It was a hot Tuesday afternoon and Suzanne Simmons had just finished doing her routine chores on her 40 acre farm, outside of Lyons. Her alpaca and goats were fed, her chickens were roosting, and her fruit trees were watered. So Simmons went to take a shower.

When she stepped out of the shower, her house was filled with smoke. She looked out of her bathroom window and saw flames coming down the hillside towards her home. By the time she ran outside seconds later, her back pasture was ablaze.

“I had no time at all,” said Simmons, who has called Stone Canyon home for the last 24 years. “My two friends rushed over with a trailer and then the sheriff and fire department came and started banging on my door saying, ‘get out right now’ because the flames were literally on us…

But I said, ‘I'm not leaving until I get my chickens.’ And [the firefighters] went into my chicken coop with me, and three of them caught my chickens and put them into a dog crate for me.”

As Colorado and other parts of the western U.S. experience record-breaking heat and wildfires, more residents, like Simmons, are becoming ‘climate migrants’. In 2023, climate change-related disasters — like wildfires, hurricanes, and floods — displaced more than 2.5 million Americans.

The Stone Canyon Fire that displaced Simmons, albeit temporarily, was one of three wildfires that burned across Colorado’s northern Front Range in July, and the only one to result in a death. The wildfire burned for almost a week, killing one person and destroying five structures, including two of Simmons’ neighbors’ homes — less than half a football field away from her property. Simmons said she believes in addition to the tireless work of the wildfire crews, the reason her house didn’t face the same fate is because her house is made out of steel-siding as opposed to wood.

For the last 8 years, Simmons — who is an internal medicine doctor at Longmont United Hospital — said she has kept a ‘go bag’ next to her front door “because of all the fires” — which is understandable as the top three most destructive fires in Colorado have occurred in the last decade, according to the Division of Fire Prevention and Control.

In her bag were a few clothes, her passport, her stethoscope, and her hospital badge so she could get to work. As she ran into her smoke filled house to grab the bag, Simmons took one last look around her home.

“I think it’s something we all wonder,” she said. “I had literally five minutes. What could I grab in those five minutes?”

Her house was filled with a lifetime of memories and prized possessions — her complete Oxford English Dictionary collection, photos of her kids and grandkids, her beloved grand piano — but in those minutes, Simmons grabbed her grandmother’s antique teapot and pink satin kerosene lamp that were sitting on the top shelf of her china cabinet. She wrapped the antiques in a goose-down parka, threw her go-bag in the car, and fled down the mountain with her animals.

In a matter of minutes, Simmons' property had been transformed from a grassy hillside with acres of green pasture — surrounded by miles of sagebrush, wildflowers, cacti and running trails — to what she describes as looking like “Mars”. The fire scorched everything — from the Blue Glow Globe Thistles that lined her pathway right up to her front door, to melting her greenhouse and window panes into ash and molten glass, to burning her hay barn from the inside out.

For days, Simmons didn’t know whether she would have a home to return to.

Authorities still do not know what caused the fire, which burned over 1,500 acres, but suspect it was ‘human-caused’.

A few miles away from where Simmons was fleeing down Stone Canyon Road, Mysti Tatro was just arriving to work at Greenwood Wildlife Rehabilitation Center.

“I actually showed up late to work that day,” said Tatro, who is the community relations manager of the center. “I had some things to do in the morning and I was texting my boss after I arrived; ‘hey, do you know there's a fire behind us?’ And she said, ‘I know there's the Alexander Fire.’ And I told her, ‘no, no, it's right behind us.’”

After she notified her boss and the rest of the staff that the Stone Canyon Fire — not the Alexander Fire 10 miles north — was rapidly approaching the Center, Tatro said the Center staff started to come up with an evacuation plan.

