Kate Showalter knew that cancer might come for her, ever since it took her mother’s life in 2002.

She made plans for it.

“I always said that if I ever got cancer, I would tell my daughter,” the 39-year-old said in a recent interview. “I would tell her things.”

Showalter was a teenager when her mother, Radene, got sick. And while she was close to her mom, Showalter only learned the severity of what was happening from her father, or by eavesdropping.

“I was angry that she didn't tell me the truth,” she recalled. “I was angry that she left me.”

Twenty years later, in 2022, Showalter was diagnosed with cancer, too. As it has advanced, she’s seen the story from a mother’s perspective, in all its terrifying detail: the pain, the mental fog that comes with chemotherapy, and the unanswerable questions: Would she live? And what would she tell her own little girl, Rúni, who’s 5 now?

“All of a sudden, I'd start crying in front of her,” Showalter said. “I would think about the future, and missing out and everything like that — instead of being present right then and there.”

This harrowing fear and worry seemed to spread like the cancer cells themselves. But Showalter is determined that her story will go differently than her mom’s.

She’s trying treatment options that patients before her never had — for her cancer, and for her mind.

Could psilocybin change a young mother's cancer journey? Inside Colorado’s major psychedelic study

Story by Andrew Kenney

Listen to the podcast version of this story here, or scroll to continue reading.

Showalter recently joined a new wave of research into psilocybin, the key psychoactive compound in psychedelic mushrooms.

She’s among the first patients in one of the largest-ever studies of the psychedelic drug, happening now at the University of Colorado.

The medical trial explores a part of cancer that you don’t always see in the movies: the angry, impossible emotional struggle that doctors call “existential distress.”

Showalter signed up in the hopes that combining therapy with an intense psychedelic experience would break anxiety’s grip on her precious time. She wanted to live more freely, for however long she might have with her husband, Michael, and their daughter.

“I don't want to die, but my main concern is Rúni,” she said on an afternoon in April, sitting for an interview in her family’s sunlit Denver home. “I don't want her to go through what I went through with my mom.”

Eventually, up to 200 cancer patients in the experiment will follow Showalter’s path, taking the same regimen of talk therapy and a large dose of psilocybin.

Showalter’s story is one of the latest data points in the scientific question of whether psychedelics can change how people relate to death itself — an idea that has become a promising new area of focus for Western medicine.

The former head of the National Institutes of Health, Francis Collins, said of psychedelics in 2021: “We’ve begun to realize that these are potential tools for research purposes, and might be clinically beneficial.”

Trials like the one Showalter is enrolled in aim to finally provide proof about the effects of a substance that was cast aside for decades. The NIH did not fund these trials until just a few years ago. Now, with $3 million in federal grants, CU’s study is one of the largest and best-funded projects among dozens of psilocybin trials that have begun in recent years.

“I do think that is the future of cancer care, and hopefully something that we could look forward to in the next five or 10 years,” said Dr. Brian Barnett, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the Cleveland Clinic, who has closely followed psychedelics research but isn’t involved in the project.

One scientist’s 50-year wait

The Colorado researchers hypothesize that psilocybin may help with a profound problem for late-stage cancer patients.

