“Hey Anthony, how are you?” says a voice from 6,000 miles away.

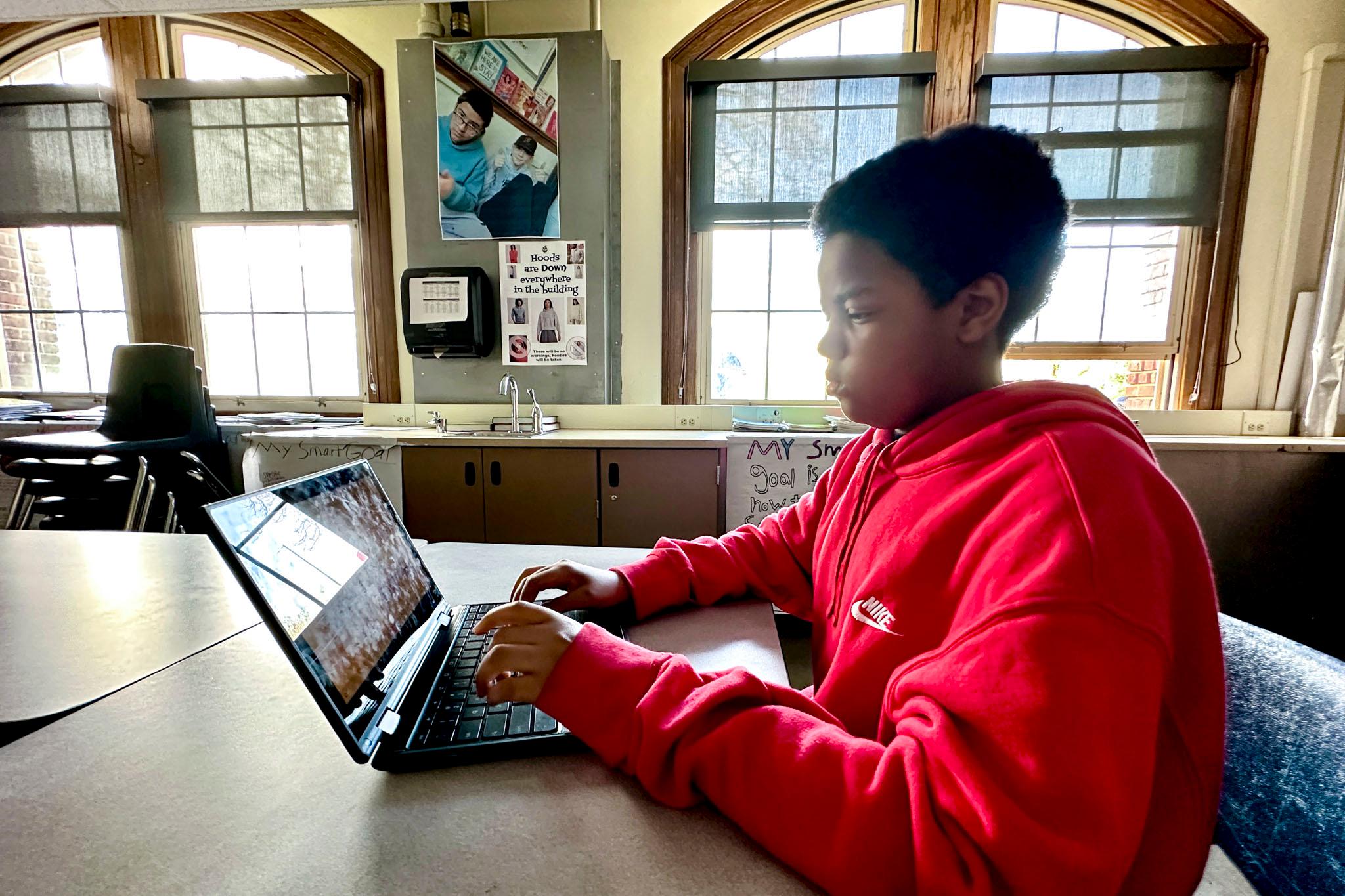

Twelve-year-old Anthony, in a classroom at Lake Middle School in Denver, is silent. His screen is muted. He types out “hi” in the chat to his math tutor.

“I don’t really like to talk during these,” he tells me.

But the sixth-grader decides to try something new because I’m next to him, recording.

“Hi mister,” he says shyly.

