Editor’s Note: CPR News has spent months talking with teenagers, parents, doctors, advocates, political figures. We’ve looked through once-secret internal industry documents released by tobacco companies and listened to many hours of city council and legislative debate. What we found is that the conversation about tobacco products, especially flavored ones like menthol, is not only about nicotine’s deadly effects or the impact on local economies. It’s about ethics, optics and equity.

A group of volunteers gathered in a church across the street from the state Capitol on a recent day in Denver.

Teresa Haga-Golasewski from Centennial was there. She showed a family photo. “And here's my mom with her cigarette and there's my nephew and he was little!” she said with a laugh.

In the image, there are perhaps half a dozen people. Haga-Golasewski, 62, noted all the adults are smoking. “I probably wouldn't have smoked, if my mom hadn't smoked,” she said.

The volunteers, organized by the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, came here to talk to lawmakers about cancer and tobacco-related bills, as part of the Colorado Cancer Action Day.

Haga-Golasewski’s story is familiar, especially to those who’ve become hooked on cigarettes.

She’d started at 16, smoking with her friends. “It was a cool thing to do,” she said.

She eventually developed a decades-long menthol cigarette habit, peaking at three packs a day. Haga-Golasewski did quit at 52, but not until she’d developed small cell lung cancer and got pneumonia too.

She needed two rounds of radiation and six of chemo. She now tells people how quitting unequivocally improved her health. She simply feels better.

“Oh yeah, a lot better,” Haga-Golasewski said. “I think I started feeling better once the pneumonia wore off. That was the worst part of it. The cancer fighting wasn't as hard as the pneumonia.”

The benefits of quitting come at any age, no matter how bad your habit

Smoking cigarettes is the leading cause of preventable death in the U.S., taking nearly half a million lives each year, accounting for one in five deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In Colorado, it claims 5,100 lives a year, according to the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids.

Tobacco use is responsible for ill health effects all over the body: cancer, heart disease, high blood pressure, lung disease and blood clots.

It may seem like a no-brainer, but more research keeps backing the benefits of quitting at any age and no matter how bad your habit.

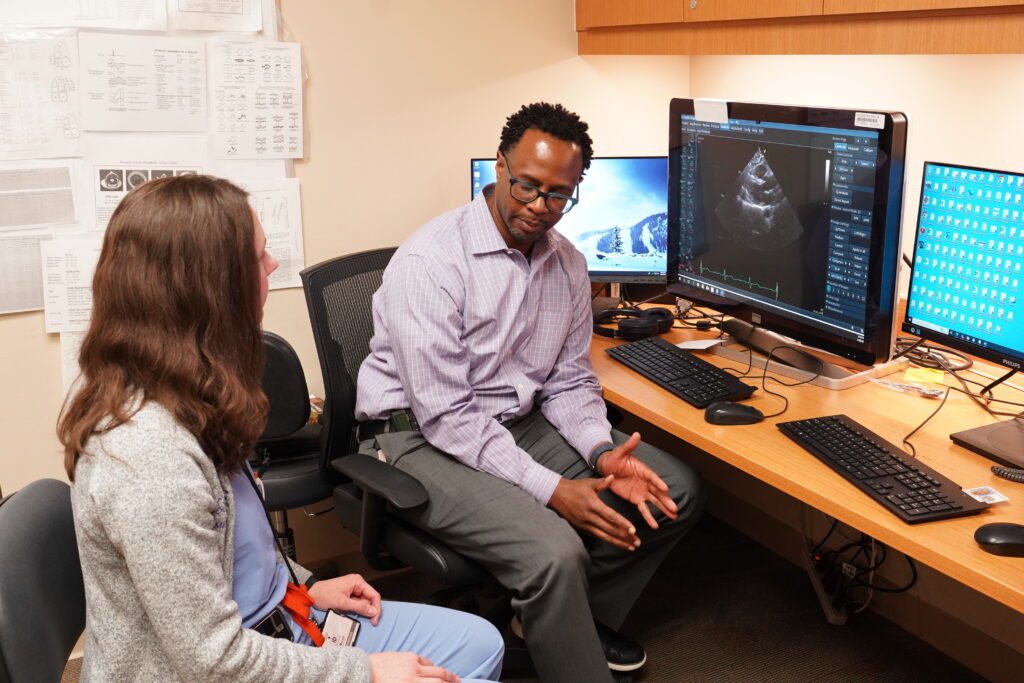

That’s what Dr. Kamal Henderson, a cardiologist, who works with veterans at the VA, tells his patients.