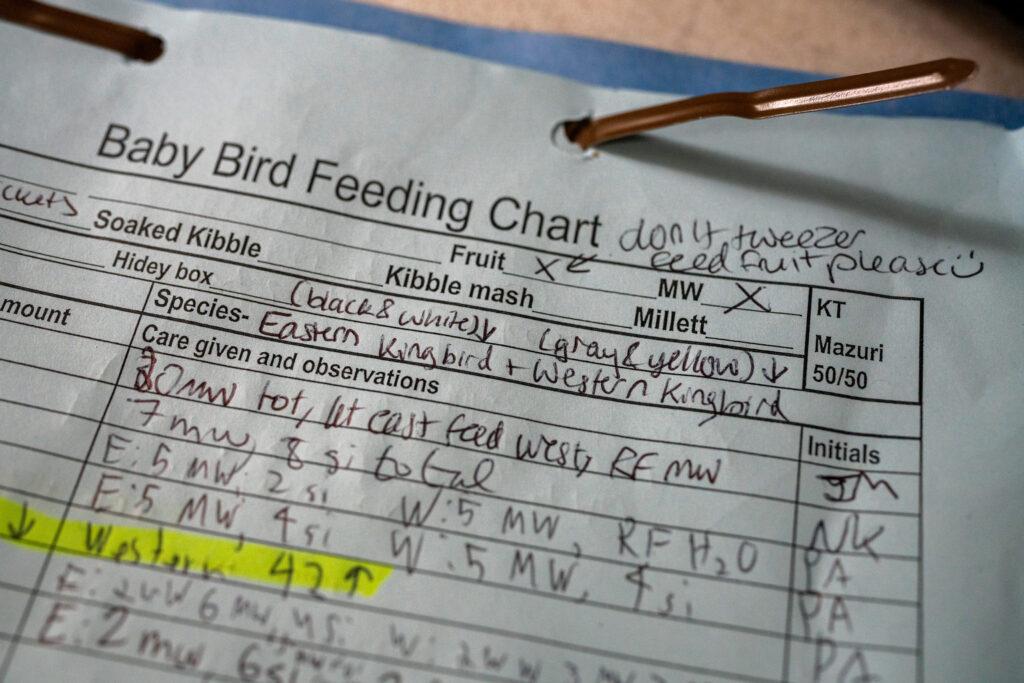

Which is not an easy feat when you have 600 wild animal patients — from hummingbirds to rabbits — and only a dozen trained staff. The staff loaded the animals individually into carriers and then transported them in their personal vehicles, a few miles away to a temporary shelter run by a trained wildlife caretaker.

“It was very stressful,” said Amanda Manoa, the head animal care supervisor of the Center. “We had such great support at the evacuation site. I think if we didn't have that, I would be going much crazier than I am now.”

As they were evacuating, Manoa said they were still receiving wildlife intakes — everything from a marmot with a peanut butter jar stuck on its head, to an orphaned swallow. The Greenwood Wildlife Rehabilitation Center is the largest, non-species-specific rehabilitation center along the front range. So they only shut their doors once all of the animals were safely evacuated.

“With the amount of wildlife we take and the amount of people we talk to and help through these situations, to not have anyone in this area would be really, really hard for people,” Manoa said. “We have already heard from a few local rehabilitation centers that the uptick that they saw [when we were closed] was a little hard on them.“

New climate migrants

The Stone Canyon Fire forced thousands of residents — everyone from long-time homeowners, like Simmons, to business owners, to even the mayor of Lyons, Hollie Rogin, and her family — to evacuate.

And Jonna Yarrington, a professor of Anthropology at Colorado State University, said she’s not surprised about the scale of the evacuations. In the last few decades, more people have been moving to mountain towns.

Yarrington has spent her career studying the impacts of climate change on human populations. And up until a few years ago, her research primarily focused on coastal communities along the Chesapeake Bay.

“A lot of people like to say that climate migrants are on the frontlines on the coasts, but that's not at all true,” said the professor. “It's not just the coastal people who are being affected by climate change because climate change is a global thing.”

According to Yarrington, who moved back to Colorado after recognizing a need for climate migration research in the mountains — Colorado and the mountain West are equally susceptible to climate change disasters; like wildfires, flooding, and drought. In her experience, she said she has seen people move further inland from the “sinking” coastlines, to “reinvest in a new area that is less risky” but to her, the question is: “is it?”

“It might be a less imminent risk, but it's just another kind of gamble that you're taking,” she said. “It's like when is the fire going to come or when is the flood going to come? What's the hazard in this part, in this region?”

But Yarrington’s work is not easy. First, it’s hard to measure and collect data on people who are migrating away and towards disaster prone areas. Secondly, there’s a lack of interest and therefore a lack of funding and data on climate change driven human migration patterns — something Mike Chard, the Director of the Office of Disaster Management for the city and county Boulder, knows a lot about.