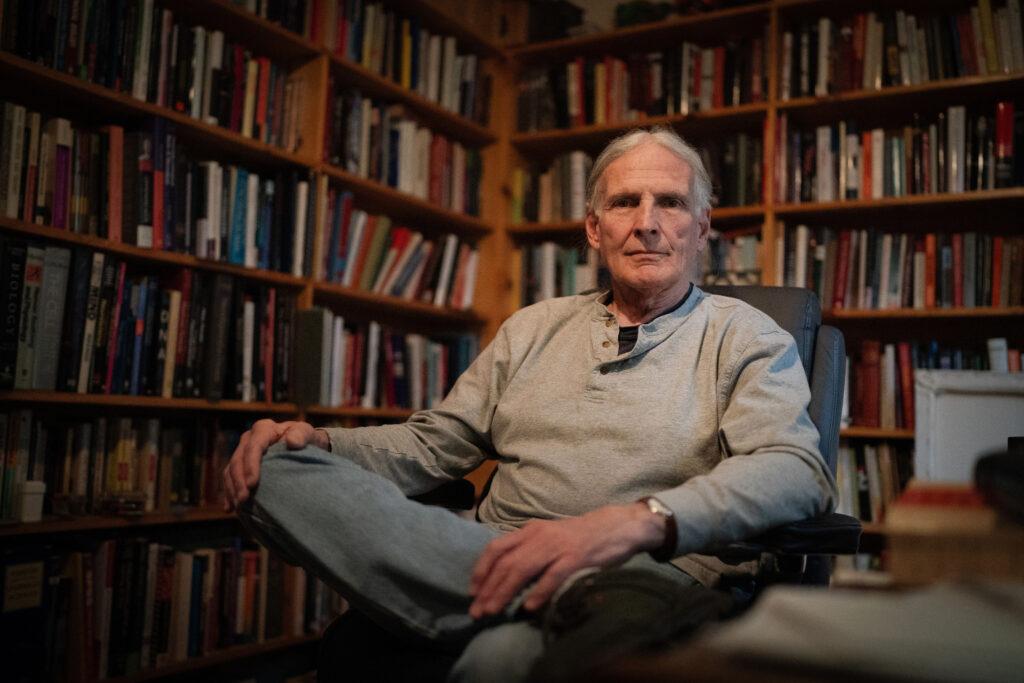

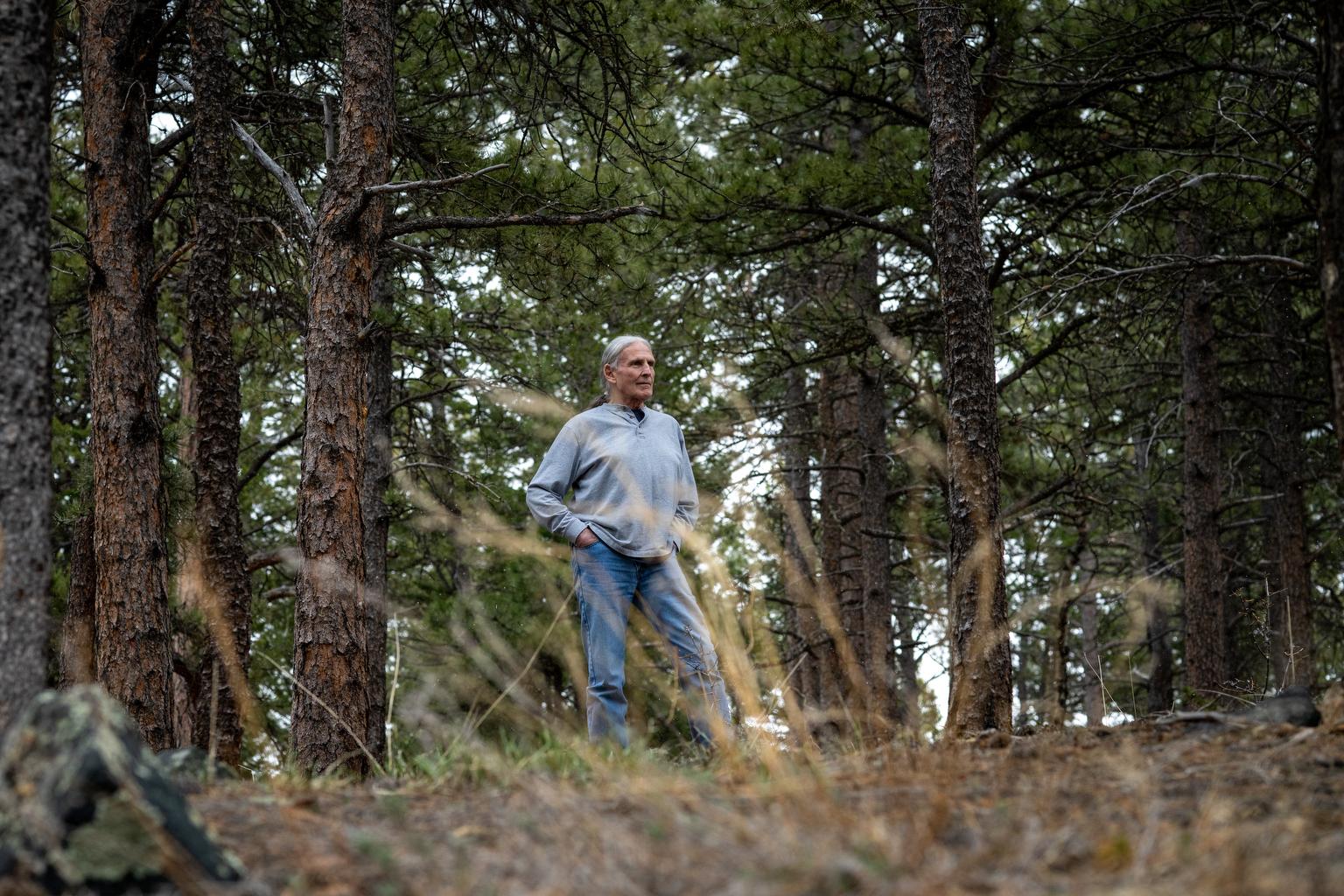

“They’re facing the end. And to be able to face it in a way that was maybe without fear and guilt… I thought that was something that was very valuable,” said Jim Grigsby, a neuroscientist who is one of three researchers leading the project.

This idea that psychedelics could help people confront death is not new, and Grigsby has been waiting a half-century to try an experiment like this.

“It's been there all along, and a lot of people knew it, but couldn't do the work,” he said.

In the 1970s, Grigsby was a wayward undergraduate at the University of Kansas. He had some academic false starts, dropping out to work on jackhammer crews and loading docks. But a revelatory experience with the psychedelic drug LSD changed that.

