Sure he has won the biggest prizes in science fiction– the Nebula and the Hugo awards. But Paolo Bacigalupi found himself bereft of inspiration. Penning apocalyptic climate fiction, like 2016’s The Water Knife, had taken its toll.

“When you’re starting to write again, it’s like sticking your finger in a light socket. It is sort of painful and damaging,” he said.

The Paonia-based author knew it was time for a change. Then the invitation came.

A wine-importer friend who knew Bacigalupi’s penchant for languages (he’d studied Chinese in college) invited him to Bologna for a crash course in Italian.

The answer was yes.

“I was down in a hole at this point. And so you really value friends who reach down and drag you up.”

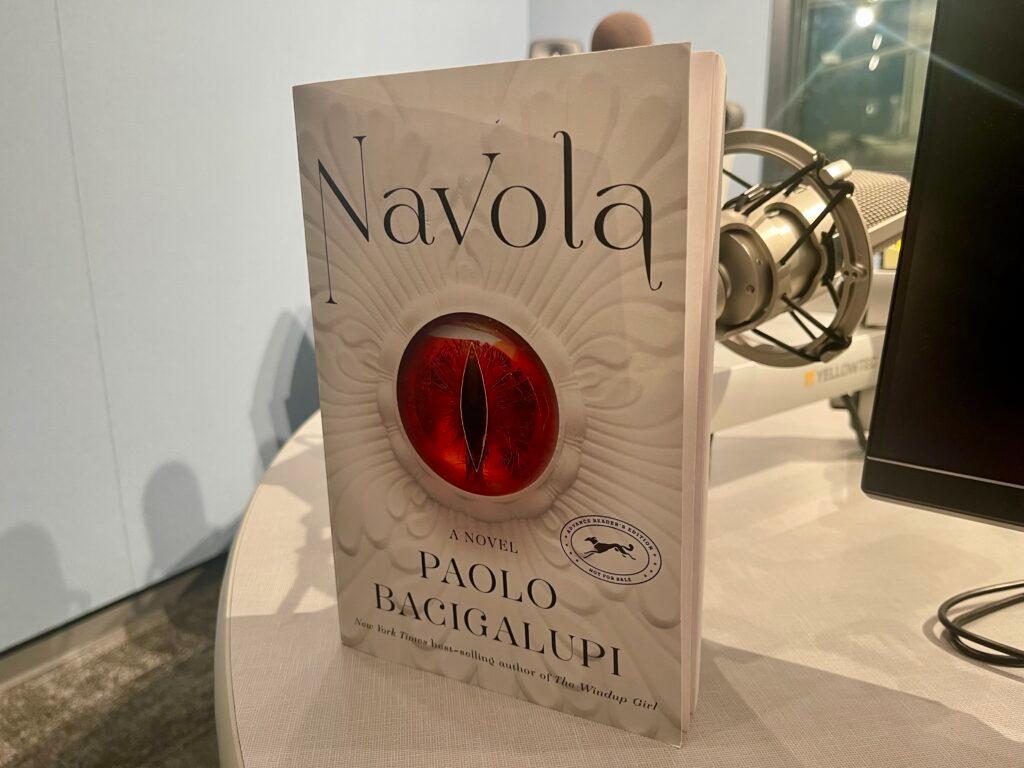

The real-life Bolognese setting inspired Bacigalupi’s new fantasy novel, “Navola.” It takes place in a city-state reminiscent of Florence or Venice during The Renaissance.

His protagonist, Davico di Regulai, is the son of an uber-wealthy merchant and banker. The boy has big shoes to fill, but very different feet, as it were. Armed with a preserved dragon eye that possesses magical powers, Davico struggles to be the man his father and community expect him to be.

