We all know about gold and silver being early economic engines in Colorado. But what about prom corsages and bridal bouquets?

The dianthus caryophyllus, the ruffled, multi-petalled flower bloomed a multi-million-dollar industry and catapulted Colorado into the “Carnation Capital of the World” for several decades.

Then poof. Carnations disappeared. Why?

That was Carol Heepke’s question, so she asked CPR’s Colorado Wonders about it. And it’s a good time to answer her: Next weekend is the Wheat Ridge Carnation Festival.

Colorado’s carnation story is a fascinating one that includes free shipments of the flowers to Mamie Eisenhower, advertisements in Vogue magazine, and cutting-edge research from a local university that later ironically helped speed up the demise of the Colorado carnation.

Why was Colorado a prime location for growing carnations?

The climate was perfect. Many hours of direct, high-altitude sunlight, warm days and cool nights. An irrigation ditch built in the 1880s brought water from Platte River Canyon into Denver. That allowed greenhouses to be built and the floral industry grew rapidly. The blooms were delivered by horse-drawn carriages warmed by charcoal heaters in the winter to keep them from freezing, according to a Colorado State University paper on the industry.

Those were the early years. Things really took off in 1921, when a shell-pink flower called the “Denver” won a bronze medal at the National Flower Show. One hundred of the “Denver” carnations were sent to the White House for Warren Harding’s inauguration. The president-elect wore a Colorado carnation in his lapel.

Denver’s central location with a well-developed train system made it easy to transport carnations anywhere in North America. By 1929, Colorado flowers brought in more income than gold. Beautiful carnation bouquets decorated festivities nationwide. First Lady Mamie Eisenhower wrote a letter to the Colorado Flower Growers Association thanking them for regular shipments of carnations sent to her eight years in the White House.

California had more production than Colorado but the Mile High state was considered the “Carnation Capital” of the world because its carnations were routinely judged as the finest in the world, trademarked with a gold seal to indicate quality and perfection.

In the greenhouse

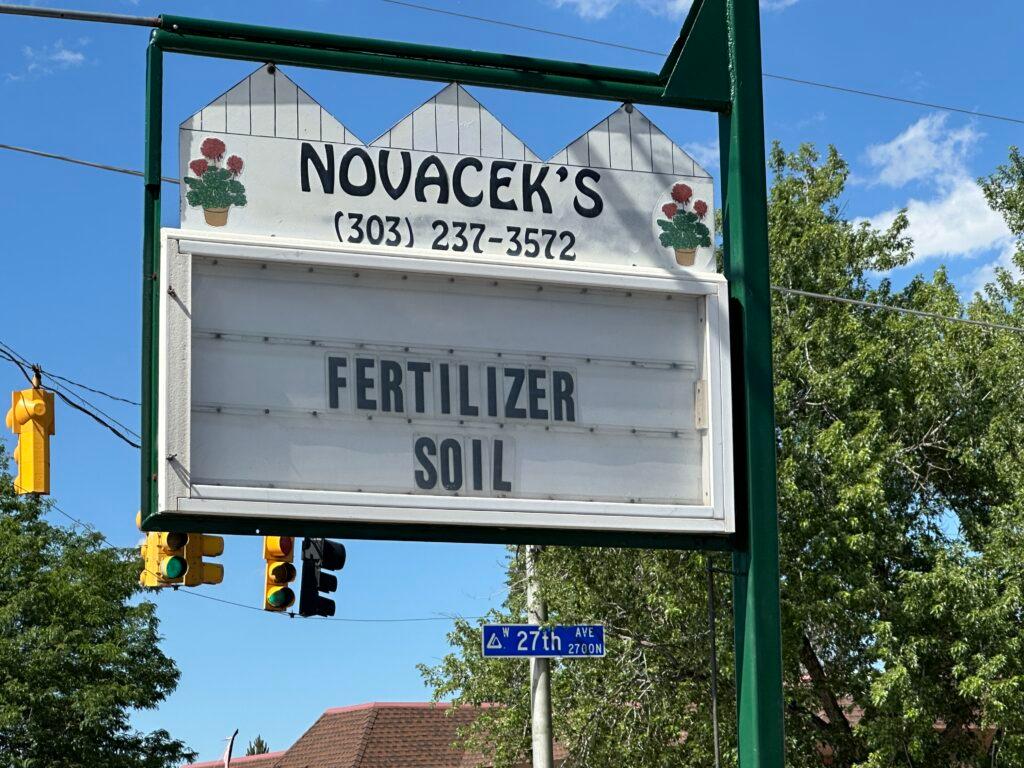

In Colorado, there were a number of families who dominated the carnation industry – from the Amatos to the Yoshiharas. But there were also dozens of mom-and-pop operations especially centered in Golden, Arvada and Wheat Ridge. In 1949, Joe and Lucille Novacek built the family’s first greenhouse in Golden. They grew about 38,000 square feet of carnations at the height of Colorado’s boom.

As a teenager each morning, Jerol Novacek, one of Joe and Lucille’s sons, would walk the benches of carnations, cutting the open blossoms. Then they’d be graded into categories like “fancies” (those with long stems around 26 inches) “standards” and “shorts” before being shipped off to wholesalers.

What Novacek loved about growing carnations was that there was always something new to learn about how to boost quality and quantity. CSU was instrumental in the industry’s expansion through teaching and research in monthly bulletins.

