The University of Colorado is the latest mainstream university to create a dedicated center for the study of psychedelic drugs, and its leaders are already dreaming up new experiments.

The CU Denver Center for Psychedelic Research will be based in university offices in downtown Denver. The center is starting small, but its creation signals the university is committed to researching the potential benefits and effects of psychedelics as a medicine, as well as the legal and social aspects of Colorado’s emerging psychedelic industry.

But what exactly will they study?

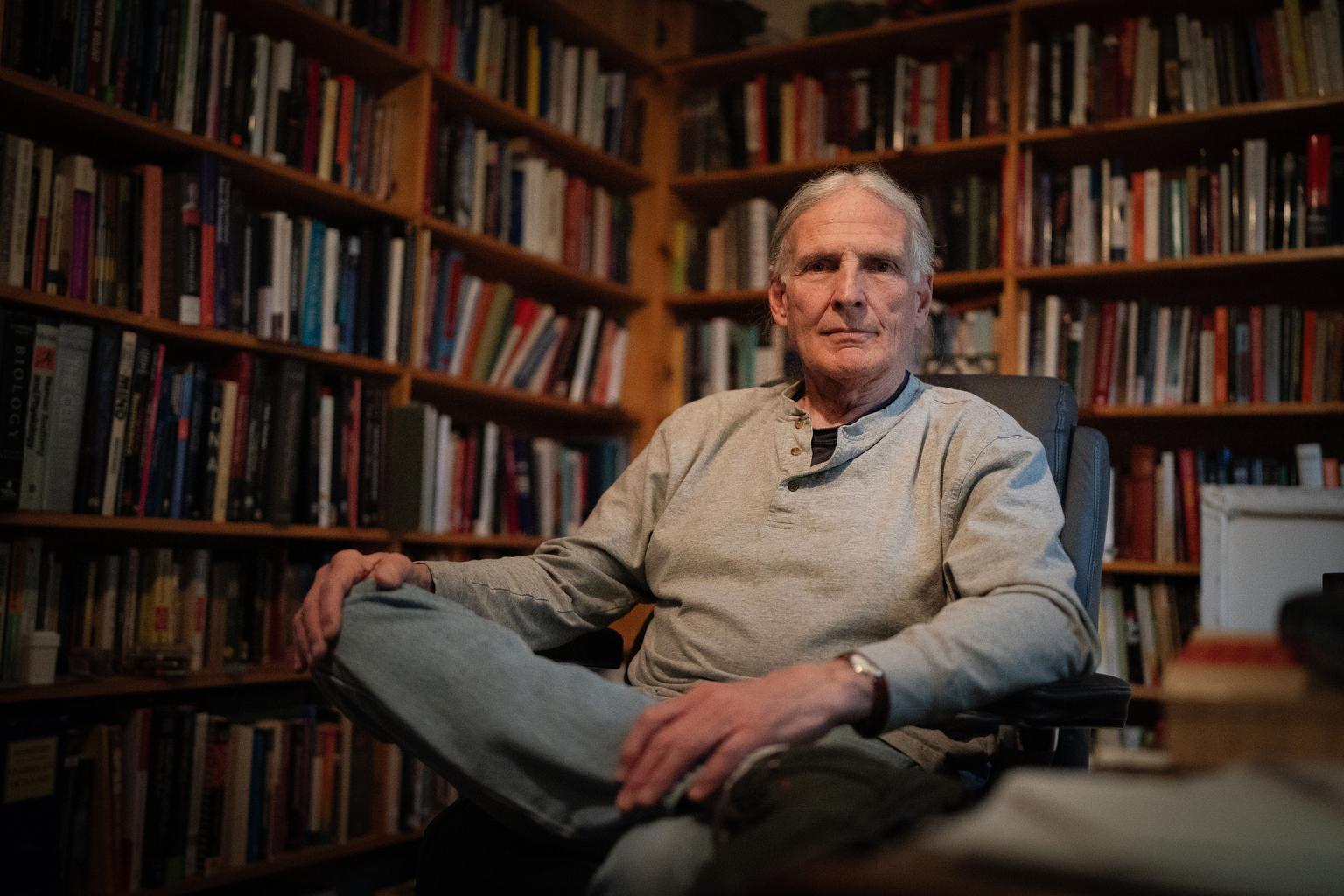

In an interview, neuroscientist and center director Jim Grigsby shared some of his early ideas and plans.

MDMA for dogs

Researchers have been asking if MDMA, a drug sometimes known as ecstasy or Molly, could help people with post-traumatic stress disorder. Grigsby suspects that it could be beneficial for traumatized dogs, too.

Previously, Grigsby was part of a 2019 study on the effect of MDMA on rats. The study tested whether MDMA could help rats unlearn their fear of a setting where they had experienced a mild shock.

