Updated May 15, 2024, at 2:47 p.m.

Nearly 70 Colorado law enforcement officers have lost their state-mandated certifications since 2020 after being untruthful on the job.

While that number is far higher than state officials expected when a law passed several years ago that cracked down on dishonesty on the job in law enforcement, the real number of officers who get caught being deceitful is far higher.

Those officers’ stories are concealed from the public through resignations, retirements and transfers within agencies to protect the officers' ability to work in law enforcement — even when state law would seem to mandate the revocation of their certification.

Most everyone, including police chiefs and sheriffs, agrees that lying under oath during a criminal investigation should not only be a fireable offense but also decertifiable, which means an officer loses his license to ever be a peace officer in Colorado again.

But untruthfulness is obviously subjective: What about cheating a bit on a timecard? Or crashing a patrol car and not being upfront about what actually happened? What about not showing up for a 911 call even though an officer tells his boss he did?

A review of hundreds of pages of internal affairs investigative documents by reporters from Colorado Public Radio News and 9News found that officers were frequently fired or allowed to resign when caught not telling the truth but not then reported to state authorities as being untruthful.

Or, they were reported, but state officials didn’t decertify them. This allowed them to keep the certification to work as a law enforcement officer somewhere else.

That review identified 15 law enforcement officials who have a verified finding of untruthfulness from an internal affairs or criminal inquiry. All of these officers still have licenses to be peace officers elsewhere, if a department will hire them.

There may be more, but law enforcement agencies leveraged carve-outs in open records law that kept documents from being released to journalists.

Those officers include a southern Colorado sheriff’s deputy who told supervisors he stopped by a house after an armed trespass 911 call, but he instead signed off his shift. A man who damaged the front of his patrol car and then wasn’t honest about the self-checks on his car for weeks. And a man who was found to have been dishonest to supervisors about doing an initial screening on a suspect, before that suspect got into a police car with a gun in his pocket.

In all of these cases — and others — local or state officials say they didn’t rise to the level of pulling a license.

Standards of decertification

The state can only revoke a law enforcement officer’s certification if they were found to be dishonest while writing or testifying in any of three spaces: a police report, an internal affairs investigation or under oath. Deceits committed outside those areas could result in agency discipline, but not the loss of state credentials to work.

Other officers’ cases don’t meet the “clear and convincing” standard for untruthfulness to be decertified – even though most of these officers have been found to have been deceptive by internal reviews on the job.

Still, other cases don’t get investigated because law enforcement chiefs and sheriffs didn’t fill out proper paperwork at the statewide level to get it investigated or even disclosed.

The result: a state law that has proved at times to be flimsy and weighed down with exclusions that have allowed law enforcement officers to be untruthful on the job and keep their licenses.

Lawmakers said these faultlines violate the spirit of the law a reform-minded legislature passed five years ago to increase honesty among police.

They also said the law clearly relies too heavily on agencies policing their own and having the resources and stamina to file the correct paperwork with state officials to follow through with a decertification process.

It has become clear since the law’s implementation that with so many loopholes, agencies are often in internecine battles against one another — or the state — amid internal investigations about wrongdoing.

These weaknesses are no surprise to state Attorney General Phil Weiser, who has sought additional power and authority from the state legislature to conduct more aggressive peace officer investigations just this year. The bill to accomplish that, which was carried by state Reps. Leslie Herod and Jennifer Bacon, both of Denver, was killed in the state House of Representatives earlier this month.

The power of the training board

Six years into office and amid a second term, Weiser has tried to make Colorado a national model of transparency for law enforcement, which he believes will burnish their reputation, particularly since George Floyd’s murder in Minnesota in 2020.

Weiser acknowledged, though, that the success of holding officers accountable, for untruthfulness and everything else, relies on the power behind the regulatory Peace Officer Standards and Training Board, or POST. That state agency licenses law enforcement under the Colorado Department of Law.

Last year, an investigation by the nonprofit Colorado News Collaborative (COLab), The Sentinel in Aurora and Rocky Mountain Public Media revealed multiple loopholes, mistakes and regulatory blind spots that have kept officers with documented records of misconduct in good standing with POST. CPR News and 9News were among the coalition of newsrooms that used data made public by a 2020 reform law to take an unprecedented look at police discipline throughout the state.

In an interview for this story, Weiser pointed out that POST, and its one allocated statewide investigator, can only act on what they know. In fact, it’s baked into the law that POST is only allowed to investigate untruthfulness cases that are reported to them, and they aren’t allowed to go out and initiate anything.

It is also clear that untruthfulness is a bigger problem than lawmakers originally thought it was when they passed this bill in 2019.

At that time, officials estimated there would be four decertifications a year for dishonesty. That’s only a fraction of the almost 20 a year that has resulted since the law was passed.