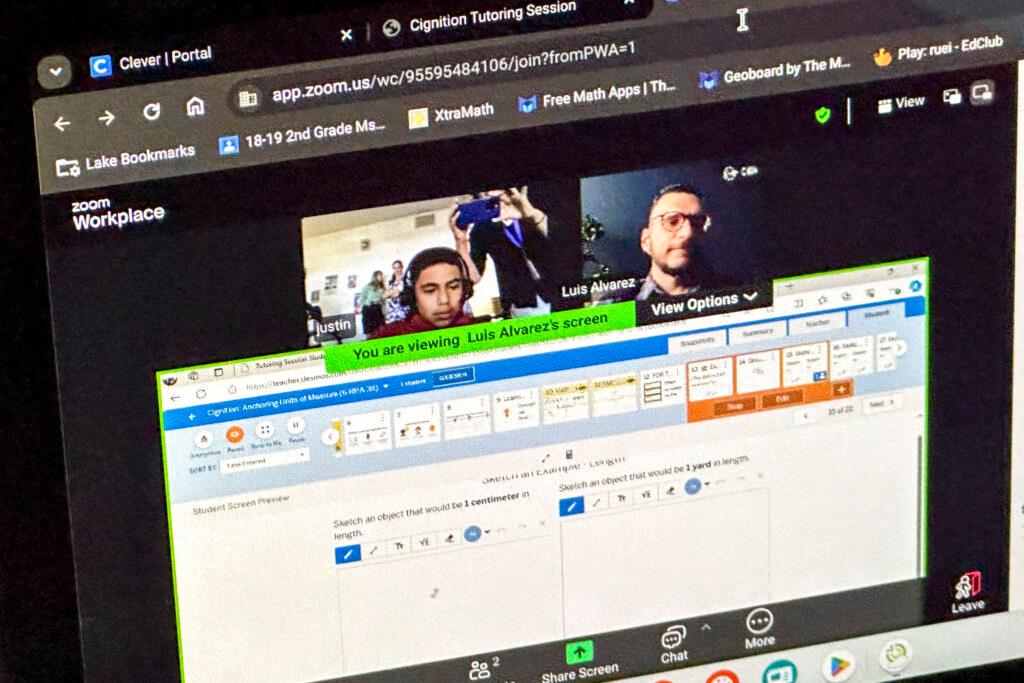

“Hey, how are you, Anthony?” replies Tomas Cobian, a tutor currently based in Argentina working for Cignition, a virtual tutoring company contracted through Denver Public Schools.

What Anthony is doing is called high-dosage tutoring. Kids are in small groups with similar needs. Anthony and his tutor immediately get down to business solving a problem about chocolate chips and biscotti.

The pandemic had a massive impact on students, especially in math

Less than a third of Colorado eighth-graders score proficiently in math. So, Colorado has invested heavily in high-impact tutoring programs — $20 million allocated in federal and state dollars since the pandemic. Colorado was also one of five states to get a $1 million grant from Accelerate, a nonprofit that aims to make high-dosage tutoring a feature of the American school day.

A large body of evidence shows tutoring is most effective when it happens during the school day, in small groups, using a high-quality curriculum, with experienced tutors, and frequently. One study showed students who complete high-dosage tutoring programs experience large gains in test scores, especially compared to other education interventions.

Some kids at Lake Middle School this year had more than two and a half hours of tutoring each week.

Math teacher Patrick Jiner said tutoring is indispensable. Class time isn’t enough, especially because math is cumulative and end-of-the-year tests reflect problems from the beginning of the school year.

“They may practice five, six problems on a specific standard … That's not enough, it's just not enough. It takes a lot of repetition and practice.”

Many Lake students say the biggest benefit is that tutors review what’s coming up in class so they’re ready.

“They teach the same thing that our teachers teach, so basically they’re teaching us that before we get to math class so we know how to do it,” Izzy, 12, said.

“I think the biggest challenge is figuring out what to multiply and what to divide,” said Janessa, 11, adding that tutoring has helped her go from a B to an A in math.

Lake Middle School needs the help. Last year about 11 percent of the school’s students were doing math on or above grade level. The school is in year four of the state’s accountability clock, a watchdog list. At year five, it could face more state oversight and intervention.

How many batches of chocolate chip biscotti can Franny make?

