A new report shows economic and racial segregation in Colorado schools has increased over the past three decades and in some cases at a faster rate than the national average, according to a new report from Stanford and the University of Southern California education researchers.

The report coincides with the 70th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision that overturned the policy of separate but equal and the constitutionality of state-sponsored segregation in public schools.

“School segregation levels are not at pre-Brown levels, but they are high and have been rising steadily since the late 1980s,” said Sean Reardon, the Professor of Poverty and Inequality in Education at Stanford Graduate School of Education and faculty director of the Educational Opportunity Project.

The study also found the increase appears to be driven in part by policies favoring school choice over integration, though one local researcher urges caution when applying that to every district.

Users of a new interactive website Segregation Explorer can look up segregation patterns in all of the country’s school districts. (The number 1 indicates a fully segregated school and the number 0 indicates a completely integrated school.)

What are Colorado’s school segregation levels?

Colorado’s current level of Black-white school segregation is in line with the average for all states. The state’s white-Hispanic segregation level is higher than the national average — Colorado ranked 20th in the nation.

The biggest segregation gaps in the Denver-Aurora-Centennial area are between low-income students and their wealthier peers. Economic segregation increased 38 percent over three decades compared to 12 percent on average for the 100 largest metro areas in the nation, said researchers.

This implies that lower-income students are clustered in schools with other low-income students, according to Ann Owens, a professor of sociology and public policy at USC.

In the Denver-Aurora-Centennial area, segregation between Black and white students increased by about 18 percent from 1991 to 2019. That’s in line with the average trend among the 100 largest metro areas.

Segregation between white and Hispanic students in the metro area increased by about 26 percent, which makes the increase in absolute terms on par with the average for other large metros. Among the 100 largest metro areas, Denver is in the top 20 for white-Hispanic segregation in recent years.

A separate study last year found pervasive segregation in Denver Public Schools and recommended further studies into the causes and mechanisms behind segregation.

Why is school segregation increasing?

Researchers said there is a tendency to attribute segregation in schools to segregation in neighborhoods. But they said in most large districts, school segregation has increased while residential segregation and racial economic inequality have declined.

They said one factor accounting for the rise in segregation was the release from court-ordered desegregation oversight.

In 1973, the Supreme Court mandated the integration of Denver’s schools. The Keyes v. Denver School District No. 1 set a precedent that would go on to influence desegregation cases throughout the country. That two-decade experiment ended with a court ruling in 1995.

Researchers also assert that the choice to expand charter schools over integrating schools has played a major role in the increase in segregation.

“Our findings indicate that policy choices – not demographic changes – are driving the increase,” said Reardon.

But drawing a clean line from the rise of charter schools to increased segregation is problematic for some

Parker Baxter, director of the University of Colorado Denver’s Center for Education Policy Analysis, cautions that the finding on school choice doesn’t take into account local communities, identities and differences.

For example, what exactly was the influence on segregation when DPS added 20,000 new students between 2008-19 and the percentage of white students increased by 5 points?

While Baxter, a former director of charter schools at DPS, said he knows there may be charter schools in some Colorado communities that operate as opportunities for “exclusion and separation,” DPS tried to avoid increasing segregation.

“That's why we took steps to mitigate that risk with things like the common enrollment system.”