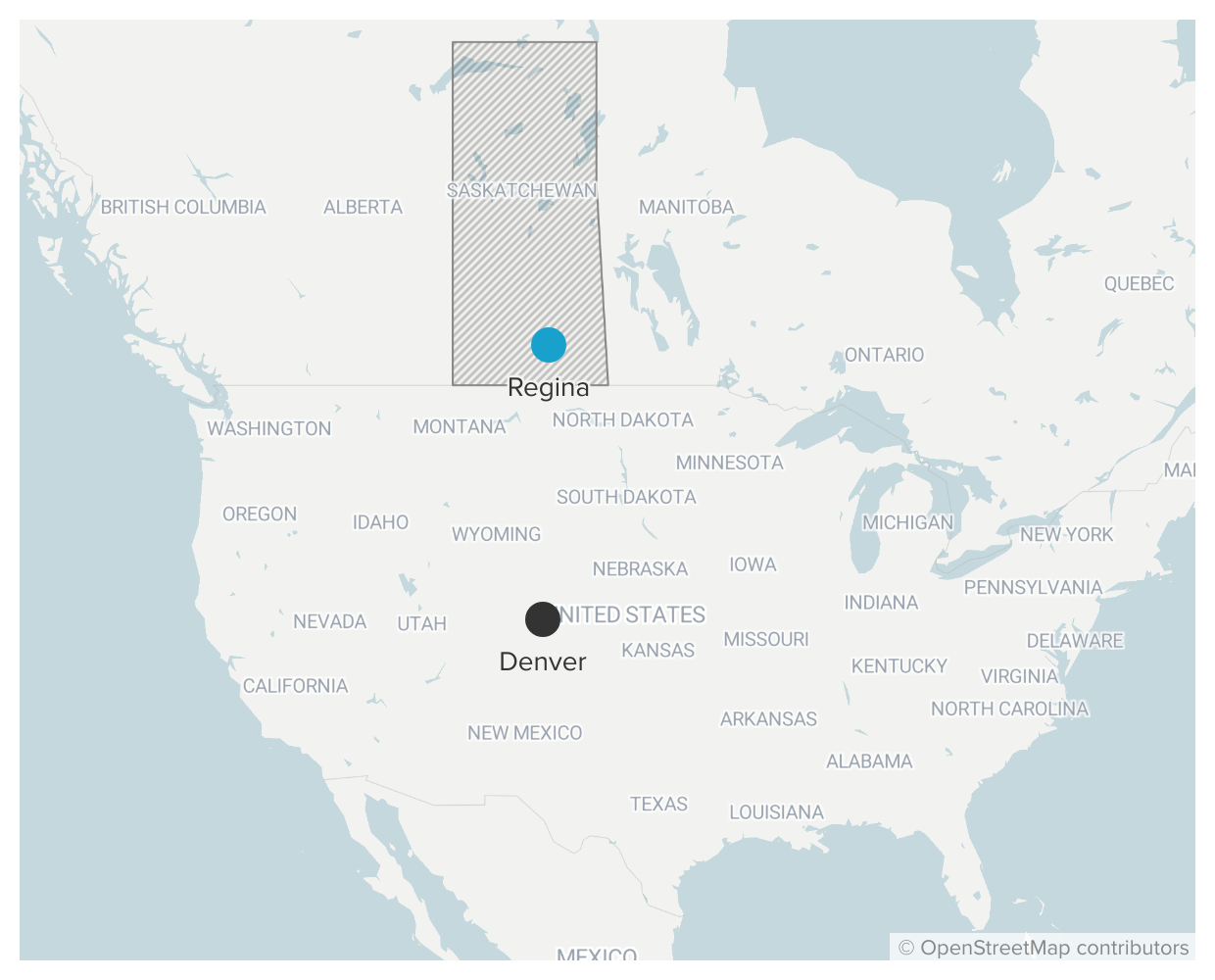

After his mind-altering experience, he decided to study the brain itself. And he knew the place to do that was about 800 miles north, in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan.

Saskatchewan had emerged as a free-thinking center for psychedelics research, where academics studied the drugs’ potential therapeutic effects for conditions like alcoholism, and used them to study schizophrenia.

“You had a number of very committed researchers who were also quite prolific in terms of their networking and correspondence,” said Erika Dyck, a historian at the University of Saskatchewan. Among them was the English doctor Humphry Osmond, who came to Canada because of its welcoming research environment. While he was there, he coined the word “psychedelics.”

Death was an early focus of some of those so-called “psychedelic pioneers” in Saskatchewan and beyond. The author Aldous Huxley, who was friends with Osmond, took LSD in the final hours before he died of larynx cancer,

“Suddenly he had accepted the fact of death; he had taken this moksha medicine in which he believed,” wrote his wife, Laura Huxley, in a letter, referencing a fictional psychedelic drug in one of Huxley’s novels. Huxley’s widow asked whether “his way of dying” could benefit others, too.

The young Jim Grigsby was particularly drawn to the 1960s work of Eric Kast at the Chicago Medical School, who found that LSD offered significant pain relief and improved morale to cancer patients.

Some of these early Western experiments drew from the knowledge and practices of Indigenous cultures that have long used psychedelics. In Saskatchewan, a local community contributed to the white researchers’ ideas about how to design psychedelic trials.

Concerns about appropriation

As money for medical research with psychedelics grows, so does concern about whether Indigenous practitioners and expertise will be left out and their traditions monetized by Westerners. A group of scientists, practitioners, lawyers and other activists recently laid out a guide in the science journal Lancet for how Western medicine could achieve more representation in the research, as well as respect for Indigenous traditions and reconciliation for the past. You can also read more about the history and what's being done to correct it here.

The Western scientists suspected that psychedelics, with their seeming ability to reorient the mind, could help people to find new meaning in the face of the unknown. Grigsby wanted to be part of it, so he applied to the University of Regina and later loaded up his blue Datsun station wagon to drive north into Canada.

