The smoke had barely cleared from the first of two fatal 1974 explosions in Boulder when police settled on a theory of the case.

“Investigation by the Boulder Police Department and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms indicates that the explosive device and all three victims were in the passenger area of that vehicle and that one or more of the victims was in the process of arming the device at the time of the explosion,” reads an FBI summary a month after the May 27 blast that killed three people in the car.

That agency, along with Boulder Police and the ATF, reached a nearly identical conclusion about a second blast that happened just two days after the first and also killed three.

They were just two among several Colorado bombings that occurred in the early 1970s and appeared tied to the Chicano movement in the state – but they were the most violent. In hundreds of pages of reports compiled after the deaths and reviewed by CPR News, investigators assembled substantial evidence to attribute some of those other cases to some of those killed among Los Seis.

Those theories, however, were never tested in court. No one was charged in the fatal blasts, or in the other explosions on and off the University of Colorado campus in Boulder.

Now, in the midst of the 50th anniversary of the fatal bombings, the university and its home in Boulder are embracing the complex history of Los Seis. A memorial to them has received a place on campus, in front of a building the ATF speculated that the students wanted to destroy with the first bomb before it accidentally detonated. A scholarship has been created to remember the students. The city of Boulder dedicated another memorial to the six on Tuesday evening.

The passage of 50 years has done little to soften the suspicions of Chicano activists and supporters about the conclusions of local and federal investigations into the explosions. They simply don’t believe investigators adequately considered alternatives to the theory that the activists died in accidents while constructing bombs.

That distrust is based in the protests of the 1960s and ‘70s, when the FBI acknowledged a long and documented history of infiltrating activist groups, but even today, the distrust persists.

The explosions followed weeks of protests by Chicano students who had reached a breaking point over several university attempts to assert control or influence over the Mexican-American student association and the Chicano studies program, including concerns that student financial aid could be frozen or cut. At their core, the complaints were rooted in the notion that students were being denied the education they needed to be upwardly mobile in American society.

The six who died, among them a young attorney, a former homecoming queen, an aspiring doctor and the former president of the Mexican-American student association, were active in the Chicano movement. After their deaths, they were considered by supporters as martyrs of the movement.

Over time, the possibility that the six died in accidents while preparing bombs was simply omitted from news stories, and even from university publications.

The university has copies of the FBI and ATF reports documenting the investigations into the bombings, and the conclusions reached by authorities. They are kept in a box in the basement of the university library, about 540 steps from the memorial, but it is not clear whether any contemporary university officials have read them.

