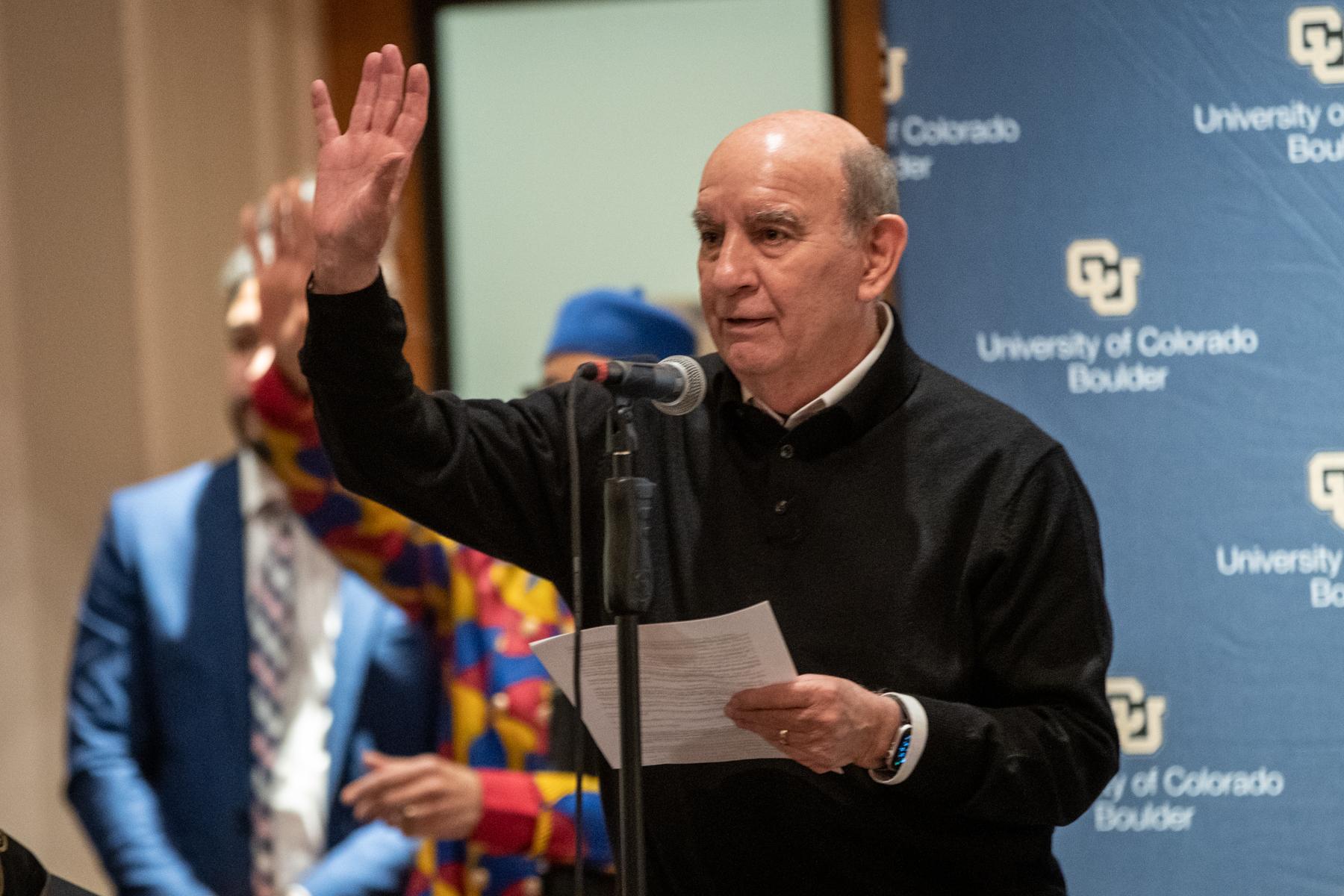

In 1974, Philip DiStefano walked through the doors of the University of Colorado Boulder’s School of Education as an assistant professor. What followed was a 50-year tenure at Colorado’s flagship university in multiple roles, including the chancellorship, the position DiStefano is preparing to vacate this summer.

Over the last 15 years of DiStefano’s tenure as chancellor, he has navigated the university through numerous challenges, including higher education funding and the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of those challenges he faced will be inherited by his incoming successor, Justin Schwartz.

“Higher education, as you know, is under fire nationally, and the value of higher education is being questioned,” he told CPR News.