Weiser, citing COLab’s reporting over the past year, said he sought greater authority and staff to go after law enforcement agencies not following the law. But given that lawmakers gutted the subpoena bill, they don’t have the power to require law enforcement agencies to hand over internal affairs or investigatory records either.

“Law enforcement agencies have to give us this information, but unfortunately we haven’t had as much authority if they’re not giving over the information,” Weiser said. “We want to make sure we have as much authority as possible to enforce the law.”

Weiser said at some point, he would like consequences for law enforcement agencies who fail to be transparent about untruthful officers.

But he will need to get that from the state legislature.

“If you did fail to tell us, we could pursue consequences,” the attorney general said. “Right now, we’re basically relying on them to do what the law says without any repercussions.”

In 2019, lawmakers passed the law that added untruthfulness into the “disqualifying incidents” for peace officers in Colorado. If an officer is found to be untruthful in a number of distinct settings on the job, they could be reported to POST for decertification.

It’s that last step that the attorney general and lawmakers say worries them — some agencies aren’t doing what they are supposed to do.

“I think relying on agencies that have more of a stake in keeping the information private is not good — we find there are some issues there,” Herod said. “While most agencies are following the guidelines, we have found that some are not.”

Costilla County no-show

On June 19, 2022, a 911 caller said his cousin needed law enforcement help confronting burglars in Chama, Colorado.

“Somebody is trying to break into his house,” the unnamed caller said on a 911 recording of the call. “He said he thought they may have weapons. He thought he saw a handgun.”

Costilla County Sheriff’s Office Deputy Mark Garcia told dispatch that he was on the way. Shortly afterward, he said the threat had passed, according to internal affairs documents and the 911 tape recording.

“I passed over there, like, literally about five to 10 minutes ago,” Garcia said. “I didn't see anybody over there. So I called him, like, four times. He doesn't want to answer. I don't want to really wait around for him to call back.”

Garcia then signed off for the day, according to the 911 audio.

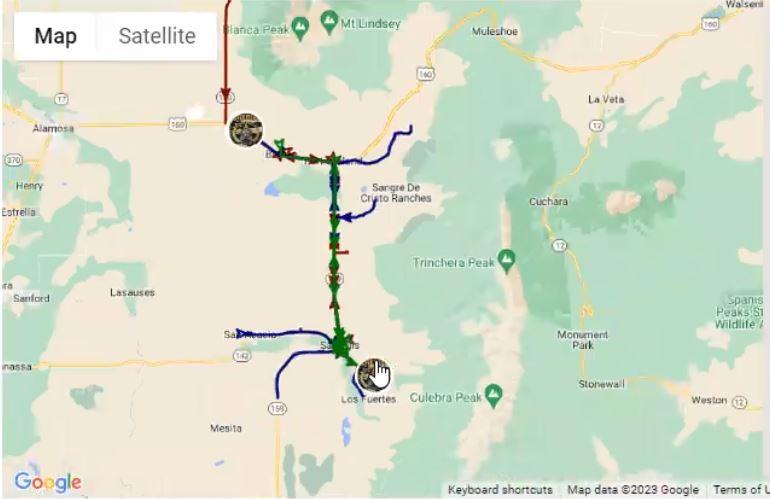

But Costilla County supervisors eventually discovered through GPS coordinates from Garcia’s body-worn camera that he was never in the vicinity of the 911 call.

Back-up deputies decided to go out — and were surprised when Garcia closed out the call early. About an hour after that first 911 call, the homeowner, who hadn’t heard from any law enforcement, nearly shot one of the deputies who arrived as backup.

“As I started into the residence I heard rustling around in the first bedroom,” Cpl. Keith Shultz wrote. “I started to make entry into the room and was [met] by a rifle in my face.”

Shultz wrote that he was able to talk to the homeowner and avoid being hurt.

“The stand-off ended peacefully, but all could have been avoided had Garcia gone out there what he was called to go out there,” Shultz wrote.

9NEWS and CPR News have pieced together the events of the call through records requests, partial dispatch audio and documents generated through the internal affairs investigation. Body camera footage from the call was deleted after 180 days because there was not a criminal charge, according to an emailed statement from Costilla Undersheriff Cruz Soto.

Garcia did return requests for comment and left a reporter a voicemail.

“I’m more than willing to give my side of the story for your article and shed some light on a lot of the things that happened over there,” Garcia said in the voicemail.

He did not respond to multiple follow-up attempts to connect.

Garcia told internal investigators that he had personal issues at the time and could not be late to pick up his kids, according to a report written by Costilla County Sheriff Danny Sanchez.

The Costilla County Sheriff’s Office reported Garcia to POST, according to a form obtained by 9NEWS and CPR News.