But there was something he didn’t quite grasp that summer in 1972.

Amid President Richard Nixon’s “War on Drugs,” the governments of the U.S. and Canada were cracking down on psychedelics like mushrooms and LSD, which quickly diminished academic and pharmaceutical industry interest in the drugs.

Also, governments had put much tighter regulations on medical trials overall, after the failure to properly regulate the drug thalidomide caused thousands of babies to be born with anomalies like missing limbs.

As a result, as Grigsby arrived in Saskatchewan, he learned that the psychedelic revolution in Western medicine was all but over.

“As far as I knew, the door to psychedelic research was permanently closed,” he said.

The unanswered questions

One of the Canadian researchers, Duncan Blewett, gave Grigsby some advice as the young man reassessed his future: Stick with science. Maybe the door for psychedelics research would reopen one day.

So, he waited. Grigsby completed his master’s in psychology in Canada, and later came to Colorado, where he completed another master’s and a Ph.D. at CU Boulder and established his career in neuroscience. In 2001, he was part of a team that made a major discovery of a neurodegenerative disease, FXTAS, that had previously been mistaken for a form of Parkinson's.

All along, he wondered how psychedelics would fit into his work.

Living in a rustic cabin in the foothills outside Ward, he continued to experiment with the drugs on occasion. He was fascinated by questions that went back to his early college experiences.

Some were profound: How had it produced such vivid feelings of contentment? Others were goofy: Had LSD really turned him into a football-catching phenom one time? (The baseball player Dock Ellis once pitched a no-hitter while on acid, so perhaps that question isn’t so goofy, after all.)

Grigsby thought that psychedelics could reveal something deeper about humanity, tying together his many professional interests.

“I think I was trying to understand the nature of myself and of selves generally,” he said.

But as decades passed and the old research grew dusty and dormant, Grigsby began to wonder: Would psychedelics ever be more than a personal project?

“It was kind of lonely … You had to keep it quiet,” he said. “You’d be branded as a nut, or just a dangerous person … So nobody at work knew. It was a secret.”

Medicine for death

The psychedelics research of the 1950s and ‘60s wasn’t just exploring new drugs. It was also at the edge of another modern movement: end-of-life care.

Before the 1950s, Western medicine focused primarily on the prolonging of life, not the easing of death. That began to change with the hospice and palliative care movements, including the early experiments in LSD therapy for cancer patients.

“[D]ying care claimed a special interest for these early psychedelic thinkers,” Dyck wrote in a paper. Aldous Huxley had specifically suggested that LSD could be administered to people with terminal cancer “in the hope that it would make dying a more spiritual, less strictly physiological process.”

Even while research with psychedelics and cancer patients was cut off, palliative and hospice care blossomed. The first modern, dedicated hospice centers opened for the care of dying people in the United Kingdom in the late 1960s and the U.S. in the 1970s.

“Only in the latter half of the twentieth century has the idea begun to be accepted that death fits into a clinical category of its own, complete with its own spiritual needs, specialized care teams, and a philosophical acceptance of human mortality,” Dyck wrote.

Today, those two threads — psychedelics and care for the dying — are meeting once again. The new wave of psilocybin trials began in 2006, and a study in 2011 was the first recent look at whether psilocybin could offer relief from existential distress.

The 2011 study involved a dozen people with advanced-stage cancer. They received only “modest” doses of psilocybin, but still found a “sustained reduction in anxiety” and improved mood in the months afterward. A similar study in 2014 also found promising results.

In 2016, researchers at New York University and Johns Hopkins University published two more papers, examining psilocybin’s effects on a total of 80 more patients between them. Both found significant improvements lasting six months or longer for up to 80 percent of patients.

The results caught the eye of another researcher at the University of Colorado, Dr. Stacy Fischer. She learned about the psilocybin cancer research from a Michael Pollan article in The New Yorker.

Fischer had never tried psychedelics, nor thought much about them. But she had to know more.

“We had nearly nothing [to treat existential distress] and the psychedelics were the first promise of something that could really shift that feeling of demoralization, hopelessness, and despair,” she said.

Fischer is an influential figure in palliative care. That began, in a way, with her own mother’s death from cancer, which happened when Fischer was still in medical school. She has since spent her career trying to ease the process for others.

“It is this profound period that we all are going to face, death,” she said. “And to be able to help people prepare in the best way possible… is something that's really important to me.”

‘Well, it's about time.’”

In 2018, Fischer’s newfound interest in psychedelics brought her together with Grigsby, her CU colleague, who thought the time was finally ripe to pursue research funding. Grigsby and Fischer connected with Stephen Ross at NYU, a lead investigator on one of the earlier studies.

They decided to go big.

At the time, the U.S. was collectively reconsidering the War on Drugs and the destructive effects of incarceration on tens of thousands of families. Meanwhile, backlash to addictive opiates drove interest in alternative medicines. In 2019, Denver voters made their city the first in the nation to decriminalize psilocybin. In 2022, a similar law passed for the entire state of Colorado.

Those legal changes in Colorado had no direct effect on medical research. But the broader societal shift coincided with changing attitudes at the NIH, the federal agency that is a principal funder of medical research.

When the Colorado team first applied for federal funding, they faced plenty of skepticism from reviewers. But over the course of 18 months, that resistance seemed to thaw.

