The wind in Trinidad, Colo. can be so relentless, it’s a wonder anything stands for long. But Temple Aaron has lived at the corner of 3rd and Maple for 135 years. And on Saturday, a hearty crowd stood just outside, in gusty conditions, to celebrate this small brick synagogue.

“Very few people are aware of the history,” said Sherry Glickman, vice president of the temple board who schleps from Denver to Trinidad to attend events like this one. “People don't know that this was a thriving community, let alone a thriving Jewish community, but the Jewish population was prominent. They were leaders of the community in the late 1800s.”

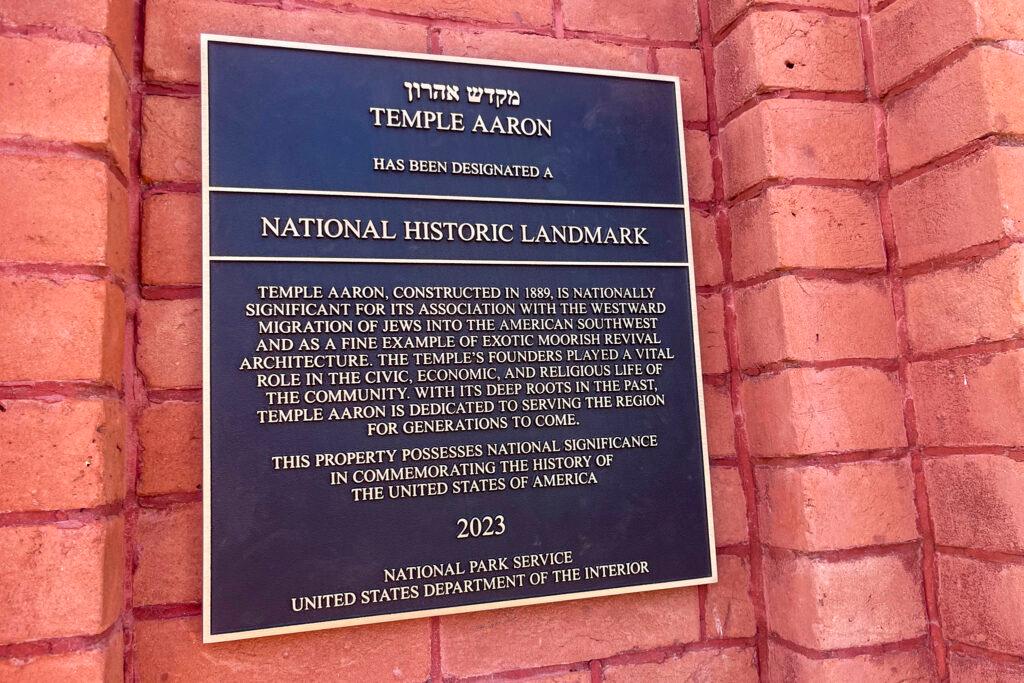

This tenacious temple is Colorado’s newest National Historic Landmark, along with Wink’s Panorama, a former vacation spot in Gilpin County for African Americans who were unwelcome in so many other places during segregation. Landmark status is the strongest historic protection the federal government extends. There are just 28 such sites in Colorado, including Red Rocks and Bent’s Old Fort.

At Saturday’s ceremony, during the Jewish holiday of Purim, Jews and non-Jews alike came from as far away as Albuquerque, Fort Collins, and even Los Angeles to bask in the glow of Temple Aaron’s stained glass and to see the historical plaque unveiled. The plaque reads, in part, that this house of worship is “...nationally significant for its association with the westward migration of Jews into the American southwest.” German Jews in particular came to become merchants along The Santa Fe Trail.

Today Temple Aaron has 1500 supporters and 80 member-families from all over the country, according to Glickman. Services are infrequent, but a monthly Torah study takes place via Zoom, she said.

The unveiling of the plaque Saturday drew Jewish leaders from around the state, as well as Trinidad’s current and most recent mayor, park service officials, and Colorado preservationist Dana Crawford. An armed guard stood watch — a reminder of mounting antisemitism worldwide.

At an earlier Shabbat morning service inside, there were calls to free Israeli hostages still held by Hamas and pleas for peace in the region.

At the unveiling outside the temple, the crowd focused on celebrating the synagogue and what it has meant to Trinidad.

Former educator Olivia Bachicha, who has lived in Trinidad all her life, used to bring her students to Temple Aaron as they studied Judaism and the Holocaust.

“Such a feeling of pride and joy to have such a beautiful synagogue in our community,” she said, beaming. “And I'm so excited that it's finally going to get on the national registry.”

With its idiosyncratic pipe organ — several keys don’t work — and incandescent brass light fixtures, Temple Aaron was almost lost to history. Maintenance costs and dwindling Jewish communities in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico forced its caretakers to put it on the market in 2016. Preservationists at one time considered it among Colorado’s most endangered places.

“It could have been torn down despite the spectacular architecture, so it was uncertain and it was precarious,” said Temple Aaron board member and retired historian Kim Grant as he sat in a creaky pew.

Word of the shul’s potential demise spread and people — both Jewish and not — from far and wide rallied to save the house of worship. Their work continues. The roof is original and needs replacing, for which temple boosters are now raising money.

Brothers Randolph and Ronald Rubin were among the roughly 200 wind-whipped attendees Saturday. For them, Temple Aaron is not distant history. They prayed and played here as children growing up in nearby Raton, New Mexico.

“Our mother would drive over Raton Pass,” Ronald told the crowd. “We would arrive to sing Jewish songs, learn about Judaism, and experience the joy of being with other Jewish kids, since we were the only Jewish family in Raton at that time.”