Colorado Matters sat down with DiStefano at CU’s Lucille Buchanan Building, which is where his office was located when he first joined CU 50 years ago. There, he reflected on how higher education has changed during his long career and challenges his successor will have to navigate.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Paolo Zialcita: We're sitting in an old building, I've been told it's the old education building. There's a chalkboard behind you. It does look a little dated. You started your lengthy CU career in this building. What comes to mind as you sit in this building 50 years later?

Philip DiStefano: Well, 50 years later, and when we're finished here, I'm going to go downstairs. My office was [Room] 103. I think it's still there. I'm sure it's still there.

But when I come into the School of Education, I really do think back 50 years ago, and 1974, there was quite a bit going on on the campus from the standpoint of protests, mainly protests against the war in Vietnam. And one thing that I remember very vividly is that many of the academic units across the campus, including the School of Education, moved to a pass-fail for a couple of years rather than giving out grades. And it was the department's choice at that time to do that.

But I had great students back then, and many of them went on to teach both in high school and junior high school, middle school. And I still hear from them and so that's wonderful. And many of them have retired from teaching. But for me, it was a very rewarding experience — the time I spent here in the School of Education.

Zialcita: Did you imagine the man who walked into this building 50 years ago becoming the chancellor for the entire university?

DiStefano: Not at all. Not at all. And as a first generation college graduate, I was, number one, so thrilled to be able to have a professor's job here at the University of Colorado. And 12 years after I arrived on campus, I became the dean of the School of Education.

Again, it wasn't anything that I planned. There were some factors going on at the state level, and the dean resigned at the time and I was asked to step in and was dean for 10 years and then moved into other campus administration and finishing as the longest serving chancellor of the university.

Zialcita: What drove that ambition? You said you didn't plan to become dean, but then you continued to move up.

DiStefano: Yes, well, the motivation there was just the opportunities that I had. And after being dean for 10 years, I was ready to go back to the classroom and do my research and teaching.

And I had this opportunity to be the associate vice chancellor, the first associate vice chancellor for undergraduate education, and we expanded the number of undergraduate programs during that time. It was only for about two years, and then the provost left and I moved into that position and did that till 2009.

I just kept getting offers to move up and I care about the university and cared about the university back then and thought that those would be good moves for me from a professional standpoint. And they've been incredible.

Zialcita: As you sit here 50 years later, how was the university and higher education as a whole changed during your time?

DiStefano: Well, from the standpoint of the university, the University of Colorado, we've seen a significant increase, for example, in research funding. We're one of the top research universities in the country. And in the 15 years that I served as Chancellor, we doubled our research funding to just about $700 million this year. We've also doubled the amount of money raised each year through private fundraising. So I'm very pleased that, during the 15 years as chancellor, there have been just some incredible things that have happened, mainly because of the quality of the faculty that we hired and the quality of students and staff.

On the other hand, higher education, as you know, is under fire nationally, and the value of higher education is being questioned. And when you look at the data, the data certainly support higher education from an economic standpoint of college graduates making more money in their lifetime than non-college graduates. The unemployment rate for college graduates is much lower than for non-college graduates. At the same time, my main concern is making sure that our students succeed while they're here. And that doesn't just mean getting a degree. Getting a degree certainly is important, but I also want them to graduate as good citizens and give back to their communities in a variety of ways.

So I've spent quite a bit of my 15 years talking about the importance of preserving our democracy. And especially in the last five to seven years, spending quite a bit of time talking about that. And it's the next generation, so it's these students who are graduating that I'm looking forward to seeing what they do because I believe, from a leadership standpoint, they're going to ensure that the democracy, our democracy stays strong.

Zialcita: There are two things I wanted to talk about in your answer there. You spoke about the quality of students being better now. Tell me about the difference in students now and then. Maybe they are completely different, but perhaps are there similarities that you've noticed? Are they just as active politically as the Vietnam war protesters you talked about in the '70s?

DiStefano: I believe that the students are as active today as they were 50 years ago. However, what's changed is the way that they've shown their activism. For example, we didn't have any encampments as many universities across the country, but that doesn't mean that students weren't voicing their opinions about the war that's going on between Israel and Hamas.

And they voiced their opinions in a very civil way. We've had protests on the campus, but as I watch the protests and I talk to students, they've done it very respectfully. And that wasn't the case 50 years ago. And actually, it's not the case in many universities today.

So I'm really pleased about that, that they're voicing their opinion, they're voicing their free speech, but they're doing it in a way that's respectful of the other side. And just last week, we had a protest of about 50 students that was at the student union and then moved to the library. And again, very peaceful. They certainly discussed their points of view, but they did in a very respectful, civil way.

