Drone footage, taken April 4, 2024, shows crews working to stabilize and reclaim the massive Pikeview Quarry in the foothills west of Colorado Springs. Change video settings for HD. (Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite)

The huge red dirt terraces of Pikeview Quarry have marked the mountains west of Colorado Springs, expanding for more than a century to eventually cover 125 acres.

“Is it like a mining scar?” El Paso County resident Tara Jarvis asked when we stopped her to talk about it at a park not far from the quarry. “A red one, right?”

“I know a little bit about it, but I'm not from here originally," said city resident Ling Li.

Even though it can be seen for miles around, residents differ in the way they think about the Pikeview Quarry. For some, it's not even on their radar. For others, well, Summer Williams was somewhat familiar with it.

“I just know that it looks weird,” Williams said. “I just heard that it was a mine of some sort.”

What do you do with an old rock quarry? It's a question that Colorado Springs needs to answer

Story by Shanna Lewis and Mike Procell

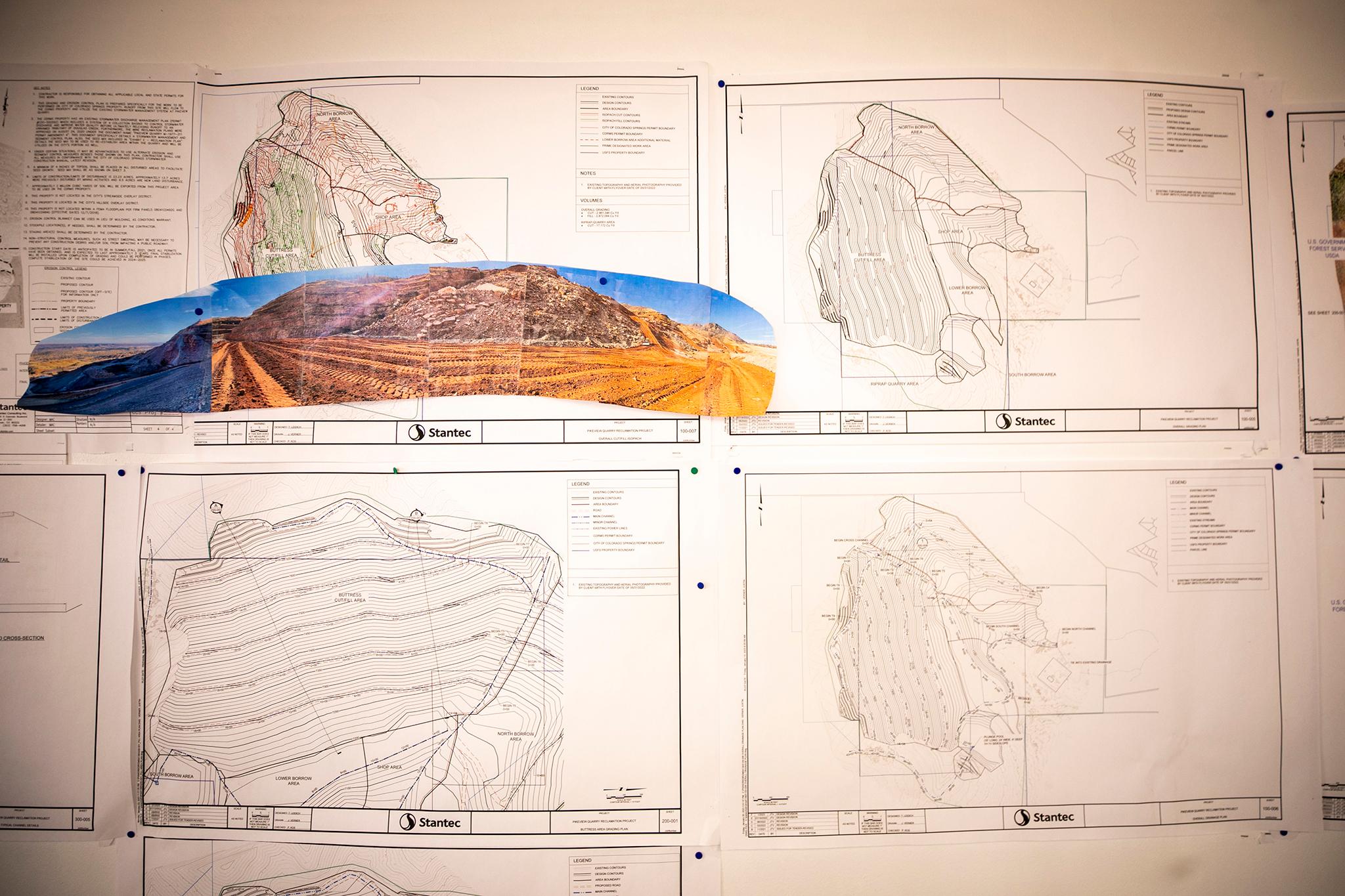

Moving tons of dirt and rock

The scar, indeed, was a mine of some sort. Limestone was pulled out of there beginning in 1903. Now ongoing work to recover the land on the northwest edge of the city is nearing completion, as heavy equipment continues moving lots of dirt and rock around.