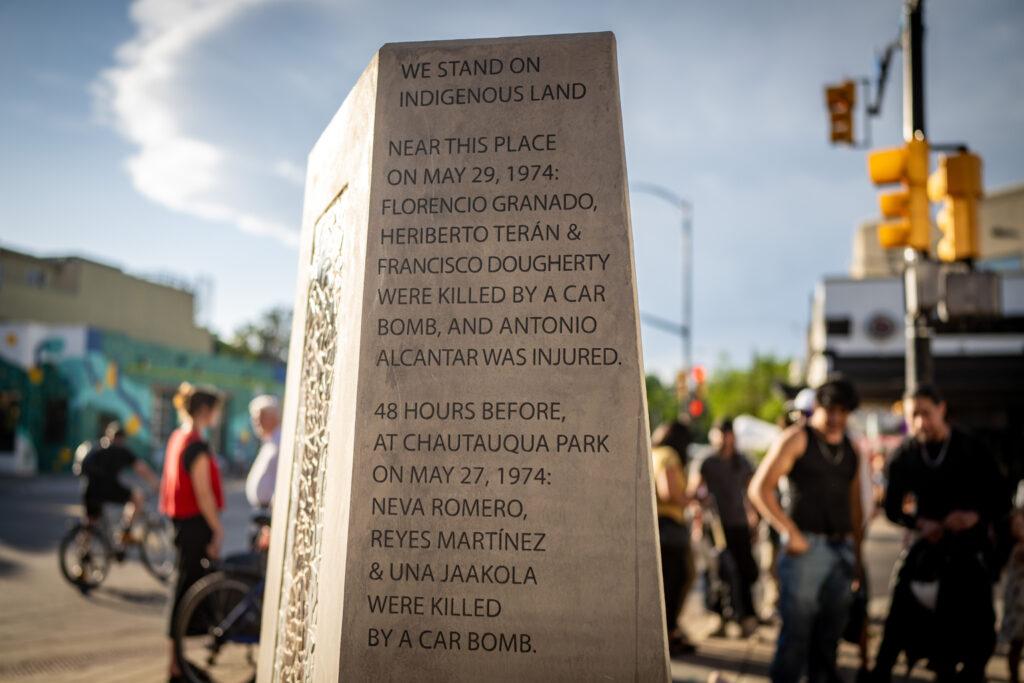

This month, the Boulder City Council passed a proclamation recognizing the anniversary and positing that the deaths remain a mystery 50 years later. Tuesday evening, the city dedicated a memorial sculpture to the students in a prominent spot downtown, along Pearl Street.

“For almost a half-century the case has remained unsolved and shrouded in mystery,” said Boulder Mayor Pro-Tem Nicole Speer, reading from the proclamation at the city council meeting. “And for most of that time, Los Seis de Boulder and their deaths have gone unrecognized by City of Boulder residents, businesses and institutions.”

Students active in the University of Colorado’s Chicano movement never believed the official explanations for how their friends died. Then and now, the federal government evoked a mixture of distrust and enmity from activists wary of the FBI’s use of informants and surveillance to track activist groups in the 1960s and ’70s.

| How and why did we report this story? As the 50th Anniversary of the explosions that killed Los Seis de Boulder approached, CPR News set out to understand and tell the full story. Our reporting included tracking down decades-old records, reviewing 1,000 pages of documents and conducting many interviews. Read more. |

Variations of those tactics extended to the University of Colorado. Among thousands of pages archived by the university and reviewed by CPR News are previously unpublicized reports from university police who in the 1970s were clearly watching student leaders of the university’s chapter of United Mexican-American Students (UMAS). The files show that university police monitored the UMAS meetings and demonstrations and reported directly to university officials on what they saw. They also worked to enforce bans on students who the university suspended or expelled over disputes related to UMAS and campus protests.

But the files contain no indications that undercover officers infiltrated UMAS or other student groups or that electronic surveillance was ever utilized to keep tabs on the activists.

It all makes for a story that is more complicated and nuanced than either side has told for much of the 50 years. The students had a lot of reasons to feel marginalized and discriminated against. The authorities had a lot of reasons for suspicion.

This is what happened to Los Seis, according to university, police, FBI and ATF files along with interviews of some of the people who experienced those events.

A turbulent time

A lot was going on in America in the spring of 1974. The Vietnam Peace Accords had been in effect for just more than a year, but troops were still adjusting to life back at home. House impeachment hearings were underway to examine President Richard Nixon’s role in Watergate. The trial of indigenous rights activists from Wounded Knee was underway. The Kent State massacre had yet to fade from memories.

And in Colorado, the Chicano movement was taking hold with Latino activists arguing for equal rights and better conditions. Marches were regularly held in Denver, where Corky Gonzales had a national following for his activism. Latino residents asserted themselves in politics, government, employment and education, demanding a seat at the table on issues that affected them.

“So it was sort of a national movement when a lot of quote Mexican Americans were finally fed up with a lot of the discrimination they were facing,” said former Denver Mayor Federico Peña, who as a young attorney represented several friends and family of Los Seis in a grand jury investigation following the bombings. "Some of the groups - not all of them - but some of the groups became very active."

Peña added that it was a violent time. People associated with the movement were killed in shootings from New Mexico to Denver, and there were bombings in Denver, Ft. Lupton and Alamosa, among other places, that federal authorities believed were carried out by Chicano activists.

Nicki Gonzales is a history professor at Regis University in Denver and the university’s vice provost for diversity and inclusion.

“I think one thing that Los Seis does: it gives us a window into early 1970s Colorado, Boulder, Denver,” said Gonzales. “We have the Chicano movement, we have the American Indian Movement, we have the Black Power movements, the Women's movement, I mean it was just this time of intense activism and idealism.”