“I tell people all the time, after you have your heart attack, the odds of you dying post-heart attack goes up substantially with smoking,” said Henderson, a former site lead of the Rocky Mountain Regional Veteran Affairs smoking cessation program.

The state's smoking-prevalence rate is nearly 12 percent, about the national average. But in some areas of the state it’s as high as 25 percent among adults.

After you consume your last cigarette, the body starts a series of positive changes that go on for years, according to the CDC. It includes improved health, increased life expectancy, lower the risk of 12 types of cancer and cardiovascular disease, lower risk of COPD, lower risk of some reproductive health issues, and benefits for people who’ve already gotten a coronary heart disease or COPD diagnosis.

The benefits of quitting even apply to those who’ve smoked heavily or for years. The changes play out over years for those who’ve stopped and don’t start again, according to the agency.

Within minutes, the heart rate drops. In a day, nicotine levels drop to 0. Two years in, coughing and shortness of breath decrease and the risk of heart attack drops sharply. In five to 10 years, the risk of stroke decreases. In a decade, the added risk of lung cancer starts to drop by half.

How to quit

Colorado has a number of programs to help people quit smoking and vaping. And the state continues to try new approaches, including using phone apps.

That includes a new push from the CU Cancer Center and its partners. Participants get access to a smartphone app called the 2-Morrow Health Mobile App, which is private and self-paced. It has daily lessons, customized tips and messaging with a live coach.

The Colorado Quitline is free and available to Colorado residents 12 and older and has a website in English and Spanish. Those who use menthol tobacco or nicotine products are eligible for up to 16 weeks of free nicotine replacement products (lozenges, patches, and gum) and $50 in gift cards. The program also has a hotline at 1-800-QUIT-NOW, which is 1-800-784-8669.

My Life, My Quit, is a free, confidential way to stop, offered by National Jewish Health. Denver Health, the state’s flagship safety hospital, offers one-on-one tobacco cessation telehealth visits. Quit programs at UCHealth offer a number cessation classes, support groups and nicotine treatments. Kaiser Permanente Colorado recommends the Quit For Life® program, on its website.

Henderson urges patients and clinicians to talk about it. “So both the patient’s saying, ‘Hey, I want to quit.’ And also the clinician is saying, ‘Hey, do you want to quit?’ So just reinforcing that is very important.”

Henderson uses a two-part analogy: Think of a car. There’s a roadmap to quit. That’s behavioral therapy, talking about how and why you started. And there’s gas, that’s treatment, maybe in the form of nicotine replacement therapy, like patches, lozenges or medications, to stop. Henderson said the combination is key.

“They built a life around this thing,” said Henderson about smokers. “Without consciously and actively trying to understand how their life was built around it, you won't be able to disentangle how to get these things out of your life.”

‘Just keep trying’