Jerry Schnabel has run the quarry for more than two decades for Castle Aggregates, so he’s used to the roar of the humongous machinery that creeps up and down the dirt tracks snaking around the quarry.

“This is a dozer and it basically breaks up the material from what has been deposited there eons ago,” he said, pointing to a machine stirring up a cloud of dust.

Schnabel said in the 1970s, operations at the mine started going deeper instead of wider, causing some minor landslides. Mining continued though, and over time underground water pressure increased, leading to more substantial landslides in 2008 and 2009. That shut work down for about five years.

Image (left): Castle Aggregate President Jerry Schnabel stands atop Colorado Springs' Pikeview Quarry. April 4, 2024.

Mining ended permanently at the Pikeview Quarry in 2018, but efforts continued to stabilize the terrain.

“This slope is finished,” Schnabel said, pointing out a portion of the quarry, “but underneath there is a piece of limestone that was part of the original quarry that’s never been mined. We left that after the slide as a doorstop… And everything that we fill between here and the slope is acting like a wedge.”

Laser beams, young trees, and bighorn sheep are part of the project

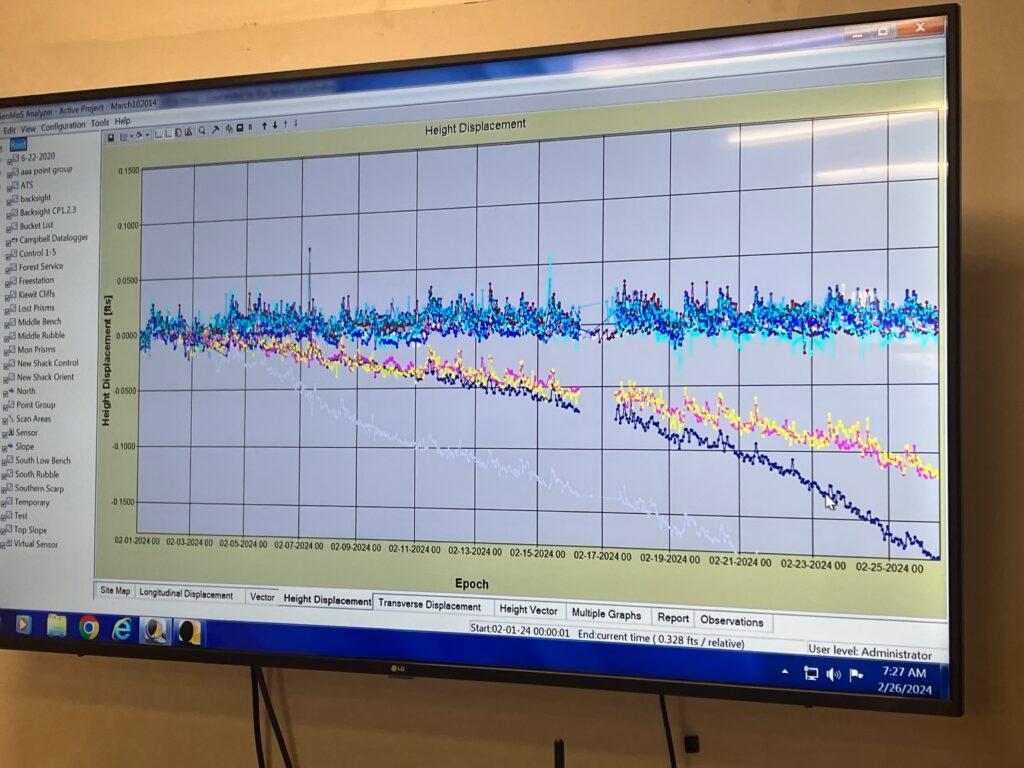

They installed a new monitoring system after the landslides that shoots out laser beams every hour to lenslike glass prisms located around the quarry. They can tell if the ground is moving if the light reflected from the prisms shifts, Schnabel said.

“If one of those moves more than a 10th of a foot,” he said, “we get a call on our cell phone.”

The monitoring reports go to the state Division of Reclamation, Mining and Safety each month. That’s the agency charged with determining when the remediation work is complete.

Planting native vegetation is also part of the reclamation process.

“We're still experimenting with that,” Schnabel said. “The best survivor rate is the smallest trees, the seedlings.”

There’s also revegetation occurring on U.S. Forest Service land adjacent to the quarry that burned during the Waldo Canyon fire in 2012. The quarry likely helped protect some of the nearby neighborhoods during the fire, Schnabel said.

“This was all deforested already,” he said. “It (the quarry) acted like a fire break. There was no way for the fire to come through here.”

Schnabel wants to see the reclamation work also support the large bighorn sheep herd that frequents the quarry.

“We built a watering hole for the sheep after the fire, and it's drawn them in here,” he said. “We are a mining company and people sometimes think mining is kind of anti-wildlife and it's really not. These sheep hang out here, they lamb here mostly, but these guys (the males) came in in the fall looking to fight and breed.”