Zialcita: And you spoke about the challenges that higher education is going to be facing. You've led CU through many of those challenges, namely the COVID-19 pandemic. Higher education, like you said, isn't out of the woods yet. It's under fire. Some students are perhaps signaling that it isn't within their priorities. What challenges do you anticipate will hit higher education in the coming years?

DiStefano: Affordability is an issue and there's no doubt about it. And one of the things that we've done here at the Boulder campus of the University of Colorado is we have, for the last, I would say 10 years now, guaranteed tuition so that our students come in as first-year students and they don't pay any additional tuition or fees for four years. And what we've seen is an increase in the graduation rate in four years because students who stay a fifth year pay what the new students are coming in. So the only students that see an increase in tuition are the first-year classes that come in. And that way parents can plan and students can plan.

The other is making sure that for our very low income students that we provide, we have the Colorado Promise. And the Colorado Promise is if a family is making $65,000 or less per year, that their children can come here without paying, with free tuition and fees. And if it's below $60,000, we actually add another $5,000 besides tuition and fees for living expenses. So what we're trying to do is make it affordable for students, and I've been very pleased that our faculty and our deans, our administration, the leadership here, that they've been very vigilant and deliberate about affordability, but affordability is an issue.

Zialcita: Do you perhaps have any regrets over anything you were unable to address during your chancellor tenure? I'm thinking about challenges your successor will navigate, increasingly frustrated workforce shortcomings with diverse student populations. The perpetual question of tuition costs, like you're talking about.

DiStefano: Right. Well, my advice to the new chancellor, that advice falls into a number of categories. The first is the priority should be on student success. And I believe we have a moral obligation that when we admit a student to the university, we should do everything we can to make sure that student's successful. Because students, about half of our in-state students, take out loans so they have debt when they graduate. And what's worse than having debt when one graduates is having debt and not graduating. And so I want to make sure that the focus really is on student success and we see our retention rate increasing, which we have seen over the last four or five years, and also our graduation rates increasing. So that focus on student success, I believe, is very important.

The other bit of advice I would give the new chancellor, besides student success, I think the other bit of advice I would give to the new chancellor is to continue to build a strong relationship between the city, the county, and the university. The town-college relationship is so important. And then thirdly, in today's world, we can't ignore intercollegiate athletics. Right now, intercollegiate athletics is going through major, major changes and whether we're going to see intercollegiate athletics as it is today in the future, I'm not sure because of everything that's going on. I spend about 30 percent of my time on intercollegiate athletics, which when I first became chancellor and previously to my chancellorship, I doubt if the chancellor spent more than 10 or 15 percent. So that does take up quite a bit of time.

The other bit of advice is on shared governance. Higher education is very different from other institutions, organizations in that we work together in shared governance, the faculty, staff and students. So the faculty have quite a bit of say, of course, the staff as well, and our students. We have a very strong undergraduate and graduate student government. And by collaborating and working together, which I believe we have, we've seen, as I mentioned, the protests that we've had have all been very civil. I believe that's because of shared governance. And then the final thing I would say in higher education, which is important, is to practice what I call humble leadership from the standpoint of being the chancellor. It's not just an authoritarian top-down model that we need. We really need to have that type of collaboration among the faculty, staff, and students. And I believe that that's why I've been successful and that's why I've been the longest-serving chancellor is practicing that humble leadership with the faculty, the staff, and the students.

Zialcita: How does the future chancellor balance the need to cater to intercollegiate athletics, which you say is very important, but also cater to the needs of the faculty? I speak monthly to faculty members and staff members who say they're overworked, they're underpaid. Meanwhile, Deion Sanders is making $30 million, and the university is giving money to the athletics department to fund that. What are your thoughts on that?

Well, number one is, I see intercollegiate athletics as being kind of the front porch to many things that go on at the university. And the job of the chancellor, in my mind, and the way I've practiced it, is much more external than internal. And so I spend quite a bit of my time on the road meeting with alumni donors, friends of the university, parents of the university. And it's interesting that I probably hear more about athletics from our alumni and our donors than I hear about the history department or engineering. So when you look at intercollegiate athletics, it's been part of the culture in higher education. And that's not to say that faculty salaries, staff salaries are not important. I spend quite a bit of time at the state legislature working on those issues as well and working with our congressional delegation in Washington.

So the new chancellor coming in will spend his time with much, much more external than when he was a provost. When I was a provost, almost a 100 percent of my time was internal on the campus working with deans, department chairs, research, and student affairs. But when I moved to the chancellor's position, it became a much more external position.

