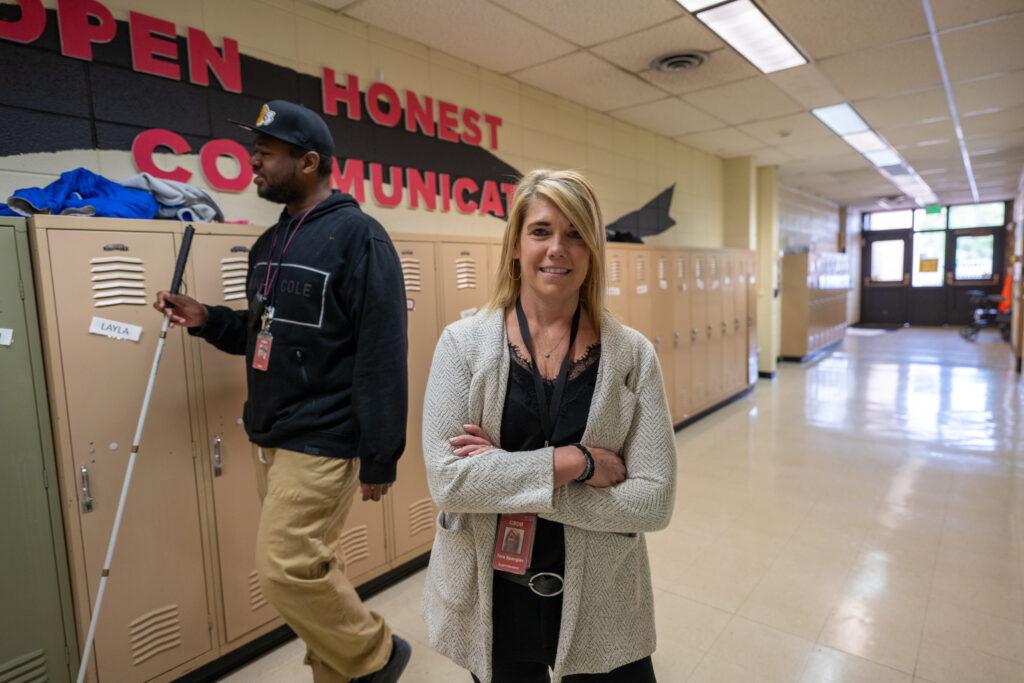

Tera Spangler became the first deaf superintendent of the Colorado School for the Deaf and the Blind earlier this year. It’s a big deal, considering the school was founded 150 years ago, two years before statehood.

The school serves around 700 students, on-campus and statewide, from kindergarten to age 21, and is free to Colorado residents.

Spangler, who is a former teacher at the school, says one thing she wants to continually prioritize during her tenure is for all students to have access to direct communication — something she did not have as a deaf student growing up in Iowa.

Spangler didn’t learn American Sign Language (ASL) until she was in college. She was born with the ability to hear, but after she became deaf at age 10, she says she was “mainstreamed,” and attended school without an interpreter. She says despite her attempts to lip read, she missed a lot of information.

“Even with the hearing aid or the implant, I wasn't getting a complete understanding, a hundred percent of the communication of what was going on in school, not even close,” she said, “I had to fill in the blanks a lot with trying to figure out what people were saying.”

She says her own journey is what inspired her to become an educator for deaf and visually impaired students.

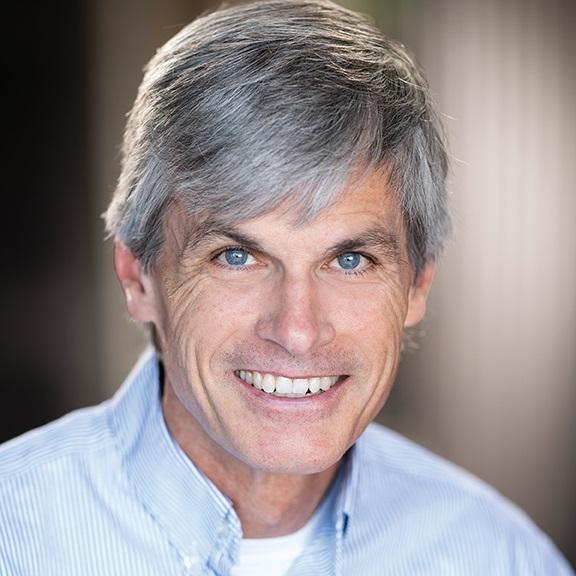

Spangler sat down with Colorado Matter’s senior host, Ryan Warner, and ASL interpreter, Zee Mascareñas, on the school’s campus in Colorado Springs to talk about her plans to boost student enrollment, recruit qualified teachers, and enhance the specialized programs the school offers.

Editor’s note: This interview was conducted with an ASL interpreter. The interview transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Ryan Warner: It is stunning to me that it took a hundred and some odd years for there to be the first deaf superintendent. Do you think it says something about what deaf people face in this society? Is it a reflection at all?