“They had different subjects that they would talk about, whether it was fertilizer, whether it was soil, whether it was greenhouse coverings, heat systems, carnation varieties, there was all kinds of information,” said Novacek, 82.

The bulletin became the major source of carnation research information throughout the world.

Walt Pettit, 83, who sits on the board of the Wheat Ridge Carnation Festival, also has fond memories of the days when carnations were king. His carpenter father built many of the refrigeration lockers at the big wholesalers.

“I loved those days of going down to the Denver wholesale market,” he said. “I loved the fragrance when you walked in the door, all these flowers smelled so good.”

As a teenager, he too worked in a greenhouse, cutting buds below the bloom for 70 cents an hour.

Nationwide, culturally, carnations were big. White carnations became associated with Mother’s Day, and later red ones with Father’s Day as noted in this 1913-14 Book of Holidays used in Colorado schools.

The Colorado Floral Growers Association funded research and promoted the state's carnations aggressively such as placing ads of fashionably dressed women holding carnations in Vogue magazine.

Once a process to dye the flowers was discovered, colorful carnations were everywhere, from the green one a naval officer placed in President Dwight Eisenhower’s lapel for St. Patrick’s Day to the “peppermint” carnations Mamie Eisenhower popularized.

At dances and other events, Walt Pettit said the trend was carnations for men’s boutonnières and women’s corsages.

“Carnations, always carnations,” he said.

Pettit remembers the day when he bucked that trend. He wanted to impress a special girl in high school so he asked for a corsage with an orchid – imagine! — instead of a carnation. The florist said it would cost him. It didn’t matter.

“Carol was actually the hit of the dance because she had this beautiful orchid corsage rather than a carnation,” he laughed. “Was I a traitor to the carnation business? I don't consider myself a traitor. I just had a deep affection for a special corsage for my girlfriend.”

It worked. He and Carol got married.

A 5-foot-tall world record

By the mid-1960s, carnations had grown into a $10 million business, making their value exceed the combined value of all fruit crops raised in Colorado.

Jerol Novacek loved growing carnations. One of his fondest memories is when the family created the world’s largest bouquet ever sold by a florist at the Wheat Ridge Carnation Festival. It was approximately 5 feet in diameter and 5 feet tall and weighed 75 pounds.

He said Colorado growers were a tight, close-knit community with a lot of camaraderie. They toured each other’s facilities to learn new techniques. They hosted competitions.

“It was a very fun and very exciting time during those late ’50s and early ’60s before South America started coming into the picture,” he said.

A Colorado connection to the Colorado carnation’s downfall

South America. Colombian carnation imports started flooding the market. Labor costs were cheaper there. Refrigerated airlines could transport boxes to the U.S. within hours. There were also other factors. Colombia had favorable trade agreements with the U.S., which was in the business of encouraging stable foreign economies in the 1960s-70s.

In 1966, the U.S. government sent agricultural experts, including four from Colorado State University, on a mission to Colombia to share knowledge. CSU also sponsored a dozen South Americans to study agricultural techniques in the U.S. CSU graduate student David Cheever was on one of the missions. His 1967 thesis on how Colombia could be a world cut-flower exporter was the catalyst for what would become the country’s $2 billion flower industry — a revolution that would eventually lead to the decimation of Colorado carnations.

Back in Colorado, carnation growers were panicking

“We could see the income was going down,” said Novacek. “It was getting harder to move your product and get a decent price for it.”

The fun and excitement of the 1950s and 60s quickly shifted.

“It was just survive … how do you survive?” said Novacek quietly, reflecting back.

In 1974, Colorado was still the No. 1 producer of carnations worldwide. But soon, the number of growers began shrinking precipitously. Novacek’s father, Joe, decided to retire at 62 to see if Jerol could make a go of it. Wholesalers began going bankrupt. Big greenhouses, amassing debts, started shifting production into roses and bedding plants. Older growers sold their lands. There were fewer wholesalers to buy Novacek’s carnations.

“It just kept tightening up and tightening up,” he said.

Novacek hung on. He added selling carnations retail and implementing techniques to make the carnations grow faster. But the hammer kept coming down.

In 1991, President George Bush suspended import duties on Colombian flowers. Novacek said consumer tastes were also changing — away from carnations toward arias, freesias, big tulips and lilies.

Sitting in a straw hat in the large greenhouse in Golden that his dad built, Novacek remembers the end clearly. He was bringing his carnations into the single business who was still taking his flowers.

“You walk in and you see the South American boxes on the floor and they say ‘I don’t need you anymore,’” he said. “I came home and told the wife, that was it. We threw out the rest of those carnations that year and we turned the whole place into bedding plants that following year. We were the last carnation grower in the state of Colorado.”

That was about 2008. It was hard and emotional for the family, especially Novacek’s mother, Lucille, who had devoted her life to that one beautiful flower, the carnation. At 82, Novacek still sells bedding plants from his greenhouse front door in Golden via word of mouth.

It’s hard too, for Walt Pettit to not miss the carnation era. But Pettit said even though it’s just memories now, he still encourages people to put some carnations on their float or wear a carnation at next weekend’s free Wheatridge Carnation Festival.

And if you’d like to try your hand at growing your own carnations in Colorado, here’s how to do it.

Edior's Note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the first name of the 29th president. His name was Warren Harding.