For U.S. Women’s Deaf National Team defender and Littleton native Mia White, coming home to play in front of friends and family was strange at first. Quickly, however, White found her footing.

“I grew up here. I remember this field when I was a child, so it's odd, but it's great. I'm really humbled to be back,” White said through an interpreter after a recent practice the team held in Colorado ahead of a friendly match against Australia. White had planned to play with her club in Finland until October — but when she got the call-up to the national team, she knew she couldn’t turn down the opportunity.

But, the USWDNT’s appearance in Colorado last week was not only a homecoming for her, it was also a homecoming for one of the world’s most dominant teams no one’s probably ever heard of.

The U.S. Women’s National Soccer Team was the main attraction at Dick’s Sporting Goods Park in Commerce City Saturday. The nation was eager to see the team — winner of four world cups — under new head coach Emma Hayes.

But, as part of a doubleheader, the USWDNT also took the pitch against Australia prior to the USWNT’s match against South Korea. It was the first time the deaf national team played on national television and on home soil.

What is the USWDNT and how long have they been around?

International organized deaf sports have been around since August 1924 with the creation of the Comité International des Sports des Sourds in Paris. In the United States, the American Athletic Union of the Deaf was formed in 1945 and later changed its name to the USA Deaf Sports Federation in 1997.

The first U.S. Men’s Deaf National Team for soccer was formed in 1965 and played to a 10th-place finish at the Deaf Olympics. The first Women’s Team was formed in 2005 to compete in the first Deaflympics in Melbourne, Australia. The team took the gold medal in its first international competition.

Both teams became part of the U.S Soccer Federation’s U.S. Extended National Teams. These included para-soccer (for those with visual impairments, those with hearing disabilities, those with cerebral palsy, and those who use wheelchairs), beach soccer, and futsal.

Since then, the USWDNT has a 38-0-1 record in all competitions and has won four Deaflympic gold medals and three Deaf Football World Championship titles with the most recent one coming in 2023.

To qualify to play for the USWDNT, players must have an average hearing loss of at least 55 decibels in their “best ear.” All players competing must remove hearing devices before matches. The referee uses a flag to visually start and stop play.

Former USWNT goalkeeper Amy Griffin is the head coach of the team. She was a member of the team when it won the 1991 Women’s World Cup. She was asked to lead the team because she has members of her family who are deaf. Griffin said her players are teaching her new things all the time.

“I'm not at all fluent, but the players make me feel appreciated for trying and I get better. Every camp I get better and hopefully I'll continue to improve,” Griffin said.

When coaching the team, Griffin says training is the biggest difference.

“When you have to coach and implement new ideas and bring in some finer details, it's different on how you would freeze practice, where we just get to yell, ‘freeze,’” Griffin said. “Normally, now we have to raise our hands and hopefully everyone has their head up and is paying attention and finding a variety of ways to communicate, whether it's verbal sign language or just moving bodies from point A to point B.”

Communication is key in any sport. For soccer, the most talkative position is the goalkeeper. They’re usually the ones barking orders to the players in front of them, especially during set pieces.

USWDNT goalkeeper Taegen Frandsen explains that most players in front of her know their roles.

“Most of the time they're not paying attention to me. But when I did get their attention, I signed to them,” Frandsen said. “And then on corners, I just make sure that they can see me and I can point to who I need to get marked up.”

The Journey

Players on the USDWNT grew up playing in clubs, high school, and college. Each journey with hearing loss and the sport is different for each player.

Littleton’s Mia White was born deaf. She doesn’t view her deafness as a disability.

“I don't really identify myself as having a disability. I was born deaf, I was born here. My family all sign, and so we use American Sign Language in the house,” said White through an interpreter. “We all have different words that we use and different perspectives. It's just the one that I use. The thing for me is that I can do everything, just not hear.”

White grew up playing regular club soccer. She attended the Rocky Mountain Deaf School in Jefferson County. The school has a small enrollment and doesn’t offer sports.