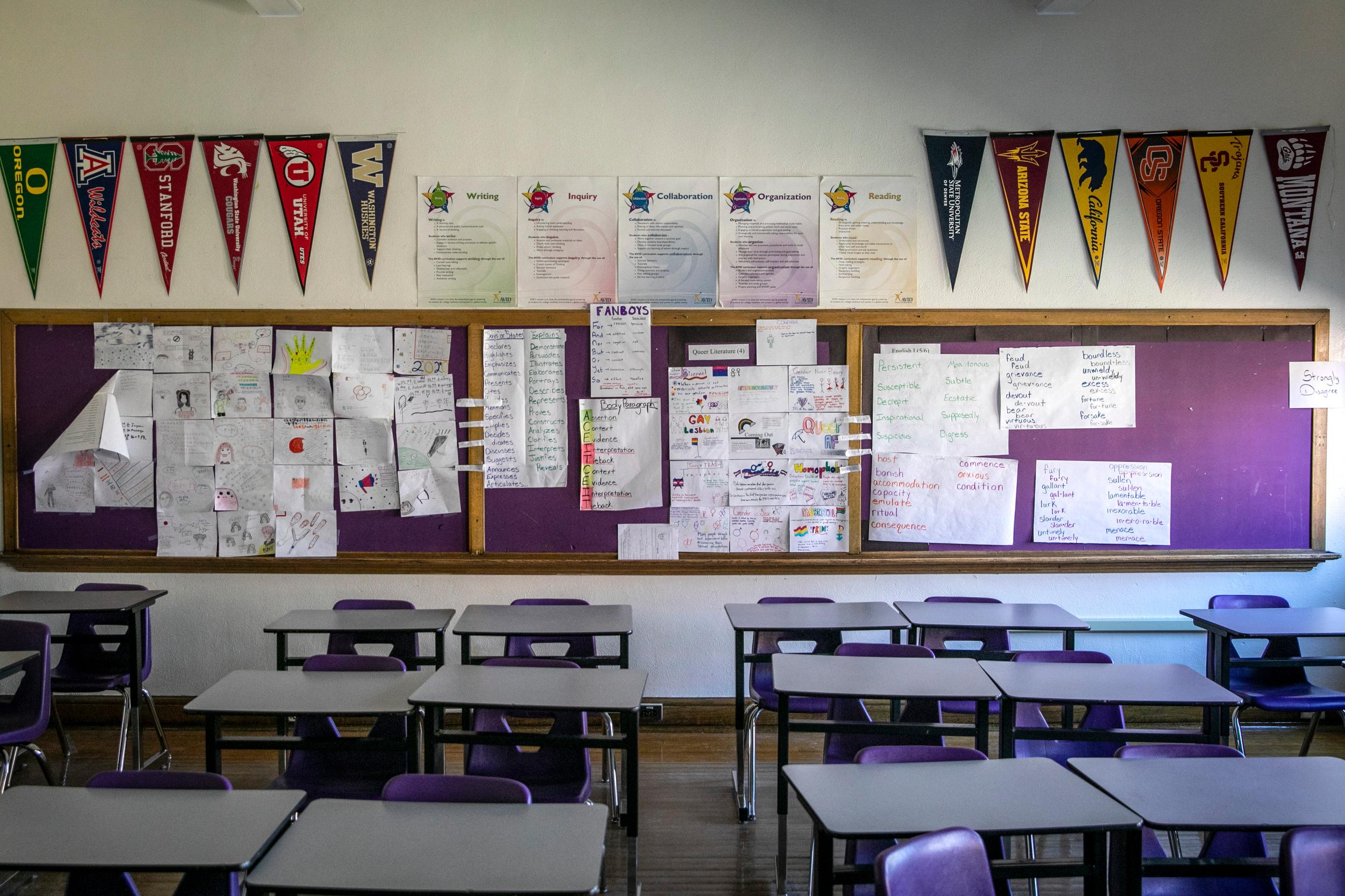

Common enrollment ensures that students have equal access to all schools. The data show that in a city like Detroit, which has a large charter sector, segregation increased much more significantly than in Denver, which created more than 50 charter schools between 2005 and 2019. About one in five children in DPS attend a charter school.

Baxter said the district had the intent of creating diverse charter schools. Some purposefully set up in heavily Latino neighborhoods to have the same demographics as traditional neighborhood schools.

He said the studies’ findings also don’t mean that charter schools have contributed to achievement gaps between racial and ethnic groups.

“Segregation in and of itself is not a proxy for gaps in academic performance.”

Baxter led a research study showing DPS’s decade-long embrace of school choice led to large academic improvements.

In addition, some Black scholars and activists see school choice – the opportunity to congregate in spaces where they are the majority - as a form of liberation for their communities. For example, DPS will have a charter school next year with a focus on Black students and culture.

“We probably are not going to be able to mandate our way to integration and we definitely shouldn't fall into the trap of thinking that Black and Brown students need white students in their classrooms in order to achieve,” said Baxter.

Other efforts at driving socioeconomic integration in city schools, such as prioritizing low-income enrollment at some affluent schools, have been mixed.

All researchers agree policy choices matter. What works is still up for debate.

It’s unlikely that desegregation, in the form of busing children, would ever return.

Mike Atkins, DPS’s director of Black Student Success, attended district schools during the era of busing. He spoke at a symposium, Integration and Equity in Denver Public Schools 50 years after Keyes, in February.

“What happens when you are forced to go to a space where you're not seen, not heard, and not loved? I grew to hate school,” he said.

But integration, systems that recognize every student’s power and humanity, is something that is achievable.

“What was lacking (during busing) was the intercultural development of our educators to truly understand that the ask shouldn't be for our babies to assimilate to school. It should be ‘How are we shifting our culture to the students that are in front of us?’”