“Based on our findings we are hereby notifying Colorado POST that we feel Mark Garcia was deceitful while employed as a Deputy Sheriff for the Costilla County Sheriff’s Office,” Sheriff Danny Sanchez wrote.

Erik Bourgerie, POST director, said in a written statement that Garcia’s case did not meet the legal “clear and convincing standard” of untruthfulness in either an administrative or disciplinary process.

Anne Kelly, the Costilla County district attorney, disagreed with state officials and sided with the law enforcement agency. She sent a so-called Brady letter to defense attorneys warning them that Garcia was not credible and his actions were “dishonest.”

Garcia was ultimately fired from the Costilla County Sheriff’s Office in July 2022.

But Garcia did not have to wait long before re-joining law enforcement nearby — as a police officer in Springer. Springer is a small town in northern New Mexico roughly 48 miles from the Colorado border. The Springer Police Department announced Garcia was sworn in on May 10, 2023, alongside a short biography.

“Officer Garcia comes to us from Colorado with 10 years of Law Enforcement experience as a certified street cop,” an unnamed police department official wrote on their department’s Facebook page.

A Springer town official did not return multiple requests for comment. New Mexico does allow law enforcement officers to gain certification there if they have similar experience in other states. They also decertify officers for dishonesty.

The definition of untruthfulness in the eyes of the beholder

Five years ago, the idea to decertify officers because they lie on the job came from the law enforcement community itself.

Democratic state Sen. Dylan Roberts, who was in the state House in 2019, said that law enforcement approached him with the idea.

“They said, ‘We know there are officers making untruthful statements, but there is no mechanism in state law to do anything about it,’” Roberts said, in an earlier interview. “It was about protecting the integrity of the profession. It’s the few bad apples that put a stain on the rest of the officers in the state.”

But in the first years of the law’s implementation, it is clear there is broad subjectivity on what is an act of deceit that merits a license being yanked versus something that merits termination — or simply some discipline.

It depends on the judgment of varying public servants in different layers of local government.

Rachel Moran, a law professor at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota who has studied policing since 2015, said 9NEWS and CPR News’ findings identified “significant gaps” in the law such as a standard for decertification that may be too narrow.

“It shows to me a flaw in the laws, the way we allow people to be officers despite deception,” she said.

In other words, untruthfulness is in the eye of the beholder.

And that subjectivity threads through, and sometimes feeds interagency division, miscommunication, infighting and varying conclusions among state and local officials.

Limitations of POST investigations

Take the case of Spencer Davis.

On Jan. 3, 2022, Davis, a Colorado State Patrol trooper, told his supervisors at the end of a shift that he noticed some damage to the front of his car and he didn’t know what had happened.

He said he inspected his work vehicle before starting his shift – but he admitted later that he didn’t actually perform a complete and proper inspection, according to the records.

State patrol supervisors also discovered that Davis had worked at least six shifts between when the damage occurred on his vehicle and the day he reported it to supervisors. This sparked a six-month internal affairs investigation that ultimately concluded that Davis was dishonest about conducting required inspections of vehicles and about what happened.

“Clearly, Trooper Davis neglected to perform his duties,” wrote Major David Rollins, according to redacted internal affairs investigation documents obtained by COLab. “Additionally, Trooper Davis misled his supervision when he claimed he performed a vehicle inspection and did not see damage prior to his shift on January 3, 2022.”

The Colorado State Patrol fired Davis.

However, Davis was able to retain his certification to work in law enforcement when POST was ultimately unable to get a copy of the internal affairs investigation CSP relied upon to fire him.

Lacking the authority — and frankly the resources — to conduct independent investigations, POST counts on agencies to provide them with the evidence they would need to determine whether a certified law enforcement officer was untruthful.

In Davis’s case, he hired an attorney, who was able to negotiate with CSP, releasing the agency from the possibility of a wrongful termination suit in exchange for them altering Davis’s separation from a termination to a resignation.

Then POST said the agency refused to release records.

Davis was then able to get a job with the Summit County Sheriff’s Office.

And there his record of untruthfulness followed him in the form of a Brady letter, the district attorney’s warning to defense lawyers that a law enforcement officer has a credibility issue. But Davis’ lawyer managed to get even that watered down to a notice that Davis had a prior finding of failing to follow CSP rules.

Despite his settlement with CSP, POST has refused to change the public record of Davis’ firing to resignation ”because of a negotiated settlement that does not reflect factual circumstances,” wrote POST Director Erik Bourgerie.

Without CSP’s internal investigation, POST cannot take any action toward potential decertification.

Davis remains a certified law enforcement officer, still working in Summit County.

The entire saga, which all started with a broken bumper according to records, underscores the interagency division, miscommunication, infighting and varying conclusions state and local officials can have when determining whether someone deserves a second chance or not.