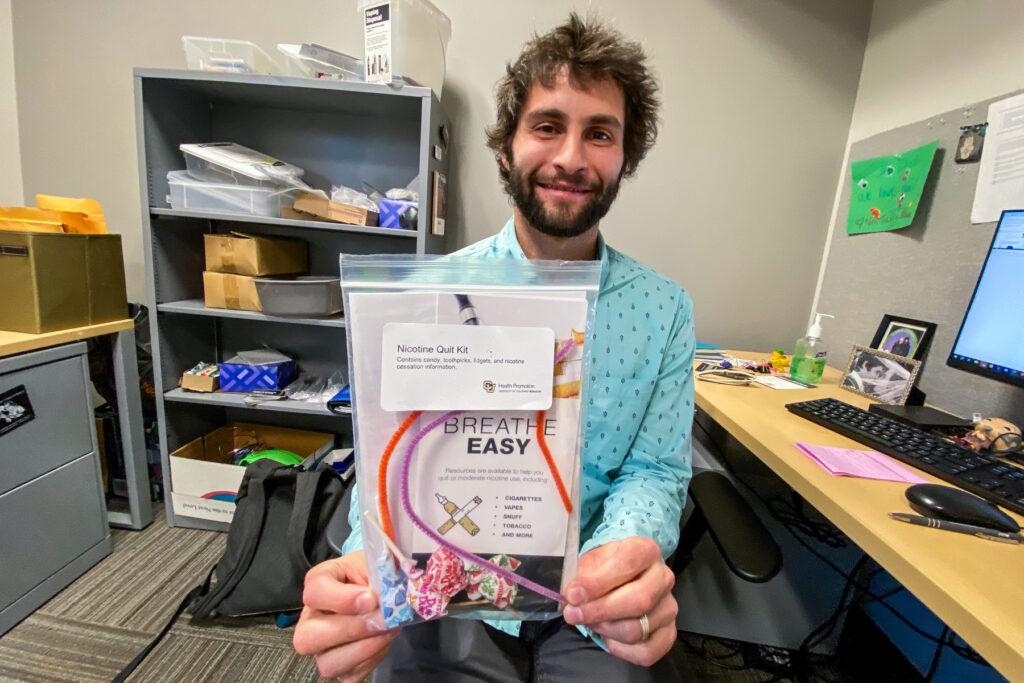

You can hear similar themes up at CU Boulder, where students and others on campus can get help through the Collegiate Recovery Program. In his office on campus, program director Chris Lord showed a quit kit, a packet of items, including nicotine cessation literature to help with quitting or moderating use of cigarettes, vapes, snuff, tobacco and more.

“There’s some little candies, like little lollipops in there,” said program director Chris Lord, holding up the clear plastic bag, which also contains toothpicks and fidgets.

At CU, the issue for many isn’t smoking but vaping.

Coloradans vape at rates higher than the national average. One in six Colorado high schoolers currently use e-cigarettes. And adult vaping rates are rising in Colorado, driven by a sharp increase among young, college-age adults, those 18 to 24, according to data from the state health department.

When people are withdrawing from a nicotine addiction, anxiety and agitation can be triggering. Lord said the aim of CU’s program is to give coping tools, insights into why they began and access to resources, without judgment.

“If you've tried and you feel like, ‘oh, I haven't been able to do it,’ keep trying,” said Lord, whose title is associate director of the Alcohol and Other Drugs Programs and Collegiate Recovery. “Because the people that succeed are the ones that just keep trying. That's just how it works.”

Recent CU grad G Kumar told me two boxes of awful tasting eucalyptus-flavored toothpicks helped with the oral fixation and cravings for nicotine that come with a vaping addiction when they tried to quit.

“The fact that I could just gnaw on toothpicks for weeks on end was I think what kept me sane,” said Kumar.

Kumar started vaping and later smoking in part to deal with stress, to take the edge off. But it became a crutch. “It's still not super easy, but I'm glad I did it. I've saved a lot of money and I am not beholden to a substance, which feels great,” they said.

Kumar estimates that vaping habit cost about $60 a week, or $3,120 a year, a large amount for any student.

Quitting cigarettes will also save a lot of money. The average cigarette pack price in Colorado is $9.72. So a pack-a-day smoker who quits will save nearly $3,550 a year, according to the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids.

Colorado spends more than $20 million a year on tobacco prevention programs. But that’s half what the CDC recommends. What’s more, the industry spends five times that each year in the state in marketing.

Some state money slated for spending on tobacco cessation and prevention often gets diverted to other health programs.

“Prioritizing other health issues is great, but we could prevent those health issues and that chronic disease by investing in these programs to curb those who are initiating to begin with. And we're not doing that,” said Jodi Radke, with the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids.

The tobacco industry spends more than $8 billion a year nationwide on marketing its products, according to CTFK.

Advocates say investing in cessation and prevention programs bears major dividends.

“We've done a lot here in our state, and I think that there's still a lot to do,” said Sen. Kyle Mullica, a Democrat from Thornton, who is also a registered nurse. He noted Colorado raised the legal purchase age of tobacco to 21 after vaping took off. “But a chunk of that is making sure that we're investing into that and specifically investing in the cessation and making sure that our public is educated on the consequences of using these products.”