The sheep are not too bothered by the mining equipment, according to Schnabel, so he hopes they’ll stick around as changes come to the quarry.

The Gidwitz family of Chicago owns the mine. They’re giving the city of Colorado Springs the option to take ownership of the land once the reclamation is finished.

“The city put up with a scar for over a hundred years.” That’s what Jim Gidwitz has said according to Schnabel. Jim led the company that owns the quarry, his brother Ron later stepped into that role and a new CEO took over earlier this year. “The city should have the right to decide what goes forward and he (Gidwitz) kept his word. The reclamation has all been done with private funds. It's all from the family. It's not any public funding.”

Public funds did go to purchase the unmined property in front of the quarry, which is now part of the city’s parks and open space. City Landscape Architect David Deitemeyer is involved in discussions about the future of the quarry property.

“We see progress,” he said as he looked up at the quarry from a nearby neighborhood park. “We see opportunity to change the legacy of Colorado Springs in the skyline, the mountain backdrop.”

A place where the bighorn sheep roam and the mountain bikers play?

Around the same time the mine owners began considering what to do with the reclaimed land, the idea of turning the quarry into a mountain bike park started gaining traction.

Hardcore mountain bikers have long wanted more extreme terrain than what the city had to offer, said Keith Thompson of the Colorado Springs Mountain Bike Association.

“It left mountain bikers to feel like they needed to take measures into their own hands to build trails on their own that would meet the challenge and the level of riding that they wanted,” Thompson said.

The city also wanted to fill that need.

Cory Sutela leads Medicine Wheel Trail Advocates, a mountain bike trails organization in the Pikes Peak Region. He and others have said the quarry is ideal for a world-class mountain bike park.

“A community friendly amenity that appeals to the riders of all levels,” he said, “from expert Red Bull downhill crazy riders to families that want to bring their kids.”

It’s not just the varied terrain that makes it ideal, Sutela said, but the fact that it's already disturbed land.

Image (left): In 2017 FlowRide Concepts, a Colorado-based consultant, was hired by Castle Aggregates to create some design ideas for a potential bike park as a visual aid to discussions about the concept.

The elevation change for the proposed bike park is 700-800 vertical feet, with a southern exposure. It is estimated that the bike park could be used for ten months per year.

Residential concerns

The mountain bike groups recognize there are a number of residents who have serious concerns about what’s going to happen at the quarry, especially how it relates to what the city is considering for the adjacent Blodgett Open Space, which the city expects will be a high use area.

Brian Erickson lives in a neighborhood close to the quarry.

“Will the multi-use trails in the open space actually act as an extension for this world-class bike park?" he asked. "So really we have one big, huge biking area that sort of excludes other user groups or creates hazardous encounters just by the nature of people being on wheels versus on foot?"

Erickson said though that he's not necessarily opposed to a bike park.

“I think it's the right kind of idea to invest in recreation,” he said. “So it's just all about implementation. How does it happen?”

Tim Voros also lives nearby. He's both a mountain biker and trail runner.

In some ways, Voros said, he feels like the quarry is part of the landscape of his home. But he does have some concerns.

“I think there's going to be some challenges for the neighborhood, of course, in terms of the additional traffic it'll bring, and attention to the area,” he said.

But, he said, he supports the idea.

“It'll bring better recreational opportunities, I think, for the whole city and better maintenance to these trails,” he said. “Yeah, I think it'll overall be a positive thing.”

The future of the quarry is far from a done deal

Deitemeyer said even though the city is looking at the possibility of a mountain bike park, they haven't made any decisions yet. He said there’s a lot to consider in this process.

“We would open up that conversation for the community,” he said, “and start to think about how to create a potential hub of activity that is isolated to the quarry site itself and away from the neighborhoods to really minimize the impact to the neighbors that are adjacent to this property.”

Listen to community voices here.

Deitemeyer said the idea of a bike park aligns with the city’s master planning process, if and when the time comes. “We want to ensure that it's sustainable, that it's appropriate in terms of maintenance costs and operating costs, that it respects the taxpayers who help fund it.”

Most of the people who shared their thoughts on the quarry with KRCC said they want the site to be open for public use.

“I just want to make sure that it stays where people can do stuff,” said Jennifer Sharpe who lives within sight of the quarry.

“I think any kind of public use is good for everyone,” said Josh Garcia, who lives on the east side of town.

Many folks, like Ron McDowall, who lives on the southeast side of the city, expressed concern about environmental stewardship.

“Obviously, I’m concerned about the environment,” McDowall said. ”So hopefully any efforts are going to be to protect the environment. I guess if I had my druthers I’d rather see the natural environment intact.”

There are other city residents who are against the idea of developing the property for a bike park and would prefer a natural area dedicated to hiking.

Schnabel said they're aiming for the state to sign off on the reclamation later next year. After that, it'll be up to the city to decide if it wants Pikeview Quarry in its park system and what to do with it.

Story by Shanna Lewis and Mike Procell

Edited by Andrea Chalfin

Photos by Kevin J. Beaty

Produced by Lauren Antonoff Hart