At least on the surface, the University of Colorado at Boulder made an effort to embrace the Chicano movement by actively recruiting Latino students to the overwhelmingly white Boulder campus. A chapter of UMAS was formed on campus in 1968. A year later, the university created an equal opportunity program to provide scholarships and other financial aid to Latino students enrolling at the school.

But while the university was promising to provide aid to as many as 400 new Latino students a year, concerns among those students soon emerged.

Among them: in 1970 a rumor spread among students that the university board of regents was planning to freeze financial aid for minority students. In truth, the regents, in a secret meeting, decided to ask the legislature for additional funds for the program to ease the burden on the university. UMAS leaders feared that if funding wasn't growing, the number of newly admitted Chicano students would barely keep pace with attrition. Students demanded more transparency and consultation on decisions affecting them.

“Mr. Director, the Chicano students of UMAS are your responsibility,” students wrote to the UMAS director in 1973 after learning that they may have to repay some money from student jobs, in a memo found in the university files. “You are here for them, they are not here for you. It would be beneficial for all concerned if they were informed on issues directly affecting them.”

And there were other concerns. Students protested that open positions for student jobs were not being posted publicly, leaving some excluded. The university agreed to change that. They pointed out that lettuce served in the University Memorial Center had been harvested by taking advantage of low-wage Latino workers. The university agreed to find lettuce elsewhere.

Records show that rifts were developing among students too. Some of the leaders in the movement complained that not all the Chicano students were on board. One student called the university president’s office anonymously concerned that he was being coerced to join marches.

“All Chicanos not with us are against us and we should consider them our enemies also,” a university police officer quoted a speaker from a rally he was surveilling in April 1972. “At Regent Hall, he issued another warning - any Chicano not with us better be careful for we have ways of getting at you.”

But the disputes with the university regularly came down to money, according to the archived files from the university president’s office.

“Internal Audit Memorandum #125 indicates that receipts from the UMAS dance held on March 18, 1972, were not deposited with the university, but were used to establish the UMAS Legal Defense Fund,” wrote CU treasurer John E. Moreland to UMAS leaders in May of 1972. “The $615 evidenced by the paper signed by each of you must be returned for deposit by May 15, 1972.”

That series of disputes, large and small over nearly four years, eventually came to a head.

Students were angry that the university was choosing the leadership of UMAS and the equal opportunity program. They demanded more agency over their leadership and the money they were raising and better treatment by the university.

And two weeks before the twin explosions in 1974, they took over a university building, Temporary Building No. 1, to make their case.

A series of bombs

Tensions were rising in the community too. Earlier in 1974, after the Boulder School District chose to discontinue some bilingual education, a bomb was detonated in the middle of the night at Flatirons Elementary School. No one was injured.

Then bombs exploded at the Boulder courthouse and university police department while a UMAS dance was underway. Again, no one was injured.

Those followed previous bombs at the university’s motor pool, as well as at other Colorado universities. They seemed timed to detonate when people were not nearby and none had injured anyone. No demands were issued, and most of the crimes remained unsolved.

Then the big ones occurred.

The first was on May 27, 1974, at Chautauqua Park. A 1966 Oldsmobile was destroyed. Reyes Martinez, Una Jaakola and Neva Romero were killed.

Romero was popular and well-known in her hometown of Ignacio, a homecoming queen and a cheerleader, she dreamed of becoming an educator. Martinez, a recent graduate from CU law, had a passion for representing “the poor oppressed Chicanos,” according to an obituary in the campus Chicano newspaper, El Diario de la Gente. Jaakola, a CU double major, grew up in a small town in Minnesota and was the girlfriend of Martinez.

“Investigation of the crime scene revealed that dynamite was the explosive used and that a pocket watch was apparently being used as a timing device,” according to an FBI report now in university files. “Preliminary investigation has revealed [Neva Romero] purchased at least one pocket watch on May 26, 1974 or May 27, 1974 at a Woolco Department store in Boulder and at about the time of purchase told another party of the presence of a bomb in her vehicle.”