Latest news on Colorado wildfires

- Alexander Mountain fire: State and feds marshal resources to fight large wildfire burning near Loveland

- Stone Canyon fire: Firefighters work overnight to contain fire burning near Lyons

- Quarry fire: Wildfire burning in south Jefferson County triggers evacuations near Deer Creek Canyon

- Lake Shore fire: Residents evacuated in Boulder County as fourth wildfire erupts in northern Front Range

- How to make an evacuation plan for fires, floods and other Colorado disasters

“I think the disasters that we've had in Boulder County, we get hit pretty hard,” Chard said. “If you're affected by a disaster, your house burns down, gets flooded, you then experience the insurance gap and either you're insured to build back or you're not. And that becomes, I think, a tremendous factor in determining who stays in the community or not.”

But according to Chard, who had a 27-year career fighting fires in Boulder County before working for the county’s Office of Disaster Management, some of the biggest issues in navigating wildfire risk and management are: not having enough data on how many people are moving to wildfire prone areas, more demand on disaster managers as wildfires become more frequent, and the socioeconomic status of the communities affected.

And Yarrington said the answer to this lies with policymakers.

“It's a huge question of ‘who's going to bear the burden of the risk? Who bears the cost of the damages?’ That's something that lawmakers are going to have to really grapple with,” she said. “And if they don't, then it will be the people. It will be the people who are living there and the people who decide not to leave. And that's what you see on the coasts is that the people who are the last ones there are bearing the brunt of the costs.”

The aftermath

On Aug. 4, local authorities announced that firefighting crews had completely contained the Stone Canyon Fire. All evacuation orders and road closures were lifted. But for Simmons and her neighbors, returning to Stone Canyon was only the beginning.

For over a week, Simmons and her animals were scattered between motels, the Boulder Humane Society, the Boulder County Fairgrounds, and the Jefferson County Fairgrounds. Now, she’s home — but while she said she feels “beyond grateful” she has a home to return to — she’s only beginning to set in how much damage the fire has left behind.

“I've already run up my credit card because I had to stay in a motel to be near the animals to check on them in Boulder,” she said. “...And the insurance company has been dragging their feet about sending someone out to look. And I said, ‘look, people, I’ve got to repair the fences and get a structure for my animals. I can't just leave it.’ And they said, ‘oh, we'll get someone,’ but they're dragging their feet.”

And according to Yarrington and Chard, this is a frustrating reality that many climate migrants face.

“[Climate disasters] make inequality worse because the people who are ill-equipped to deal with really bad events or losses are going to be pushed further down the ladder as this happens,” Yarrington said. “It affects people's mental and physical health. It affects their families, it affects their socioeconomic position in life, it affects their stability. And of course, those people who are already less stable or have less predictable income are going to be more affected.

“As a society, we have to decide who's going to be funding — that's what the insurance industry is having this problem with — who's going to be funding risk.””

For now, Simmons said she plans on rebuilding slowly; day-by-day.

Each day, she gives herself a new task: ordering air filters to clean the air in her smoke-filled home, replacing the charred fence lining her pasture, building a temporary A-frame shelter for her livestock, calling her insurance company. She said she keeps herself busy as she doesn’t have a choice, but also to keep her mind off of the devastation.

When she first returned home, she said one of the first things she noticed was how quiet it was — there was an evident lack of wildlife.

“I would say that wildlife in Colorado and the arid West in general have a pretty good relationship with wildfire and understand the dangers of wildfire,” Tatro said. “Animals seem to know what to do.”

But some weren’t so lucky.

Littered around Simmon’s property are the charred remains of small rodents and many rabbits. Simmons suspects that the fire burned through her property so quickly that it didn’t give the smaller animals time to escape.

In between chores, Simmons walks around her farm, adding tasks to her ever growing to-do list, occasionally stopping to drop a pile of hay or a few scorched apples from one of her fruit trees. She said she hopes the piles encourage wildlife to return to her property.

A few hours later, Simmons goes back outside to check on her offerings. The soot-covered apples are peppered with tiny teeth marks.

“Look, something came to eat those,” she said.

Correction (Aug. 14, 2024): An earlier version of this story inaccurately described the order in which rabbits are contained. They are lagomorphs.