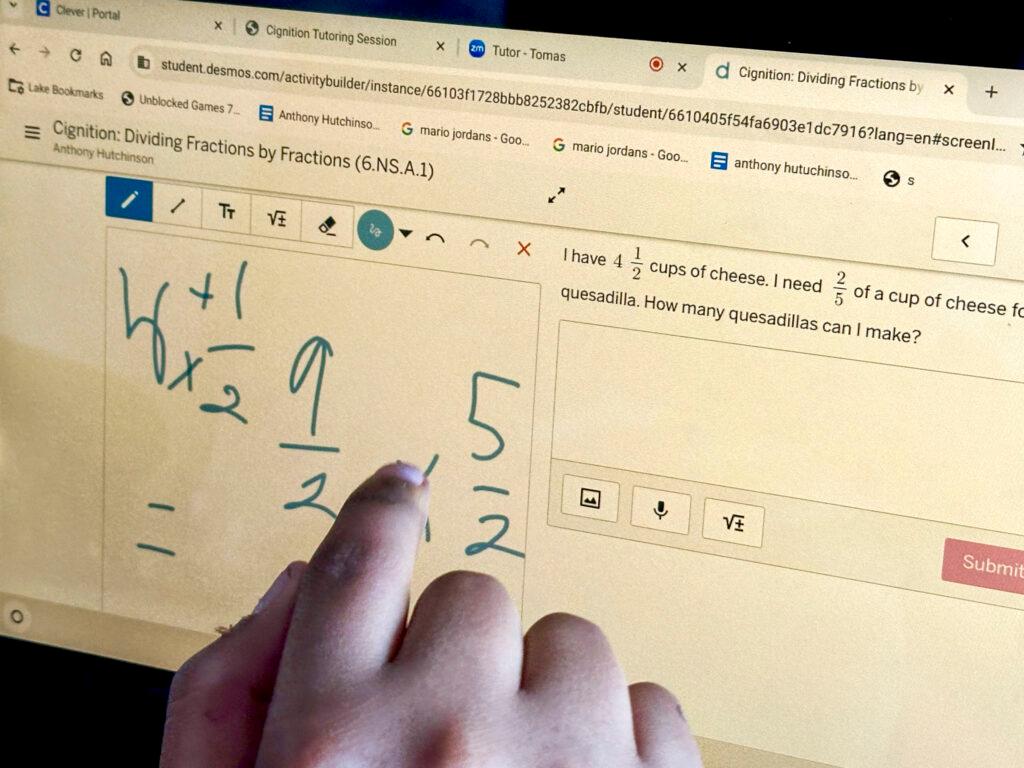

Tutor Cobian reads out the first question to Anthony: If it takes ¾ of a cup of chocolate chips for one batch of biscotti and Franny has 6 cups of chocolate chips, how many batches can Franny make?

“Hmmm,” said Anthony. He thinks about it for a long time. He’s stuck. Cobian breaks it down into smaller parts. He gives a hint: Look at the last row. You need ¾ of a cup.

“What operation do you think we could use to figure out the number of batches she can make? We know how many cups she has and we also know how many she needs for each batch?”

Cobian tries a different tack. He has Anthony imagine using simpler numbers: 6 cups of chocolate chips total but each batch needs 2 cups.

Anthony types some numbers into his calculator. More time passes. It finally clicks that “two can go into six three times” and that’s a division problem. Cobian explains that Anthony needs to use the same logic for that original question: 6 divided by ¾.

“How can we do that? What rule can we work on?”

“Keep. Change. Flip,” said Anthony, also known as the KCF rule.

Anthony starts doing the equation. But he momentarily forgets that to do a division problem, you need to flip that second fraction and multiply. Math is hard!

“Oh wait!” He suddenly remembers and then bangs out the answer.

They move onto problems about how much paint it takes to paint a room and how much cheese to make a quesadilla. Each time the tutor dissects Anthony’s thinking and gives him other strategies if he makes an error. Cobian is clear and encouraging and gently pushes Anthony to explain his reasoning. By the end of the class, Anthony seems more confident.

Anthony will meet with Cobian the next day.

What kind of results is Colorado seeing from high-dosage tutoring?

Just as federal COVID dollars for tutoring are ending, researchers say school district progress in recovering from the pandemic is only just beginning. High-dosage tutoring is showing positive, though incremental, change, according to Spencer Ellis with the Colorado Department of Education.

Last year, the program reached more than 5,300 students. About half of schools used existing staff as tutors. Another 18 percent contracted with a third party. In the latest round of state grants, all but two districts reported a positive impact on academic achievement. Some, but not all, reported a boost in math test scores.

“We couldn’t claim through this grant to have an impact on (state standardized test) scores overall but the little mini-analysis we’re seeing some indication that there could be some positive impact,” Ellis said. “We can’t recover this unfinished learning in the immediate future so this is an investment we wanted to make to start getting back on track.”

“It takes time to address deep, deep learning gaps,” said Katie McCullough with Kwigayagat Community Academy on Ute Mountain Ute tribal land. “When we're looking at 84 percent of our school is well below grade level. They come in at that level. We are making up for things way outside the realm of reading and math. That takes time and it takes trust."

Other observations: Teachers were overjoyed with the extra help. It took some students a while to engage with tutors. Middle school students need upbeat tutors who can relate to them. High school students aren't as excited about being pulled out of class for tutoring.

But there were other positive benefits: better attendance, engagement, and more practice at self-advocacy and problem-solving skills.

Still, Colorado schools are hampered by a shortage of tutors and chronic absenteeism. Nearly 40 percent of Lake’s students are chronically absent. And sometimes, even in Anthony’s tutoring group, the other two students stopped participating, cameras and microphones off, after a few minutes.

But overall, tutoring at Lake has had a significant impact

“This year on interim assessments, we've seen some of the highest growth but also students moving into like that green range, which are like being on grade-level range than we've seen in years past,” said Emily Felsenthal, an assistant principal.

On interim tests in May, the percentage of kids in the green range increased over last year’s state test scores: 36 percent higher for sixth graders, 20 percent for seventh graders and 36 percent for eighth graders.

Whether that boost will show up on the annual standardized tests won’t be known until August.

Though state grants for high-impact tutoring will continue for two more school years, Lake officials also don’t yet know whether they’ll have money for tutoring next year.

Sixth-grader Anthony is on a roll and hopes the support continues for his long-term future.

“I want to be like my Dad,” he said.

His father does carpentry and is studying to be a welder. Anthony said he uses math in his job.

“He has to cut the board exactly right or he has to start all over again. (He tells me) I should pay attention if I want to get a job like that … which I do.”