Zialcita: Speaking of your successor, Justin Schwartz has been named the next CU chancellor. He comes from an engineering and STEM background, a stark contrast to your education background. Does that signal the direction of Colorado's flagship university?

DiStefano: I don't think so. The chancellor before me, Bud Peterson, also had the engineering background. And I think when you look at chancellors and presidents across the country, especially in the Association of American Universities, the AAU, I'm actually an anomaly having a faculty position in our school of education and having a degree in humanities education. Most of the presidents and chancellors in the AAU really come from engineering, law, and certain sciences. So I am sort of the odd person out on that one.

Zialcita: Are you worried about the future of liberal arts education in the country? You're an anomaly, like you said, but liberal arts [jobs are] probably less paid than STEM jobs, probably less desired than STEM jobs. How do you appeal to students who want to pursue those jobs but are being a little more realistic?

Right. Well, one of the things that we've done here that I'm extremely proud of is that our Leeds School of Business has worked with the College of Arts and Sciences, especially in areas in the humanities, like philosophy and history and english. And the Leeds School of Business has put together a minor in business for arts and sciences students. Because as you said, we were seeing a decline in the number of students in especially the humanities in some of the areas of social science. Now we're seeing that plateau and actually even going up because students are getting, say, a history or philosophy degree with a business minor, and they're getting jobs. And actually, employers are looking for those individuals who can think critically, write critically, speak critically, but also have some of that business background.

So the other thing that we're doing that I'm very proud of is we offer an entrepreneurship certificate for non-business majors. So students in our College of Music, for example, will take on the entrepreneurship certificate because they're looking to go out on their own and not all of them are going to be singing at the Met or being on Broadway, but they may want to do some other things that are much more innovative and entrepreneurial. So this certificate has really helped them. Our students who are getting a journalism degree in the College of Communication, Media, and Information, CMCI, are also taking on the entrepreneurship certificate. So what we have to do, and again, it comes back to student success, we have to provide students who want to major in areas like music or journalism or arts and humanities, other options like the minor in business or the entrepreneurship certificate.

Zialcita: So really just make these students more well-rounded.

DiStefano: Exactly, exactly.

Zialcita: In your 15 years, I'm sure you've had many discussions with the state legislature about the funding of higher education. In the past four years, we've seen lots of battles over it. We've seen debates about TABOR, we've seen debates about how much higher education actually needs. How do you feel about the progress made? Have you felt that there has been progress made in that field?

DiStefano: I feel there has been. About four and a half percent of my budget comes from the state's total budget, so it's a little bit over $2 billion. And about four and a half percent of that, about roughly a hundred million come from the state. So realistically, the state doesn't have the funding that other states have because … our population is much smaller than other states, but I still believe that we're a state-funded school, and we should work with the legislature every year to get more funding. At the same time, you have to be realistic about it and look for alternative sources of revenue. For example, fundraising, private fundraising, so in the last probably five to eight years, raised more money than what we were getting from the state. So that has helped, and that money can be used. It's directed to scholarships and so on.

We also have to be entrepreneurial from the standpoint of startup companies. So right now, the University of Colorado Boulder is fifth in the country in startups. And when our faculty do startups, a percentage of the money comes back to the university. So we have to look at ways of increasing and diversifying our revenue streams. Certainly, we'll continue to work with the state every year, and the legislature, I believe, has been very positive about higher education in this state in the last four or five years. Again, there's not the dollar amount that other states have, but we continue to work with the state. But to do the things that we need to do, we have to diversify our revenue and look at different [ways] of bringing in money to pay for faculty salaries, staff salaries, the technology we need and so on.

Zialcita: I know you're not going very far. I know you're not leaving CU quite yet. You're returning to the School of Education, but what do you want your final rallying call to the CU community, to Boulder to be as you leave office for the final time?

DiStefano: Well, I think as I leave the Chancellor's office, obviously, I wanted to make sure that the university is better off today than it was 15 years ago. And I believe all the data show that we are with our research funding with 68,000 applications for this fall for 7,000 students, what we've done in fundraising, all of that can be improved.

But I'm leaving feeling positive about the improvements that occurred during my tenure here. But as you said, I'm not leaving and I'm looking forward to working with undergraduate students in our leadership program. We have a minor in leadership on the campus for about 500 students, and my goal is to double or triple that in the next couple of years. I came here as a faculty member doing research and teaching and service, and I want to go back to that before I fully retire because that's why I came to the university.

Zialcita: Chancellor, thank you.

DiStefano: You’re welcome, thank you.