,” he said. “Muy difícil.”

He came to Denver via New York. He said he used to cut hair, showing a trimmer in his bag. He left his family in Colombia because it wasn’t safe there. Now he said he wants to study, wants to work.

If you don’t work, you can’t eat, Oscar said in Spanish.

‘They’ve been on a long trip’

In the last 15 months, the city has seen 40,000 new arrivals. While many have moved on to other places, about half have stayed, putting a strain on services.

“By the time they get to us, they're totally exhausted,” said Dee Dee Gilliam, a public health nurse with the Denver Department of Human Health and Environment. “They're starving. They're dehydrated because they've been on a long trip.”

Gilliam said new immigrants are first provided with food and water. Then newcomers get quick health checks with key questions. So far 5,000 people have been screened.

“We're looking for the respiratory diseases,” she said. “We're looking primarily for symptoms of covid or flu. The skin diseases we're looking for are Mpox or varicella or measles.”

So far, no cases of highly contagious measles have popped up. But DHS spokesman Ewing said the city recorded more than 600 cases of chickenpox during the last year or so, with an outbreak of 150 in January, after a sharp cold spell.

“When you have that many people in shelter and you have the cold that is keeping them all together,” he said. “It's just more likely to spread.”

Newcomers are offered vaccination options when they arrive at the reception center, said Ewing. Those include varicella, TDap, MMR, flu, COVID-19, and meningococcal vaccines.

Since January, Ewing said providers vaccinated 90 adults and 84 kids at the reception center. Newcomers can also receive vaccines at public health clinics as well.

Mayor Mike Johnston has described the city as facing a "tornado," with a pair of crises: homelessness and dealing with the arrival of new immigrants.

Support for new immigrants has cost the city more than $42 million; that’s on top of more than $48 million spent on the House1000 campaign to bring more than 1,000 people from the streets into shelters in the last half of 2023, according to Denverite.

Seeking better health care

At the reception center, drawings made by visiting kids are hung behind a table where some nurses sit. Cortney Peters, a public health nurse, said some arrive at the center with specific needs.

“A lot of them are really here to seek better health care. And some of them have come and their medications have been taken at the border,” she said.

The ACLU, working with partner organizations, reported in February that medication and medical devices are among the items routinely confiscated by Border Patrol as new immigrants cross the southern border.

The sicker patients arriving in Denver get referred to emergency rooms, urgent care, and clinics.

“The volume of patients has increased significantly. It's good that we have this new building with the increased capacity,” said Jim Garcia, CEO of Tepeyac Community Health Center, which cares for the medically underserved, like the newcomer population.

It recently built a new building, tripling its capacity. That’s helped as volumes and wait times have gone up. Garcia said wait times for uninsured, new patients increased from about six to seven weeks in October to 12 weeks now.

Often the new patients who’ve immigrated don’t know anyone in Colorado, can’t pay and government reimbursement is uncertain.

“They're coming with even less support and resources than your typical immigrant family,” Garcia said.

The sentiment is echoed by the volunteers working with the new immigrants. Grassroots groups have scrambled to provide food, clothing, and transportation for new immigrants, many packed in hotels.

“Oh my gosh, it's really, really difficult,” said Lydia Flynn, one of more than a thousand volunteers who’ve stepped in to help. She said seven groups have formed, including the one she’s with, NE Denver Community Outreach.

Health care is a hurdle, she said.

“I've been quite concerned about the new moms. I met a mom the other day who was actually 37 weeks pregnant,” she said. “But she looked like she was probably four months along.”

Moms’ diets are not good, so many newborns are underweight and end up in pediatric intensive care, Flynn said, adding many need mental health help too.

“We have families dealing with domestic violence, anxiety, and lots of depression.”

Late in 2023, many children, coming from warmer climates, had colds and flu-like symptoms. Not knowing what to do, volunteers took people to Denver Health.

“Just to get basic health care needs. I mean, none of us are doctors, so the best thing we could do was go to Denver Health,” she said.

A strain of additional patients

Denver Health is the state’s main safety net hospital. It cares for patients regardless of their ability to pay. It’s a big job these days.

“Our estimates are that we saw about 8,500 patients from those countries who were new to Denver,” said Dr. Steve Federico, a pediatrician and its government and community affairs director.

That was in 2023. That drove up its ER visits by 10 percent in the fall and early winter, putting more pressure on staff.

“That's really the story in terms of where the strain is,” Federico said. “It really has to do with additional patients that perhaps we weren't staffed for, that we weren't planning on seeing.”

The demographics of the new arrivals have changed over the last year, from more young adults to more families. Denver Health delivered more than 100 babies in that time, which isn't surprising given the number of people coming to Denver.

“That poses additional moral strife in terms of thinking about, ‘Well, what's going to happen to this family with a new baby now out in our community?’” Federico said. “When, as the city has pointed out regularly, it's increasingly hard to respond to the numbers in terms of social needs.”

And of course there’s a financial cost: $10.5 million to treat those patients in 2023, Federico said.

The hospital provided $140 million total in 2023 in uncompensated care. So caring for new arrivals comes as the hospital already faces rising costs and low reimbursement from government programs.

“I don’t see a path forward where the public is not helping us significantly to fund our mission moving forward,” he said.

Back at Denver’s welcome center, three more people arrived. They had to deal with government paperwork after losing key documents in transit.

Thirty-seven-year-old Lorena, who just gave her first name, said in Spanish that she cleaned houses and did nails. But the economy in Venezuela took a nosedive, that’s why she left.

Through tears, she explained she left behind four children, three teens and a 10-year-old, because of the economic situation. She was unable to afford food for her family. She had been living in a shelter and getting money from recycling cans. After she got to Denver, she developed a severe problem with her kidneys.

At a shelter where she was staying, she had horrible pain and wound up hospitalized. Now, Lorena needs to see a specialist but is worried about the cost, she said through a translator.

“She doesn't want to go again to see the specialist because she's aware that it is going to increase her debt to the hospital,” said the translator. Where did she go to get care? “She went with Denver Health.”

Navigating both her health and medical bills will be an ongoing challenge for this new immigrant and the city where she now lives.

- Why Colorado isn’t a ‘sanctuary’ state despite its strong immigrant protection laws

- A beloved Arvada garden center hired new immigrants with work permits. Then came the anti-immigrant blowback

- Colorado Springs says it’s not a ‘Sanctuary City,’ but local nonprofits want to help new immigrants anyway

- Cities across Colorado rush to counter rumors of supporting new immigrants