Fischer was at home in Denver when she learned that they would almost certainly get their funding.

“I was speechless. I was so excited. I think I called both Jim and Steve right away and no one picked up. And so I was left on my own in the house with this really exciting news, just kind of whooping and laughing,” she said.

With millions of dollars and a multi-year span, it would be one of the largest psilocybin trials yet.

“That's a big trial,” said Dr. Barnett, who has studied NIH funding for psychedelics. “And I think that says a lot about the confidence that the National Cancer Institute has in this team of researchers in particular and in this particular avenue of research.”

When Fischer finally got a hold of Grigsby, his feelings were mixed.

“I was very excited, but I was also kind of irritated,” he said. “I thought, ‘Well, it's about time.’”

He’s not the only one who had been waiting. When this experiment first got going in August 2022, the emails from potential participants came streaming in — one after the other.

“That was far, far greater interest than I had ever anticipated,” Fischer said.

Among them was a young mother looking for answers.

Why Kate Showalter joined the experiment

Before joining the trial, Showalter had tried psychedelic mushrooms recreationally a couple times. The first time, she was 22 — watching “The Sword in the Stone” with a friend.

“We were on the second floor, and it was this huge thunderstorm,” Showalter recalled. “All the cars looked so tiny down on the road and the people looked tiny, the trees. It was hilarious.”

She never felt much of a need to try psilocybin again. She grew up. She married Michael, and five years ago, Rúni was born. The family bought a cozy house in Denver and began filling it up — with music, gemstones, instruments, and art. The walls are lined with Showalter’s paintings, including figures and landscapes. The paintings are never quite done; she’s always liable to pull one down and work on it.

“I don't see how I could live in a place that wasn't funky,” she said.

Showalter got her green thumb from her parents. She’s a natural, able to coax life from any pot. But as she looked over the new blooms that cover nearly every corner of her sunroom one recent afternoon, her frustration crept in. She couldn’t remember the plants’ names.

“That's the most difficult, with chemo brain,” she said. “I can picture it in my mind, and I can't bring them up.”

Two years ago, doctors told her that her cancer was terminal — meaning that they could continue to treat her, but that they didn’t expect her to survive. She has a cancer known as carcinogenic ex pleomorphic adenoma, and it made a rare, life-threatening metastasis, spreading from its origin point in her salivary gland, down to her lungs.

Rúni was a toddler when Showalter got sick, but already intuitive. Lying together in bed one night, the little girl asked if her mother would die.

Since then, Rúni has come with Showalter to her appointments, and been her cheerleader through dozens of rounds of chemotherapy and radiation. She lends out her favorite stuffed animal, a hedgehog named Ramen, to help her mother smile.

With Rúni’s support, Showalter has continued to fight the cancer itself. She’s enrolled in a novel treatment from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, including doses of the immunotherapy drug Keytruda. She hopes — she believes, actually, and Rúni does too — that she will survive.

But Showalter also sought help to ease her existential distress. It was manifesting constantly at home. She would sometimes burst into tears trying to get Rúni’s socks on.

“Before cancer, I had this endless well of patience for my daughter. And when cancer came, I lost that. So, I wanted to see if there was something I could do to have that go away,” she said.

When her oncologist mentioned a psilocybin study at the University of Colorado, she knew she had to apply. She’d be one of dozens of patients — hundreds, eventually — turning to Jim Grigsby, Stacy Fischer, Stephen Ross and their team.

Whatever life would be, she wanted to live it, and she thought psilocybin might help.

Inside the experiment

Each patient begins the experiment with a psychological screening. Then, those who are accepted go through hours of talk therapy and psychological assessments, helping the researchers to establish a baseline and to prepare patients for their psychedelic experiences. A patient gets just one dose of psilocybin, followed by more therapy over a period of weeks afterwards.

On each patient’s “dosing day,” they report to a gleaming medical office building at the CU Anschutz campus, where they receive either a supervised dose of psilocybin or a placebo drug. Those who receive a placebo, which contains niacin, can return later to take psilocybin instead.

The drugs are kept in a highly secure closet on the sixth floor. It’s a small, brightly lit room lined with locked cubbies and a locked refrigerator.

“We’re being videotaped right now,” explained clinical pharmacy specialist Jacci Bainbridge on a Wednesday in March. “So there's somebody watching us, because these are Schedule I products.”

The drugs must be carefully managed, even though the same types of substances are readily available in Colorado now. The storage facility at the hospital is so secure, in fact, that the pharmacy team struggled to get the drug cubbies open on the day CPR News visited.

When the team finally opened the door, they took out a single white pill. Neither the practitioners nor the patient would know if the pill contained psilocybin or just the placebo. The psilocybin is synthetic — produced by a supplier via chemistry, with no mushrooms involved.

Each patient takes their dose in a small room with a few pieces of simple, comfortable furniture. A medical office building isn’t the platonic ideal of a place to trip, so the researchers had to figure out some adjustments — how to position the couch for comfort, how to keep patients away from the building’s agoraphobia-inspiring atrium while taking them to the bathroom, how to cover up all the mirrors.

But none of that was Showalter’s concern when she arrived for her dosing day last August. She was just anxious for relief.

“It has been debilitating, this anxiety. It's been a constant companion,” she said.