A part of the pocket watch was found embedded in the remains of one of those killed. Without evidence, the ATF speculated that the students intended to destroy Temporary Building No. 1, where the student takeover was nearing an end.

Two days later, a second explosion in the parking lot of the Burger King on 28th Street in Boulder killed three more, Florencio Granado, Francisco Dougherty and Heriberto Teran.

Granado was a former CU student, past president of UMAS, and a volunteer worker for the United Farm Workers. He published a small newspaper for North Denver, and after his death, his friends worked to put out the last issue. Teran was from Texas but was working as a social worker in Denver. Doughtery, an aspiring doctor, was a friend of Teran from back in Texas and arrived in Colorado the same day of his death.

A fourth man, Antonio Alcantar, served in Vietnam as a Marine and had received two Purple Hearts. He lost his leg in the explosion but survived. He died in 2002, according to one activist.

“A search warrant executed at the Alcantar residence produced a trigger device for a bomb, batteries, a Westclock pocket watch and surgical gloves,” according to an FBI report. “Dynamite residue was found on the gloves.

Another search warrant at the home of the owner of the second car that exploded turned up a chapter of a manual on explosive devices. “A review of this chapter shows many types of improvised explosive and incendiary devices. Page 315 depicts the use of a watch with a battery and explosive charge, the same type devices believed to have been used in both Boulder bombings,” according to the ATF report.

Broken hearts and deep suspicions

After the explosions, the grief among UMAS members and others on campus was palpable.

“We were dying of a broken heart,” said Freddie “Freak” Trujillo, in the documentary Symbols of Resistance. Trujillo died in 2020. “We hugged each other and cried and screamed and hollered and did everything that we had to do to let go of that anger and that pain.”

Boulder police very quickly theorized that both cars exploded as the activists were assembling bombs inside. That was based on the condition of the bodies, the damage to the vehicles, the results of the initial searches of the activists’ homes, and interviews with friends of the activists who said they had either seen their friends with dynamite or heard them discuss the possibility of planting bombs.

But that was far from the end of the investigation. Federal agents, local Colorado police and sheriff’s deputies interviewed about 150 people, collected evidence from the two bombing scenes, analyzed chemical samples, and executed additional search warrants. A grand jury was convened in Denver to hear evidence in the case, but its racial makeup was challenged and several people called to testify refused to cooperate, in the view of authorities. Grand jury proceedings are secret, so the reasons no one was indicted, or even if the jurors were asked, is unknown. But, with all but one of the people in the cars killed, no one was charged in the explosions. The Boulder district attorney at the time also declined to prosecute the sole survivor of the blasts on state charges.

Dave Stolz retired from the CU police department in 1997 as a detective lieutenant. When Los Seis became news in recent years Stolz considered speaking out against coverage that painted the deaths as unsolved — he was going to write a letter to the editor but decided against it. He didn’t want to inflame tensions, and he spoke publicly only after CPR News independently contacted him.

“The truth, from my point of view, given the facts I know, is that these six people died as they were attempting to set bombs that they were going to plant at buildings, maybe on the CU campus, we weren't sure where they were targeting,” said Stolz, in an interview at his home in Colorado. “That's the truth I know.”

It was the search warrants at the homes of the victims that provided the most clear-cut evidence Los Seis were making bombs, said Stolz.

“And I do remember finding stuff that was evidence of bomb-making there,” Stolz said. “And I was there with some sheriff's detectives.”

Stolz is among just a handful of people with connections to the bombings or investigation who remain alive today. Two Chicano activists from the time contacted by CPR News declined to speak on the record out of concern that the story would fail to address the full sweep of discrimination they faced on campus and across the state.

Almost immediately after the six were killed, some of their friends and supporters offered alternative theories for how it happened, according to their interviews with FBI and ATF agents. Maybe white supremacists threw firebombs into one or both of the cars. Maybe enemies among the Chicano movement had killed them as a result of an internal dispute at UMAS. Maybe someone had nefariously replaced the correct bomb-making instruction manual with a handful of pages that were incorrect and led to the explosion.