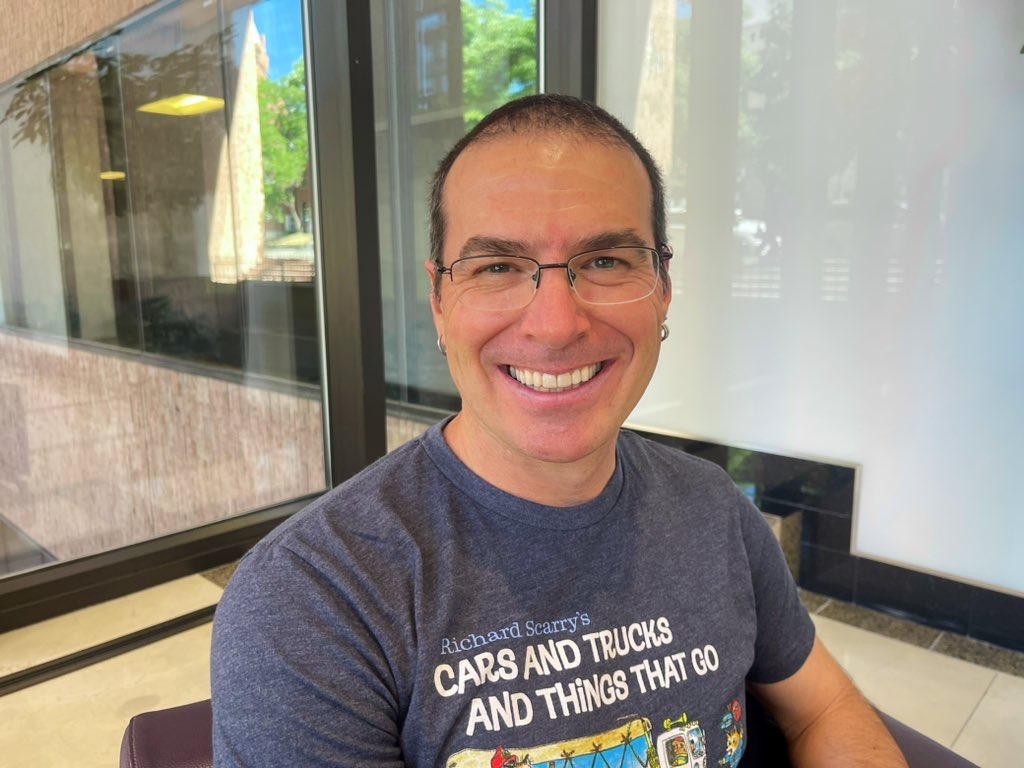

Paolo Bacigalupi spoke with Colorado Matters Senior Host Ryan Warner about Davico’s journey and his own.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ryan Warner: How did you know it was time for something different?

Paolo Bacigalupi: Well, when you keep trying to write things and you keep failing to actually finish them, or even when you're starting to try to write, it's like sticking your finger in a light socket. It is sort of painful and damaging, you think ‘maybe I should do something different.’

Warner: And that's how it started to feel in the climate change space?

Bacigalupi: Yeah. A lot of what I was doing, the news was bad, and then the stories that you're trying to tell are extrapolations on the present day, and those are all terrifying. Then you find you're in this space where your creative world and your regular life are all smashed together, and they're all really negative and they're all full of terrors, and it's not a sustainable space to be. If you spend all of your imaginative time in anxiety, then yeah, it takes a toll and eventually you just break down entirely.

Warner: And if the writer isn't enjoying it, how possibly could the reader?

Bacigalupi: Yeah. I think that a healthy writer finds pleasure in their work. I think there are unhealthy ways to go about doing good work, as well. The outcome can be good, but the damage internally is bad for the writer.

Warner: This isn't just about pleasing the audience. This is about making sure you have your mental health.

Bacigalupi: Right, exactly. If you're skillful enough, you can execute almost regardless of your state of mind on some level. But the toll, at least for me, was huge. So I ended up feeling like I needed to reset and to find some sort of pleasure space or enjoyment or sense of fun or sense of play in order to do any more creative work at all.

Warner: We meet your protagonist Davico when he's a boy. He's the son of a wealthy merchant. Who are the di Regulai?

Bacigalupi: The di Regulai family are merchant bankers. And so over a course of several different generations, they've accumulated an extraordinary amount of wealth. They are so powerful and they're so wealthy, that in their bank and within their family, they're probably richer than many nations around them, certainly many city-states around them. And so they are the lenders of choice – whether you're a king or whether you’re a merchant sailing across the world, you're going to come to the di Regulai for funding. They deal, as Davico's father, Devonaci di Regulai says, less in goods and more in promises. And he never fails to collect.

Warner: ‘Navola,’ the title of your book, refers to the city-state where the di Regulai live and prosper. How do you picture this place and when exactly is this? It's certainly a time of dragons and swords and poisons.

Bacigalupi: I've modeled it broadly on Renaissance Florence, Renaissance Venice, that period. Late 1400s, early 1500s. That's the model that I'm overlaying my own magical cityscape atop. And so you can imagine the cathedrals. You can see the giant domes. You can see the tall defensive towers that the most powerful families of Navola have erected for warfare between one another when they have their blood feuds. And this is a place of broad plazas where a lot of the life of the city is happening. And then there's all the narrow alleyways where all of the dark back-stabbings and knifings and drinking games happen.

Warner: You get to invent a lot. Language and places and people and faiths. And it makes me wonder how you channeled your imagination as a kid.

Bacigalupi: I played a lot of Dungeons and Dragons. There was a lot of role-playing gaming going on, and that was actually where I learned my first storytelling skills, was being the game master and guiding the players through an experience from the beginning all the way through to the big shocks and twists and turns of the story, as they're living through it. You start to develop some of those tools. I didn't realize that I was developing storytelling tools or what I was exactly doing, but that was entirely the space that I was working in.