Kate Showalter’s dosing day

The researchers gave Showalter a choice of two vessels to hold the pill: a wooden bowl, or a beaded, colorful one. She chose the beads. Then she swallowed the pill, hoping that she had gotten the psilocybin.

“Thirty minutes passed, and my heart started racing, and I was like, ‘Oh my goodness, maybe this is happening.’ But then — it didn’t,” she recalled with playful drama in her voice.

It was a little disappointing, but she didn’t mind. She took a four hour nap instead, monitored the entire time by a therapist.

“They filmed the whole thing for the study. They got me taking a nap, and then I ate an apple, and that was it,” she said.

Her opportunity to take the real psilocybin dose would come six months later, in February 2024.

In the meantime, something surprising — and wonderful — happened. Showalter’s doctors told her that she was making progress in the fight against the cancer itself. The other experimental treatment seemed to be working. In at least one test, the cancer had become undetectable.

The good news wasn’t certain, though. She’s still sick with a very dangerous cancer.

The doctors said there was a “50-50 chance that it will come back,” Showalter said. “But they don’t know, with my cancer, because this has never happened before.”

Those odds left her on a knife’s edge between two futures, still wondering how long she’d have with Rúni — and still wondering how her daughter would remember her.

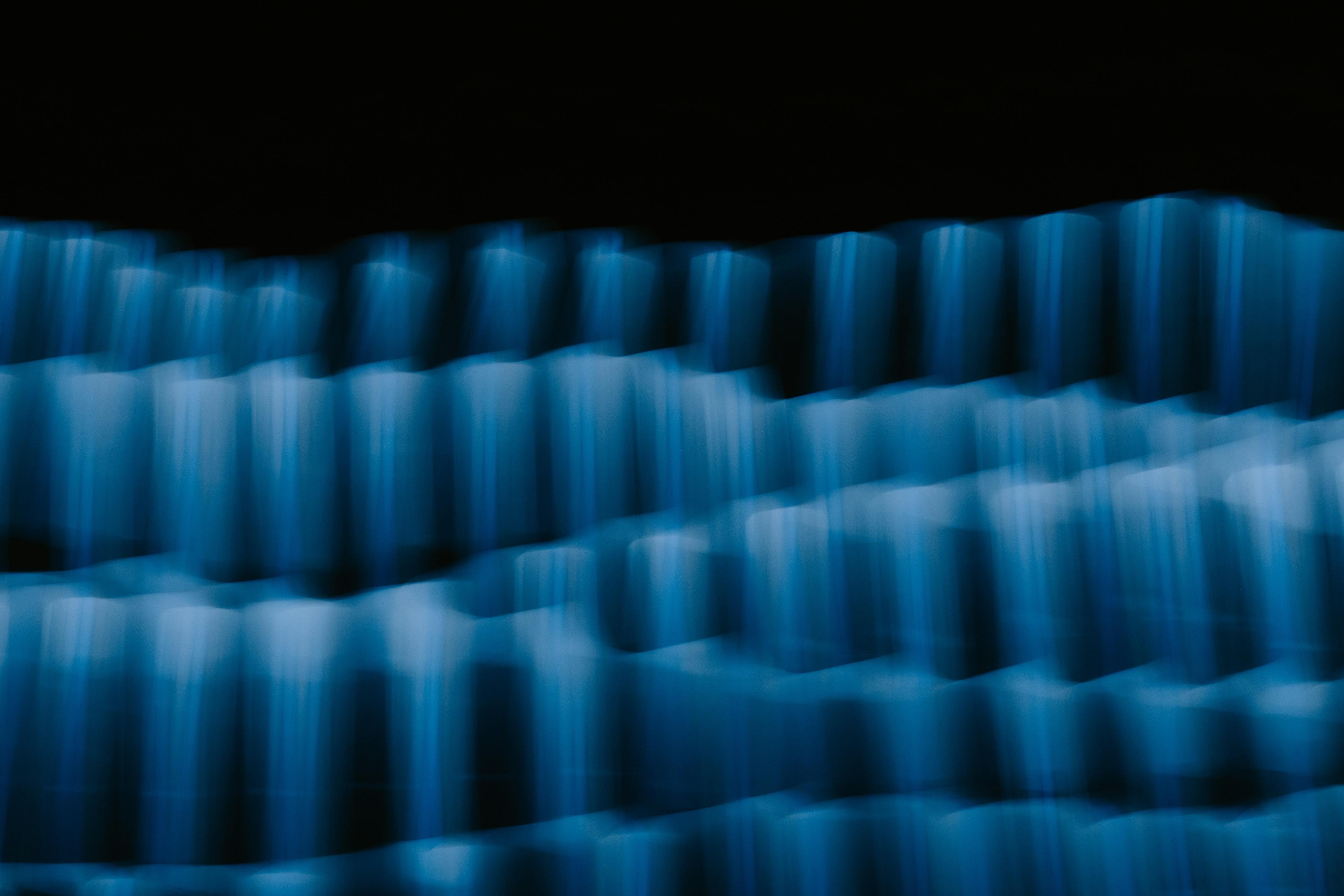

So she went back to the medical building in Aurora in February, walking past the soaring atrium and riding the elevator to the fifth floor. She took the white pill and drank some ginger turmeric tea. After a few minutes, a new sensation crept in through her fingers, and the therapist said it was time to put on the eyeshades and the headphones. A playlist of calming, trippy music came on.