Tera Spangler: I think for the deaf, for deaf individuals, it's actually an accessibility to communication. We always have to accommodate the hearing-people. We don't have enough access to communication using just American Sign Language.

Warner: When you look at the education provided here today, contrast it for me with the education that you received.

Spangler: So I grew up in a small town in Iowa. I was mainstreamed, so I didn't attend a separate deaf-blind school. I think the difference for me was actually to see the communication access for our students. It's direct communication using American Sign Language. For me, I didn't have an interpreter. I was mainstream, so I missed a lot of communication. I missed a lot of information. That is the big difference.

Warner: You were mainstreamed without an interpreter?

Spangler: Yes.

Warner: What did that mean? That they were expecting you to lip read?

Spangler: Yes.

Warner: Does that still happen today?

Spangler: Legally, if the child is identified as a person who's using sign language as their primary language, they are required to have an interpreter. But some parents and some children don't choose that. They don't choose to learn the language. They choose to speak and lip read. So there are still students who don't use an interpreter.

Warner: So that's a choice that families have? And it's a choice that your family made then?

Spangler: Yes.

Warner: Were there ways in which that benefited you and ways in which it didn't?

Spangler: So for me, I was born hearing. I didn't become deaf until I was 10 years old. So I already had spoken language, and I developed that already. I wore a hearing aid and later on I received a cochlear implant, and so I already had some of that, but still, it didn't matter. Even with the hearing aid or the implant, I wasn't getting a complete understanding, a hundred percent of the communication of what was going on in school, not even close. I had to fill in the blanks a lot with trying to figure out what people were saying.

Warner: I don't want to get too probing or personal, but are those conversations you've had since with your family and is it something other families could learn from, superintendent?

Spangler: For me, I do remember there was one meeting. The teacher, she threw out there, “Oh, well, there's an option for you to go to the Iowa School for the Deaf.” During that time, it was two hours away from my house, so I said no. It wasn't something that my parents and I wanted to do during that time. But I learned sign language at college later on and I realized, “Oh, I actually did have another choice. I had another option.” I could have attended the Iowa School of the Deaf, but I didn't realize the benefit until I was actually learning sign language. I then realized that direct communication of ASL.

Warner: This term ‘direct communication’ feels so important to me. You've used this term several times. I wonder if these are students who, to some extent, feel isolated and then come to feel that they're part of a community. It's really important for folks listening to understand deafness is not purely a disability. Deafness is a community. Deafness is a way of life. Deafness is a culture. But that means you have to be around other people experiencing deafness, right?

Spangler: Yes, absolutely. It is a culture. Some of our students — especially some of our students who come to CSDB when they're a little bit older like those in middle school or high school — and they’ve been in public school and they come here later, they are just shocked. They are amazed. “Wow, how can I communicate directly with my peers? I don't have to rely on an interpreter.” They can socialize emotionally. They have the support here. So it's so important.

Warner: How do you think your career is an effort to change that? To make the path easier for younger people than you had it?

Spangler: When I was growing up, I was always aware that I wanted to become a teacher. When I started college, my major was general elementary education. And I realized that was challenging for me. I couldn't understand what elementary school students, what they were verbally saying when they were speaking to me. So one day, my sister, she gave me a tip, “Hey, why don't you consider teaching the deaf, teaching deaf students?” So really at that point, it really hit me. I could have a bigger impact for deaf students, so I shifted to deaf education.

Warner: I'd love to give Coloradans a sense of this place. You have 700 students enrolled. What classes, what sort of learning is going on here this week? I'd love a grasp of this scope for folks.

Spangler: We have about 170 students who are here on campus. They go to school through kindergarten to 21. Actually, their days are very similar to any other student who's attending school. They have reading, writing, math, science, social studies. We have all of those academic areas. We have other specialized services. For example, we have American Sign Language classes, speech therapy, occupational therapy, physical therapy, school counselors. We have blind students as well. We have orientation and mobility classes, we teach our blind students how to use their cane, how to navigate their environment, braille instruction, independent living skills, daily things like cooking or laundry.

Warner: How much does the community of Colorado Springs play a role in those applicable life skills? I wonder to what extent the school feels a connection to the living classroom of a city.

Spangler: Here at CSDB we have many business partners, sponsors for our 18 to 21 year olds. They're a part of our Bridges to Life program. The students get jobs in the community working at the bakery, at an auto parts store. We've had students working at UCCS, working down at Fort Carson. So there's a broad spectrum of things that we try to look for and find jobs and placement for students based on their interests.

Warner: I have to imagine that that has something to do with the unemployment rate in the deaf and blind communities. Is that a fair assumption?

Spangler: Actually, that's our goal. So when students leave CSDB, they can go to college, they can get a job.

Warner: You have been a teacher here for some time, 18 years. What do you want to achieve as superintendent?

Spangler: I would love to see more students, to increase our student enrollment. I would like families to be aware that CSDB is an option for their child.

Warner: What do you think is a block to that awareness? I do know that, I don't know if it's dwindling enrollment, but that there have been enrollment issues. What do you attribute that to?

