When money’s tight, some people sell their plasma. William Jacques, who visited CSL Plasma in Aurora recently, has donated plasma twice a week for about 12 years. He brings in around $460 a month, which Jacques likened to a part-time job.

“It goes to bills. Gas, insurance, tires, whatever,” he said.

Jacques added that while the money’s good, he’s mostly happy to be able to make a difference for people who are sick.

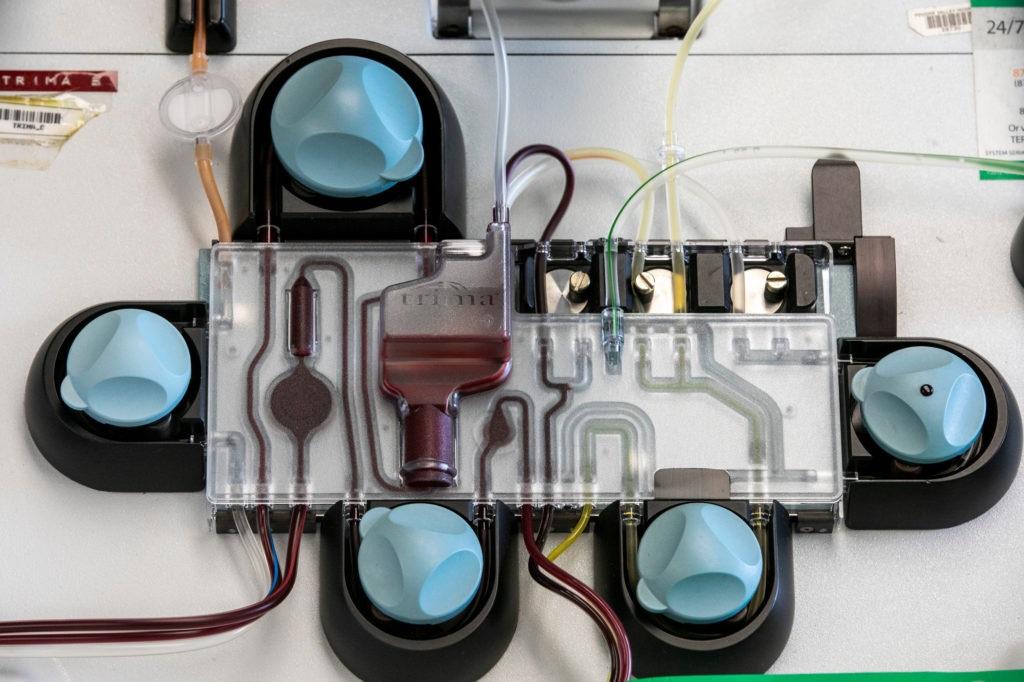

Human plasma, which comprises the largest part of whole blood, is a pale yellow liquid that gets extracted – often at commercial plasma centers – and is used in a variety of treatments. Pharmaceutical companies use plasma to make prescription drugs that treat illnesses ranging from auto-immune disorders to genetic diseases like hemophilia.

Emily Gallagher of the University of Colorado Boulder co-authored a study with researchers at Washington University in St. Louis about people who sell plasma. Researchers surveyed people in 2018 and 2019 and found most plasma donors tend to be low-income and younger.

“They're also much more likely to identify as male and also to identify as African-American. They tend to have children,” Gallagher said. “They're often unemployed or underemployed and tend to make an income of less than $20,000 per year.”

Gallagher said many donors have little in savings and poor credit scores. The centers themselves tend to be located in densely populated areas that are home to low and middle-income residents.

Plasma centers pay an average of about $50 per visit but offer as much as $200 per visit when major shortages exist.

Ross Davis, who visited CSL Plasma on the same day as William Jacques, said he goes to the center when he has a big bill to pay or when business at his food trailer is slow.

“If you have a bad day, well then you end up doing something like this to substitute the money that you didn't make,” Davis said.

Davis got $100 the first time he donated plasma because centers often offer a first-time “bonus.” On this day, he took home $65.

Gallagher notes, there may be additional financial benefits for plasma donors. Researchers found that when a plasma center opened in a neighborhood, young people were less likely to take out payday loans, which charge extremely high interest rates. In addition, they found the opening of a new plasma center leads to an increase in foot traffic at the local grocery store, which could mean people are using the money to buy food.

“These are very similar effects to what other researchers have found when a local area raises the minimum wage by $1,” Gallagher said. “So you can think of a plasma center opening in a neighborhood as kind of analogous to a $1 increase in the local minimum wage.”

Colorado is home to just under 30 plasma centers, mostly in metro Denver, and those numbers appear to be growing nationally.

“Since 2014, the number of plasma centers across the US has more than doubled. There's now over a thousand plasma centers spread across the country,” said Gallagher.

The World Health Organization advises countries not to allow for compensated plasma donation because the group is concerned about the health effects of frequent donations, however, researchers note that the existing medical research is inconclusive.

“There are anecdotal reports about high-frequency donors blacking out, experiencing fatigue and being more susceptible to infections,” Gallagher said. “But the existing medical research really doesn't tell us much.”

Gallagher said that while many of those surveyed had only donated once in the last six months, about 30 percent did so 10 times and about 10 percent donated 40 times.

U.S. regulatory limits allow donors to give plasma up to twice a week or 104 times a year while many other countries have stricter limits on donation frequency and compensation.

Gallagher said the moral questions that come with plasma donation are complex.

“There’s this potential exploitation of people selling the plasma (combined) with the fact that plasma-derived medications are incredibly important to people,” Gallagher said.

People also donate plasma at non-profit centers like Vitalant and the Red Cross without getting compensation.