Herod said the state’s authority created under the untruthfulness law was actually intended to solve for many of these disagreements.

“All officers were supposed to be decertified for a certain set of reasons and be in the database so they, one, could never work in the state of Colorado again as a law enforcement officer, but two so they couldn't shop around their resume and ignore the fact that they had left under investigation or because of wrongdoing,” Herod said.

Deceit in the right setting

In other cases, officers may have been found to be untruthful — but they weren’t untruthful in the correct way that allows for decertification under state law.

Like former Greeley Police Officer Zach Lopez, who is one of the 15 law enforcement officials who kept certification after a sustained untruthfulness finding.

Lopez was officially fired for incompetence, but the police chief thought it should have been for untruthfulness according to Greeley police records. Two tiers of police review were overruled.

Body camera footage shows Lopez approaching a man smoking a cigarette outside an arcade in September 2022. Officers arrested the man for a possible warrant. The man was handcuffed and sat down in the back of Lopez’s police car; cigarette still lit.

When Lopez told the man that he had verified that the warrant was active, the suspect made a confession.

“I have a firearm,” the suspect said, according to body camera footage.

“Can I pat you down real quick?” Lopez asked as he motioned the man to stand up.

Lopez handed another officer the suspect’s tan handgun. It was loaded.

Lopez told investigators that he did not search the arrestee before putting him in the car because he had a concealed carry card. The internal affairs investigator wrote there was no record of the suspect having that license, nor of Lopez having looked for it.

“Lopez’s [body worn camera] was watched and showed no evidence that Lopez had searched the prisoner’s wallet,” to look for a concealed carry card, Kyle Peltz, a sergeant within the Greeley Police Department’s professional standards unit, wrote. “The totality of this presented evidence that Officer Lopez was being untruthful regarding the details of this event.”

Lopez, in an interview with 9NEWS, chalked up his transgression to a mistake and not purposeful deception. He said he misremembered the concealed carry card and put it into his report without pausing to check his body camera footage.

“I slept better at night knowing that this was a human mistake,” Lopez said. “And, you know, it doesn't make it any better, but it wasn't like, you know, it wasn't intentional.”

Lopez said he did not feel an immediate need to search the man because the suspect was calm and there were other officers present.

“So had I gotten that opportunity to search him and he hadn't told me that he had a weapon, he absolutely would have been searched,” Lopez said.

Daniel Stageman, director of research at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said he thought Lopez displayed more “rank incompetence” than untruthfulness but that POST should have pursued decertification.

“You use the mechanisms that you have available to you to try to achieve the kind of outcome that is appropriate,” Stageman said. “And it's definitely appropriate that this guy should not be a cop anymore. He's gonna get somebody killed.”

Untruthfulness — overturned

Lopez’s supervisor and the police chief found that Lopez was untruthful. The city manager agreed on the firing but overturned the untruthfulness portion.

“I find that your statements to Sgt. Fisher and in the supplemental report, while demonstrably inaccurate with regard to the existence of a concealed carry permit, were not knowingly untruthful,” City Manager Raymond C. Lee III wrote.

This means Lopez could not be decertified under Colorado’s statutes because the city manager wrote he should be fired for incompetence, not untruthfulness.

Jaqueline Villegas, a spokesperson for the City of Greeley, wrote in an email that Lee maintained the firing of Lopez using the sections of the city handbook that mandate competence and following all federal, state and city ordinances.

“We’d like to reiterate that City Manager Lee did not overturn any decisions,” Villegas wrote. “Rather, he upheld the termination through the lens of ‘clear and convincing evidence...’ ”

The case was not brought to POST.

Lopez said Lee overturned the untruthfulness portion of his termination because he demonstrated that it was not a purposeful lie, but instead a lack of attention to detail.

The lack of search leads to a change — and calls for more

Greeley Police Chief Adam Turk wrote that Lopez’s case showed the need for internal policy changes. Officers are now required to pat down suspects “prior to being placed in a vehicle.” Previously, the search had to happen before they were “transported.”

Lopez’s case exhibits how hamstrung POST is, said Moran, the law professor at St. Thomas.

She called for POST to have more power to initiate investigations without a referral from a local law enforcement agency and more authority outside of the narrow instances outlined in the statutes.

“They should have the authority to decertify officers for any lies, any intentional lies related to public safety instead of confining them to the narrow contexts of the law,” she said. “That would eliminate some of the significant gaps.”

Lopez said he is working with his attorneys to get his credibility report removed from the POST website. He is unsure whether he wants to go back into policing.

But, if he finds a job, he can if he wants to.

Susan Greene, Andrew Fraieli, Brittany Freeman and Alison Berg contributed to this report.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to clarify that a bill to increase POST power failed in the legislature this year.