Spangler: Parents have options. They have options in the state of Colorado, which means that more and more families choose to place their students in a charter school, or they want their child at home with them. If they're not living in the Colorado Springs area, maybe they want them to be home and they don't want to have to send their child to live in the dorm. So actually, I think I'll mention again that all the districts are aware of CSDB, that it is an option, and discussions are happening during each student's IEP, just to make sure that we do provide CSDB as an option.

Warner: IEP is an individualized educational plan. There are any number of ways. I understand that the school benefits students statewide who may not attend the Colorado School for the Deaf and the Blind. Tell me about this resource of books in braille. If a particular book can't be found anywhere in the country, you have to make it and you print those. You press those here?

Spangler: Yes, we do. And then we ship them. We ship them all over to different districts throughout the state — all over Colorado. So we send them to students at their schools, in their home district.

Warner: So are there these printing presses on campus?

Spangler: Yes. It's called a braille embosser where you can print the actual braille.

Warner: And it's not just about embossing the braille. If there's a graph in a book, you have to have machines that replicate that in a tactile way.

Spangler: Yes. Using the thermoform. It's a machine, it prints the actual graphic.

Warner: We've got to talk about a teacher shortage, which is affecting all realms of education. You’re rolling your eyes a little bit as I ask this; I understand that this affects particularly education at the Colorado School for the Deaf and the Blind. Can you speak to that?

Spangler: Yes, you're right. There's a national shortage of teachers. We're really struggling just for general education for teachers. That means for special education teachers — specifically teachers for the deaf, teachers of the visually impaired — there’s even more of a shortage for us. It's a big concern right now.

Warner: Does someone who teaches at the Colorado School for the Deaf and the Blind have to have additional training? It's not as if a teacher who had not had experience with the student population could just walk in and run a class for you?

Spangler: Right. Our teachers — for example, an elementary teacher, should have two certifications. They should be a certified elementary teacher as well as be certified as a teacher for the deaf or visually impaired. Our high school math teachers must have a math license plus be certified as a teacher of the deaf or the visually impaired. So you must be double certified. Most of our teachers have a master's degree because it's required to have the double certification. So there is a lot of college for our staff.

Warner: Wow, that's a huge investment. And probably debt for those educators, I'm guessing. Are there ways, tools you have to increase the teacher core?

Spangler: We do provide some sign-on bonuses for new teachers. This year we provided some temporary housing for teachers who were relocating from out of state.

Warner: Was that a first?

Spangler: Yes. That is just for the first semester so they could save some money while they were searching for a place to live.

Warner: I think it's really important for the general public too, to understand that this school is offered tuition-free to any student who qualifies. Does that mean that there are people who try to become Colorado residents to go to this school?

Spangler: Yes. The only cost is the district itself for transportation. That's the only cost. Other than that, it's free. It's free for any student in Colorado who has an IEP, who is deaf, blind, or deaf-blind. Also, there are many students here whose families relocated here, in Colorado Springs specifically, just to go to this school and also we have a lot of military bases here locally in the Pikes Peak region. And some families will request assignment to come here to the Colorado Springs area if they have a deaf or a blind child. We do have some families who would request to be placed here for that reason.

Warner: That's remarkable. And I hadn't considered the military connection, but that makes a lot of sense. Given the missions — plural — of this school to serve deaf students, to serve blind students and deaf-blind students, there was some expression of concern over your appointment because you had less experience with blind education. Do you want to speak to that?

Spangler: So my formal education background is specifically for the deaf. However, since the year 2009, I've been working with both deaf and blind, both programs, here at CSDB. I also have worked as the curriculum teaching assessment coordinator, as well as a principal for K through second grade for deaf and blind, and recently the director of curriculum assessment. Through that experience, I've also attended trainings specifically for blind or low vision students as well. So formally with my degrees, no. But with my experience, I've been working with both deaf and blind students since the year 2009.

Warner: This year is indeed the sesquicentennial, your 150th anniversary. In April, 1874, seven students gathered in a house here in the Springs on their first day of school. And I just want to say, that predates the state itself by two years. Colorado was still a territory when this school was founded. Superintendent, I wonder if there is an alumnus you are particularly proud of? When you think about the legacy of this school.

Spangler: That's tough, just to pick one. We also have several alumni members who've come back to volunteer at the school. We recently just set up a new history museum, and we have a few alumni volunteers who come every Tuesday just to support the school with the new museum.

Warner: I wonder if we might speak to the importance of deaf and blind history so that students see themselves reflected in what they're learning.

Spangler: Yes, it's critical. It's important because we recently just celebrated 150 years of the school. We provided monthly history activities. We had videos, alumni interviews. We taught our students about the history of the school. And they’ve really enjoyed learning about the history.

Warner: You talked about alumni coming back to volunteer, coming back to teach, and I'm thinking about someone who I believe was a teacher of the year in the state of Colorado.

Spangler: Yes, she was a former student who returned here, and she became a teacher. She taught here at CSDB for many years. Her name was Bambi Venetucci.