Warner: Someone is going to look at the last name Bacigalupi, and wonder to what extent your own Italian influences or exposure might be making it into this book. Am I making too much of a leap there?

Bacigalupi: No. It’s an odd thing. I have this name Paolo Bacigalupi, which sounds so very Italian! The truth is, I think I'm 1/32 Italian. I am unbelievably watered-down. But I ended up going to Italy with a friend of mine and studying Italian with him. He was a wine importer and he wanted to learn Italian. My background is actually that I studied Chinese. I've always felt that if you want to learn a language, you really have to immerse, you have to be studying, but also in all of the rest of your time, you have to only be speaking your target language. And so at one point he was like, ‘Yeah, I need to learn better Italian so I can do business over there. I think I'm going to go over and just speak Italian, nothing else. You want to tag along?’ And this was during my period of deep creative burnout. And I was like, ‘Sure, why not drag me along?’ And he organized pretty much everything. All I had to do was buy the plane ticket and show up.

Warner: Amazing offer.

Bacigalupi: Yeah, and I was down in a hole at this point. I had lost all energy for any creative work at that point. And so you really value friends who reach down and drag you up. And it did. It kind of pulled me out of a funk. You're in Italy and studying every day. And he and I were only speaking Italian, which is wearing a straight jacket because there's only so much you can communicate in your pigeon Italian or whatever. And yet we kept going and our Italian got better.

We were living in Bologna. And then all of the details of Bologna come to life around you, and you don't even really think of yourself as doing research, but you're becoming more and more and more embedded in a place and you're seeing all sorts of details that you're incorporating.

And so then as I started working more and more seriously on this story, I started having a lot of things at my fingertips.

Warner: Perhaps the most powerful symbol in this new novel is that of the eye. How did that come to you?

Bacigalupi: The dragon eye was the very first thing that launched the story, and the first line of the book has survived intact right from the very beginning. And that was, ‘My father kept a dragon eye upon his desk.’

This was during that period when I was down in the hole trying to figure out how to be creative again. And I was basically trying to write anything, 500 words a day of anything. And I would write 500 words and then I would just walk away. It could be good, it could be bad. But that line, ‘My father kept a dragon eye upon his desk.’ That had power to me, and that opened up doors to me and that eye, that dragon eye… then you're starting to ask questions, ‘What does this dragon eye look like?’ ‘Where did it come from?’ ‘Who's the man who has a dragon eye on his desk?’ ‘What does he do with it?’ ‘Who is the boy looking at his father with this dragon eye, and what is the boy like?’ And each of those opens up doors in the story, and that became a very lively space for me to play in.

Warner: How much did you think about your own son as you wrote about this boy who becomes a powerful young man, who’s then put in some horrendous predicaments?

Bacigalupi: It's interesting, fathers and sons, if you're a good father, you're helping your child become the person that they're trying to become. You're trying to understand them well enough so that they can achieve the fullest version of whatever they themselves are and are coming to be. And that's not you saying, ‘I think you should be an artist, or I think you should be an engineer.’ It's trying to observe this person and open the doors for them where you can, lift them up, encourage them, but fundamentally observe what is their deep desire and how you support that and help them develop the strength to pursue that thing– the resilience to pursue the things that they want to do and the person that they want to become.

Warner: Does Davico have that in his father?

Bacigalupi: No. And this was interesting to me. Looking at Davico and Devonaci, Devonaci di Regulai has a very important role. He's master of politics. He's master of trade. He's a central figure holding a certain kind of political stability together. And Davico is expected to inherit and take on those roles. So this is a family that, for all of its wealth, is also constrained. It has real enemies. It has real responsibilities. And Davico is not just expected to, but the family needs him to assume those roles, even if that role might not fit his natural character. Davico is kind, and he's very trusting and he's very open. His father is shrewd and his father is calculating, and there's a mismatch there. And it's not like Devonaci is a bad father. Davico's perception is that he's well-loved by his father, and yet the role that Davico has to take on is huge and serious, and it's serious that he's not well-suited for it.

Warner: Do you imagine that Navola is where you will set 10 more books?

Bacigalupi: If people would let me do that, I very much might. I love living in this space. I love creating stories. I actually just wrote a short story for a magazine set in Navola, but about a totally different character. I wrote up a short story about this itinerant artist who's been running around and creating forgeries of ancient art, and he's hilarious. He's just a whole other character. And you're like, ‘Oh, yeah, I could follow him around!’ There's a million people and there's a million different layers to the city, as well, that I would like to explore, and so it's rich.