Then, Showalter laid still for five hours straight.

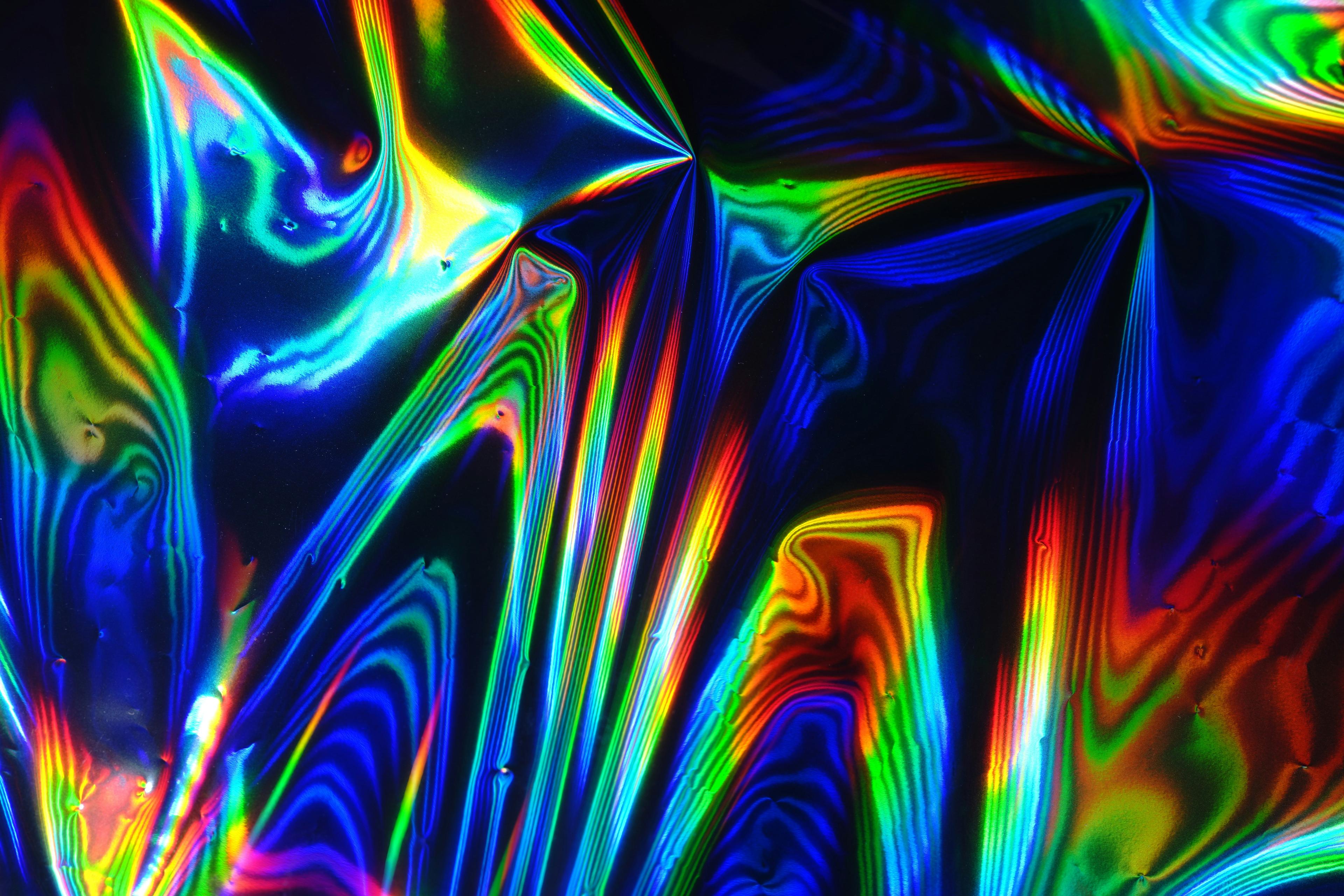

“All of a sudden,” she recalled, “these rainbow, beautiful colors started to seep in. And then they turned into geometric patterns and fluid, just chaotic everywhere, but beauty in the chaos, and geometric fluid going into wormholes,” she said, the memory clearly tangible. “The colors would come from in between my eyes, or they would rush up from below, or come from above and come through me.”

Amid that kaleidoscope of light, she could sense a dullness on the left side of her jaw, where the cancer had started a couple of years earlier.

“The colors were a little more dull. I didn’t quite understand that,” she said. “So with my breath, I could send the color, the rainbow, beautiful colors, over to that side of my visions.”

It was like she was coming to terms with the cancer. Other patients have reported a similar sensation of confronting cancer — or death itself.

And then, in an abstract way, she felt her mother’s energy draw near. Twenty years after the death that had splintered her family, as Showalter stared at her own mortality, she felt an echo of Radene’s emotions. Part of the power of psilocybin, Grigsby has suggested, may be in reassessing and changing our connections to past memories.

“I was with her anger and her sadness and my anger and sadness, her pride in me,” Showalter said. “It was so beautiful. So beautiful.”

