Should you ever lose control while skiing at 130 miles per hour, be aware that the friction between the snow and the mass of your body sliding downhill is enough to melt the material of your suit into your skin. While you wait for gravity to slow you down, you’ll feel the heat begin to weld synthetic and organic material together. Don't try to adjust your body at that point because something worse could happen. Just ask speed skier Ross Anderson, one of the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame's latest inductees.

“When you're falling on the snow, you feel that intensity of that heat on the leg, but yet you don't want to move. You don't want to try to stop yourself because that will end up being more dangerous as far as getting something broken or even worse than that and that's what you don't want to do,” Ross Anderson said.

Anderson still remembers that 1998 crash in the French Alps, as well as the doctor who had to separate his leg from his speed skiing suit afterward so he could try again to test the limits of human velocity on skis.

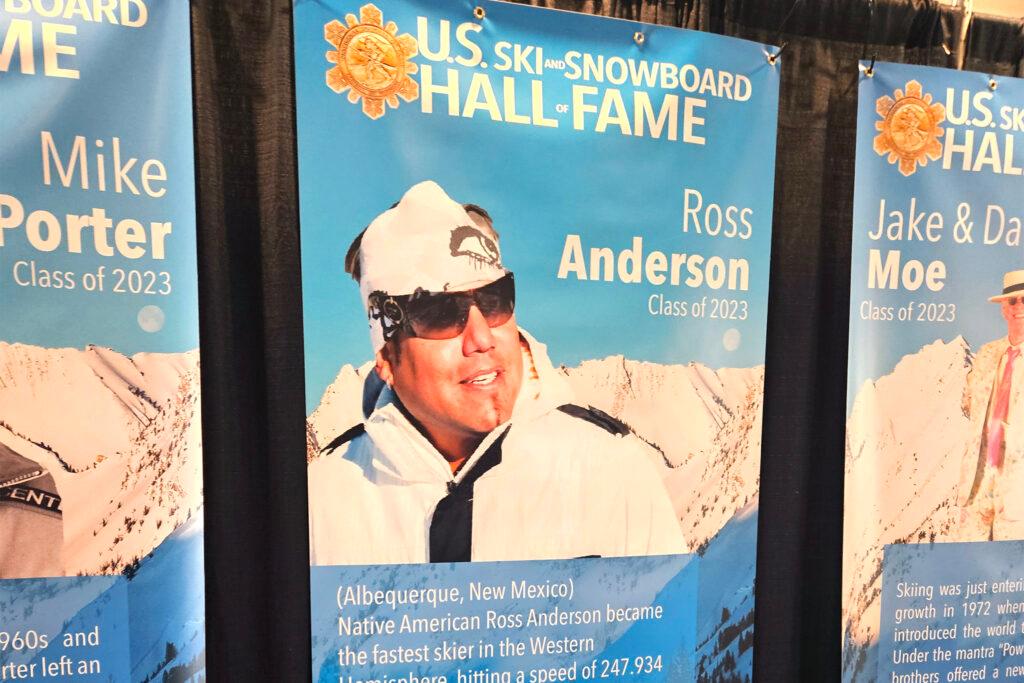

It’s one of the many stories that dot a skiing career that began at Purgatory Ski Resort outside of Durango and which will be recognized on Saturday, March 23 with his induction into the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame.

Anderson, who is Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Mescalero-Chiricahua Apache, still holds the American speed skiing record at 154.06 mph, which he set in 2006.

Speed skiing involves straight-lining directly down a steep pitch with no obstacles, turns, or tricks to obscure momentum. It’s a blend of aerodynamics, courage, and strength all crammed into a specialty suit and helmet that Anderson hated wearing.

“Terminal velocity is 123 miles per hour. We're going faster than that — and that's a person falling out of a plane, just free falling — so imagine that and me whizzing by that person that's just free falling at 154, compared to 123,” Anderson said. “It's definitely a sport where you definitely have guts, but you also have to have the ability to be very advanced in your mind, your body, and spirits. Everything has to be working 100%, without a doubt, when you do this to us.”

Anderson, who now lives in New Mexico, grew up doing more traditional ski racing in Durango.

“(My family) always knew when I was little that I was a speed demon back in the day,” he said.

Anderson eventually grew into speed skiing, which would take him all over the world. In Europe, he regularly drew the curiosity of children who’d never seen a Tribal citizen before.

“I was really impressed with the Europeans because they read about the West. They had books about that era of the Natives, so they actually knew about the history about Native Americans,” Anderson recalled. “So they knew about it, but they were very curious to the point that a lady with her son was there and the son kept pulling on her pant legs, asking in French, ‘Where's his horse? Where's his horse?’”

At the time, Anderson said he was more focused on his craft than what his place in history might be, although that did eventually come. Anderson said he’s particularly charmed that he ended up in a McGraw-Hill mathematics textbook as a part of a word problem.

“For me, it was like a seed of a tree where you plant it, you nourish it, you grow it, and for me at that time, it was just about growing it, going straight up to the top,” Anderson said. “Well, you don't realize that you're going to have branches. Those branches are different things that you created or you worked with or you developed: my kids' programs or your speaking engagements. Being in books for kids to look at and read about — being (in) a mathematics book to be a mathematics problem. I mean, I never realized how much, especially now when I look back, how much my tree had a lot of branches.”