“There were only four people in my graduating class, so it was really a small class. I wanted to play high school soccer,” White said. “And so I joined a public school that was near my home. And so I played for Chatfield (Senior) High School. I played with them all four years throughout my high school program.”

She earned a Jefferson County All-League Honorable Mention selection and Colorado High School Activities Association All-State Academic honors playing for the Chatfield Chargers.

White said she was looking at schools and attended a Division I School ID Camp where players showcase their talents in front of college scouts. At first, she didn’t feel like she would fit in at a program being the only deaf player on the team. That’s when she discovered Division III Rochester Institute of Technology.

“I found out that Rochester has 1,200 students who are deaf. They have that soccer program, plus they have programs that I wanted to take as far as courses,” White said. “So I wanted to be a business major and they had that as an availability. I went to their camp, the coach saw how I played, we connected really well and they committed to having me there on the spot.”

In four years at RIT, White tallied 14 goals and 14 assists in 75 games and was named Liberty Conference Player of the Year. White has also made a career out of soccer, playing professionally for FC FTK in Finland.

Former CU player leaving her mark

Holly Hunter made her return to Colorado after being away for two years. The Temecula, California, native spent two years playing for CU-Boulder before transferring to Northern Arizona University after her sophomore year.

She said her situation was just no longer a good fit anymore in Boulder. But, she doesn’t have a bad word to say about the program.

Born deaf in both ears, Hunter uses a cochlear implant to communicate. A cochlear implant is different from a hearing aid. A hearing aid amplifies sounds so they can be detected by damaged ears. A cochlear implant bypasses the damaged portions of the ear and directly stimulates the auditory nerve.

Hunter credits her parents for ensuring her childhood was no different from others.

“I'm super grateful to my parents. They provided me a lot of support over the years, just getting me speech therapy and all of that stuff just so I could be successful,” Hunter said. “So, growing up I don't think it was much different than a hearing child. I would say I lived a pretty normal life and I'm just super excited for the opportunities that being deaf has provided.”

During most of her high school career, she played with the SoCal Blues ECNL and Legends FC due to development academy rules. She played one season for Great Oak High School before graduating.

Hunter chose CU-Boulder after being recruited by the top schools in the Pac-12 like UCLA, Stanford, and Cal.

“I toured all those different schools and I just felt that CU was the place to be. It had a beautiful campus, it had great academics, it had the Rocky Mountains in the background and I was just like, ‘This seems like a home for me,’” Hunter said.

In two years, she aided in five clean sheets and was a Pac-12 Academic Honor Roll selection.

After transferring to Northern Arizona, Hunter scored her first career goal against Sacramento State. Heading into her senior year, she has aspirations of becoming the first U.S. Deaf National player to crossover into the U.S. Women’s National Team.

Hunter’s recruitment into the USWDNT began when she was in the seventh grade. Current USWDNT head coach Griffin was the goalkeeper coach at the University of Washington. Hunter has been grateful for meeting Griffin ever since.

“I think we didn't have a lot of exposure because I didn't know about this team until I suddenly had a connection with college soccer and I just met Amy,” Hunter said. “That's how a lot of the girls began on this team. But nowadays, it's a lot different because there's so much more awareness. We're part of the extended national teams for U.S. soccer now, which is amazing.”