Granddaughter’s arrival inspires change

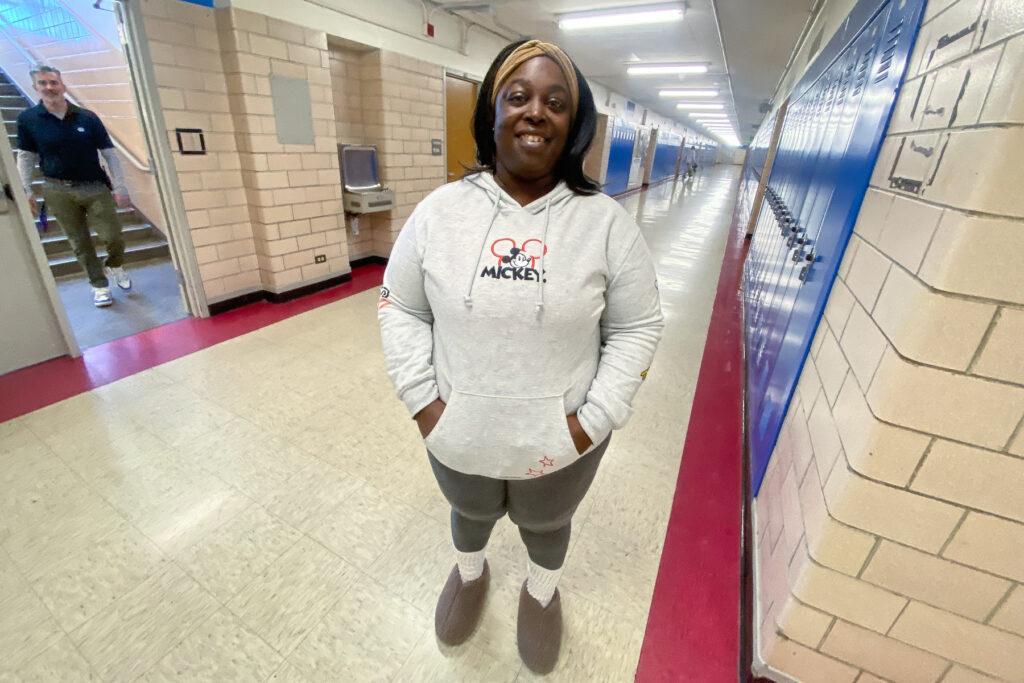

“I quit on March 26th, 2023,” said Denverite Shatoya Harris, a caregiver, who started smoking in her early 20s, when she first tried a Newport cigarette offered by a cousin. In time, she moved on to wine-flavored cigars called Black & Mild.

“I would smoke a whole box and a half a day. And I knew that wasn't good,” Harris recalled, while visiting the school of her daughters, Manual High in Denver.

“My kids even asked me to stop. And I tried to stop,” she said.

Cold turkey didn’t work. It took five years of trying and a new motivation.

“I've tried the patches, I've tried the gum, I've tried everything under the sun and nothing worked,” said Harris, who added that in search of relief she’d chew through bags of ice.

Then her granddaughter Kehlani was born. “I think my grandbaby is what really, really motivated me to quit.”

The benefits were immediate. Her flavored cigars were pricey. So she saved hundreds of dollars a month, thousands a year, she’d been spending on a pack-a-day habit. “Yeah, I could buy a decent car off of that,” she said with a hearty laugh. “Yes. Just by quitting. And I see the difference. I really do.”

Colorado saves people a lot of money on health care when people like her quit. Employers save on medical and insurance costs. Government saves on costs to health programs, so do taxpayers who fund them. Harris said she’ll now save on health costs too.

“My breathing has gotten better,” she said. “I could do a lot more activities with my grandbaby.”

How did she do it? She talked it over with her doctor, who prescribed a drug used to help people quit, called Chantix, the brand name for a prescription medication also known as varenicline. It doesn't contain nicotine, but works in a similar way to how nicotine impacts the brain; it’s what’s called a nicotine receptor partial agonist.

“It just took the urge away,” said Harris, adding the only downside was some weight gain. “So if anyone out there that's trying to quit smoking, I really recommend them to, if they could speak with a doctor.”