“Our idea was that the memory of the fear itself can be reduced or eliminated,” Grigsby said. That experiment showed further support for the effectiveness of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, he said. The study showed that MDMA might disrupt the “reconsolidation” of traumatic memories — the process by which they are accessed and then stored again in the brain.

“Every time a memory comes into awareness, it becomes, in a way, fragile, and susceptible to being changed. You can actually change the neural network [that stores the memory],,” Grigsby said. In short, MDMA and other psychedelics may affect the memory rewriting process in a way that edits or eliminates the traumatic memory itself.

Grigsby’s plan for an experiment with dogs would build on that research, but with a different setup — instead of intentionally creating a fear or trauma, it would focus on helping dogs who were previously neglected or abused.

“I’m working with a group of local veterinarians who are pretty interested in this,” Grigsby said. The idea is to study MDMA’s therapeutic potential for both humans and canines. They’ve found a source fo the study drug and now are looking for funding.

MDMA is a “non-classic” psychedelic. Instead of instilling “mystical” experiences, it produces a mellower effect during which people tend to feel more empathic, more open to bonding with others, and better able to process emotional or traumatic memories, according to the UC Berkeley Center for the Science of Psychedelics

Potential medical effects of psilocybin

Grigsby is interested in the possibility that psychedelics could boost neurogenesis, which is the growth of neurons. Until fairly recently, neurogenesis was thought to be impossible, but researchers have found that it does occur in parts of the brain, and the phenomenon may also get a boost from certain psychedelic substances.

“With LSD, for example, it's estimated that maybe for three to four weeks after a session, there's change in the nervous system that's occurring,” he said. Grigsby’s team is talking with researchers at a local rehabilitation hospital about a potential study of psychedelics as medicine for recovery from strokes or traumatic brain injuries.

Separately, Grigsby also is interested in the possibility that psychedelics could reduce inflammation in the body. That might happen indirectly, if a therapeutic application helps to reduce stress and improve a person’s general health. It also appears there may be a direct link between psychedelics and the reduction of inflammation. Finding a way to reduce inflammation could help treat autoimmune disorders and certain neurologic.

Psilocybin for a better death

Grigsby is already co-leading a study of whether therapy and a big dose of psilocybin (a key compound in psychedelic mushrooms) could help people confront their cancer diagnosis. It’s funded by about $3 million in federal grants, but Grigsby says that the new center will try to raise potentially millions more to support the study over the next few years.

“We might be able to get it done a bit more efficiently, and maybe somewhat more rapidly if we had more money,” he said. Currently, the study is relying on a fair amount of volunteer labor from therapists.

Beyond medicine

The new center also will be part of Colorado's broader embrace of psychedelics. Voters in 2022 passed Proposition 122, which removed many criminal prohibitions on psilocybin and certain other drugs. The state is now creating rules for “healing centers” that will legally offer psilocybin as a therapy.

The center will study the application of the new law, the ethical and public health ramifications of the changes, and the question of how insurance might cover new treatments. The center also is expected to develop a training curriculum for people who want to work in the emerging psychedelic therapy industry.

The new center is just getting started. Grigsby is working now to raise money and hire a couple staffers.

“As we are able to raise some funding, in order to be able to do this properly, the center is going to grow,” he said. At present, there are several people who are affiliated with the center but who aren’t paid by it. Grigsby expects he’ll soon hire one or two more to help with administration and operations so that he can focus on research grant proposals.

“It's really just in the beginning stages. But I'd really like to see it play a pretty significant role, nationally,” he said.

The biggest challenge?

But among all these interesting ideas, the researchers know they’ll face a profound scientific hurdle.

The gold standard of science is the double-blind study, where patients don’t know if they’re receiving a placebo or the actual drug that is being tested. This technique is meant to reduce bias from participants and researchers, and to combat the placebo effect.

Unfortunately for psychedelics researchers, it’s very hard to successfully use a placebo in their trials. Patients often know that psychedelics have powerful and distinctive effects — making it easy for people to guess whether or not they’ve received the real thing.

“They produce extraordinary states of consciousness, and it becomes readily apparent what's going on,” Grigsby explained.

Those kinds of concerns popped up, among other criticisms, when an FDA advisory panel recently voted against the use of MDMA to treat PTSD.

This and other research barriers mean that “psychedelic science is facing serious challenges that threaten the validity of core findings and raise doubt regarding clinical efficacy and safety,” warned a recent study in Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology.

Grigsby and his colleagues are well aware of those concerns and are working to bulletproof their research — and they’re hoping to explore specific scientific techniques that could counter issues with blind trials.

For Grigsby, the launch of the center is a career capstone. As CPR News explained in a recent audio documentary, he initially wanted to study psychedelics back in the 1970s, but was forced to wait for decades as research opportunities disappeared and psychedelics were all but ignored by the mainstream.

“We are optimistic … that we will be able to raise sufficient money that we can conduct some well-designed clinical trials that would answer a lot of questions,” he said.