In a statement to a campus Chicano newspaper, El Diario de la Gente, on June 11, 1974, UMAS, Chicano Law Students, and the Farm Labor Task Force wrote that the bombs “may have been planted in the cars and that the explosions may have been a work of a third party conspiracy to murder elements active in El Movimiento.”

In each case, agents dutifully took down the possibility, but no evidence for any of those alternatives ever emerged.

On the contrary, the few witnesses to the bombings saw no one else anywhere near the exploding cars, they told agents. The sole survivor of the second bombing made some initial statements about fearing that others in the movement would be angry at him, then apparently declined to cooperate with investigators. No record of an interview with him is among the FBI and ATF reports.

For many, the federal agents’ conclusions are irrelevant.

“It's also important to put that report into its context and so if you look at the record of local law enforcement of FBI of the ATF at that time you see a very complicated history as well and a very complicated violent history of those institutions with the Chicano movement with the Black civil rights movement and so its really you can't fully understand that report or even see it as credible in light of that of that history,” said Gonzales, the Regis professor. “I have not read the ATF report in its entirety I've just read the first few pages and I just know the context in which it was written and sort of the tone and the words that were used to describe the activists.”

By today’s modern forensic standards, the investigation into the bombings appears amateurish in spots. In both cases, citizens were still in the area of the explosions soon after they happened, though there is no indication they contaminated any evidence. Handwritten drawings contained in the reports are little more than estimates of where the debris scattered rather than today’s precise measurements. In their reports, agents occasionally get the date of the second bombing wrong and some names are misspelled.

Graduate student renews interest in the cases on campus

It was a grad student at CU Boulder in 2019, Jasmine Baetz, who helped shine a light on Los Seis by creating a sculpture of the six who died.

Baetz was inspired by a documentary, Symbols of Resistance, which recounts the Chicano movement in Colorado and New Mexico and focuses partly on the bombs that killed Los Seis.

“To learn about their activism, because I didn't know about their activism, and then also these deaths all at the same time was horrific,” said Baetz, who also created the second memorial that will be dedicated Tuesday, May 28. “The erasure, or the willful way the University and the town and whoever else had gone about not talking about this history functioned both to leave this huge wound around this violence and it also functioned to silence all of that activism.”

On Tuesday evening, about 100 people gathered in Boulder at the intersection of 17th and Pearl Streets, in front of a bank and a half block from a Michelin-starred restaurant, Frasca Food and Wine.

They were there to unveil a second sculpture dedicated to Los Seis, and, like the one on campus, also created by Baetz. The piece, El Movimento Sigue (The Movement Continues), bears similarities to the sculpture on campus, but is a more expansive embrace of the movement for justice.

"The tiles reference the solidarity work between the United Mexican American Students and the Black Student Alliance at the University of Colorado-Boulder in the 1970s," reads a plaque accompanying the sculpture.

Speakers recounted the lives of Los Seis and the struggle for recognition, education and equality. In the 1970s, UMAS argued that the student body should reflect the state's population, But 50 years later, the university's percentage of students described as "Hispanic/Latino" was at 12.6 last fall, still well behind the state's 22.52 percent Hispanic population. Speakers at Tuesday's event including Boulder's city manager, a Boulder City Council member, Baetz and the sister of Una Jaakola described the struggle for parity as ongoing.

"May we never be idle in the face of injustice," said CU graduate and former UMAS member Mateo Manuel Vela, who was on campus as the sculptures were being created.

There was no suggestion by any speaker, no mention at all that Los Seis might have died by accident while making bombs.

At the back of the crowd, Boulder District Attorney Michael Dougherty stood quietly, applauding the speeches in between shielding his eyes from the setting sun.

Dougherty was asked: Did the presence of the district's chief law enforcement officer at the event indicate that, 50 years on, it no longer matters how Los Seis died, but is more appropriate today to focus on the injustices they fought? "I'm here to honor the memory of those who were lost, and in respect for their families," said Dougherty, who acknowledged that he has had no reason to review the long-closed investigative record in the cases. "It is just hard to imagine a Boulder in the 1970s where six people could die in a pair of bombings. I thought it was important to be here."

CPR Investigative Editor Chuck Murphy contributed to this report.