She cried throughout the experience. It was a “total loss of control,” she said — a surrender that led to acceptance. As she came back to reality, she felt “wonder, tranquility, just a sense of connection with everything, and a sense of wellbeing.”

When she got home and saw Rúni, Showalter cried again. And the feeling lasted. A month after the trip, she said cancer still scared her, but her dread and anxiety hadn’t returned. Her patience for Rúni had come back, too.

“I don’t know how long this will last,” she told me. “I don’t know when the anxiety will come back. But it’s just been such a blessing.”

What we know so far

Participants in the trial, including Showalter, attend therapy appointments in the weeks immediately after their psilocybin dose. Research suggests that those weeks offer the best window for therapy to be effective.

“That's where real growth and change can occur. And when we can get out of these patterns or cycles or spirals that are not serving us well,” Fischer said.

She and Grigsby stress that they’re still in the early stages of their trial. The experiment may ultimately prove or disprove — or leave unanswered — their hypothesis about the potential of psilocybin at the end of life. If it does prove positive, Fischer said the large scale of their trial could make insurers, including Medicaid and Medicare, consider covering the therapy.

In addition to treating existential distress, Grigsby wonders whether this therapy could help with chemo brain – the phenomenon that made Showalter forget the names of her plants. He thinks, too, of people with FXTAS, the syndrome he helped discover. Scientists never came up with a cure — but what if psilocybin could help people accept the fact that they have a chronic illness?

“The thing about psychedelics is, we haven't even begun to touch what they can tell us,” Grigsby said.

There are limitations to psilocybin. Often, people hope for a miracle or a mystical experience that they won’t get, Grigsby said. Psilocybin simply won’t have the same effect on every patient.

“I think a lot of people come into it thinking, ‘Oh, this is great. I'll take some psilocybin and I'm going to feel so much better. I'll feel kind of like a new start in my life,’ Grigsby said. “And it doesn’t quite work like that.”

While the positive effects can sometimes last a year or longer, they may be far more limited for others. In the worst cases, a trip can turn into a nightmare — making it all the more important that this experiment is happening with trained clinical supervision.

“Not everyone's dosing session is some kind of spiritual enlightenment. Sometimes, people have really difficult experiences and don't want to be in that moment anymore,” Fischer said.

As they continue their work, the researchers are also thinking about how it relates to Indigenous cultures and experiences. They acknowledge that psilocybin, specifically, was taken from a Mazatec healer in Mexico by a white banker and explorer, with ruinous results for the healer.

Fischer said that her focus is on examining the substance by Western medical standards, providing answers and evidence about whether it should become part of treatment.

“I am very concerned around… appropriating these traditional practices into this study,” she said. “And I don't have answers yet. It's something I'm still thinking about and exploring personally.”

The years ahead

Grigsby is in his 70s now, and this project will be a central focus in the closing years of his career.

It feels “a bit weird that it took this long to get to something that I had hoped to be able to do from the beginning,” Grigsby said. “But at the same time, it is kind of cool just to get there… I'm going to do it for as long as I can. Until I drop, I suppose.”

It will take years for Fischer and Grigsby’s study to play out. Meanwhile, other researchers are also amassing data and forming theories about whether psychedelics could potentially help patients with anxiety, depression, PTSD, addiction, chronic pain, autoimmune disorders, and other conditions.

In a way, this research is arriving just in time for patients like Showalter. But she’s left thinking about the cost of those decades of delay. If psilocybin is really effective, could it have helped her mom, too?

“I wish she had this opportunity. I wish that the war on drugs really didn't come to fruition. We’re so far behind what we could be, what could have been,” she said.

She didn’t dwell on the question long, though.

On that April afternoon, we brought our interview to a close because she had somewhere to be. She was picking up Rúni from kindergarten, about a 10-minute walk down city sidewalks lined with new spring buds.

“Oh, I hope it lasts,” Showalter said. “I don’t know if it will, but I’m so hopeful.”

She found Rúni on the school playground, wearing sparkly red shoes, red tights, and a black and white dress — an outfit she had picked out herself.

After a little coaxing, Rúni hopped on her scooter. Mother and daughter headed toward home, stopping to look at rocks and flowers and all the curious things in the world. When they arrived, Rúni opened the gate, eager to show off her bedroom, her stuffed animals, her pink-and-blue betta fish.

“Wanna see something very cool?” she asked gleefully.

Her mom smiled. This was their life.

Want to learn more about the study?

Who it’s for: People with late-stage or advanced cancer

The goal: Studying the effect of psilocybin and a placebo, along with psychotherapy, in the treatment of anxiety, depression and existential distress among patients.

Number of patients: Up to 200

Where it’s happening: CU Anschutz and New York University

The drugs: The psilocybin is administered as a pill with 25 mg of the substance, considered a “high” dose. The active placebo is a dose of niacin.

The treatment: Patients receive six hours of preparatory psychotherapy before dosing, followed by eight hours of integration psychotherapy in the weeks following.

What it’s measuring: Changes in outcomes on scales of anxiety, depression and demoralization, and others related to cancer, mortality and general outcomes

Duration: 2022 through as long as 2027

How to enroll: Talk to your oncologist, who can work directly with the study coordinators

Story by Andrew Kenney

Photos by Hart Van Denburg

Edited by Rachel Estabrook

Produced by Lauren Antonoff Hart