Historic match has an impact beyond the score

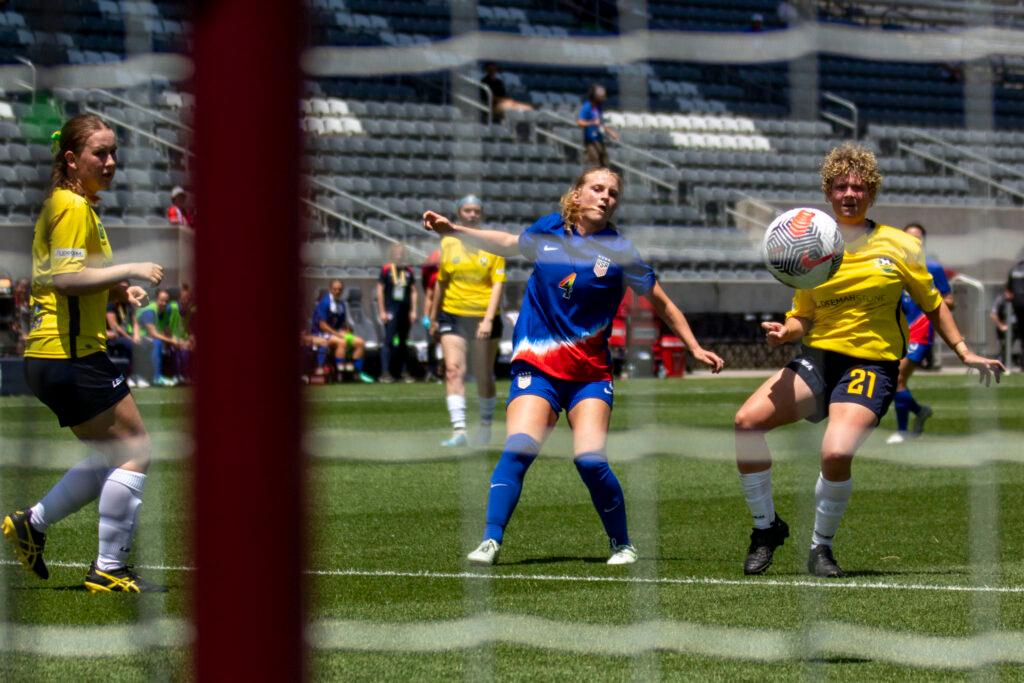

The USDWNT played Australia on home soil — for the first time — and in a televised broadcast — for the first time — at Dick’s Sporting Goods Park in Commerce City.

A small crowd watched USWDNT defeat the Australians 11-0 in an impressive performance. Emily Spreeman scored six goals to set an American single-game scoring record in an 11v11 match on the senior international level.

Nancy McAnlis never thought she would see that moment. Born and raised in Philadelphia, McAnlis, who is also deaf, is a lifelong soccer fan. She played on an all-hearing soccer team in high school.

“When I was in high school, I was a sweeper. I had my coach interpret, kind of indicate where the ball was through sign language, and then they would let me know to look back at the keeper,” said McAnlis through an interpreter. “So, the visual was there. Constantly, I could see the whole field.

She would go on to play for Gallaudet University, a deaf university in Washington, D.C. McAnlis described her experience with the Bison — Gallaudet’s mascot — as phenomenal.

“Everyone on the team knew sign language. It was effortless to know where the ball is, where the keeper is. It was again, effortless,” McAnlis said. “Now, really the point is that soccer is a visual game. You have to know where the ball is. So really, as far as when it comes down to actual communication, it's minimal. You could point and then you could gesture, and it's very effective that way.”

McAnlis is an assistant principal at the Rocky Mountain School for the Deaf, the same school her former student White attended. She said she hopes more students from the school make their way to the USWDNT.

Graham Geteer and Gia McCarthy participated in pre-match ceremonies as mascots for the USWDNT. In soccer, mascots escort teams onto the pitch hand-in-hand with players.

The nine-year-old Geteer currently plays striker for his team. His dad, John, knew how important it was for his son to watch the match.

“They're a great team. They're up six (to) zero, they're just insanely good and he doesn't see a lot of that,” John said at halftime. “He plays a lot of sports, but they're with hearing children. So, he gets to see his community do great today, which is awesome.”

McCarthy attended the match with her family to learn more about soccer. Through an interpreter, she said she’s more excited to learn more about the sport.

“I play on other sports teams and so I learned about them and I want to learn how to play defense and run better. And so I'm here to watch them,” McCarthy said.

After the match, preparations are now underway for the 2025 Deaflympics in Tokyo. For White, the team has the momentum to win a fifth gold medal.

“We're one step further than we were. Our goal is to win the Deaf Olympics in Tokyo, and we're one step closer to there and it starts here. It starts today. This is day one and now that's out of the way and we go from there,” White said.