At the Colorado School for the Deaf and Blind gym one Friday this spring, students stretched and warmed up for practice. Long goals sat at opposite ends of the floor.

After taking their places in front of the nets, each student took a hard rubber blue ball and started rolling it towards each other. With each roll, a bell rang. Warmups wrapped up with each player strapping on goggles with blacked-out lenses, and moving and feeling, on their hands and knees, along blue lines on the gym floor.

These athletes are members of the school’s goalball team. The sport was created for visually impaired athletes. It’s one of only two sports in the Paralympics that doesn’t have an Olympic counterpart, and teams will compete in the Paris Games starting Thursday.

Goalball has given young athletes like Zane Newton hope that he can compete on the international level one day. He said when he discovered that CSDB offered the sport, it was the best day of his life.

“I absolutely love it now because it's phenomenal,” said Newton, who is starting his sophomore year and began to lose his vision in 2022. “It's adaptive for what we need. It's absolutely amazing what they can do at a school where everyone is either blind or visually impaired and still make things accessible to us.”

Fourteen middle and high schoolers played goalball at CSDB this past year.

“It's been great to see the explosion of the kids being interested in goalball and wanting to get out there,” said Amanda Padilla, a program assistant at CSDB and one of the goalball team’s coaches. “They've just gotten more eager about it, and it's been great to watch and be a part of.”

The coaches admit the sport can be both fun and painful at times, depending on the level of competition. Jessica Rawlins just completed her first year coaching and works at CSDB for over 15 years. She said it takes a lot of bravery to play the sport.

“Basically for me, being a sighted person, going out and practicing with them or playing, it's very daunting,” Rawlins said. “I think that we can orient ourselves on the court a little better. We have a visual imprint of it when a lot of our students don't have that.”

How and when was goalball created?

Goalball was invented by Austrian Hanz Lorenzen and German Sepp Reindle in 1946.

Similar to Dr. Ludwig Guttmann’s use of sports as a means of rehabilitation at the Stoke Mandeville Hospital that led to the Paralympics, the two created the sport to help rehabilitate war veterans who returned with visual impairments.

It was featured as a demonstration sport at the 1972 Summer Paralympics in Heidelberg, Germany, before making its official Paralympic debut at the 1976 Summer Games in Toronto. Only men played at first.

Austria beat West Germany, 4-2, for the first Paralympic gold medal. Women first competed in goalball at the Paralympics in 1984.

The United States men’s goalball team earned its first Paralympic medal, a silver, at the 1980 Games in Arnhem, Netherlands.

Both USA teams struck gold at the 1984 Games in front of a small crowd in a gym located on the campus of Nassau Community College in New York. Together, the teams have earned a combined 12 Paralympic medals in goalball.

How do you play goalball?

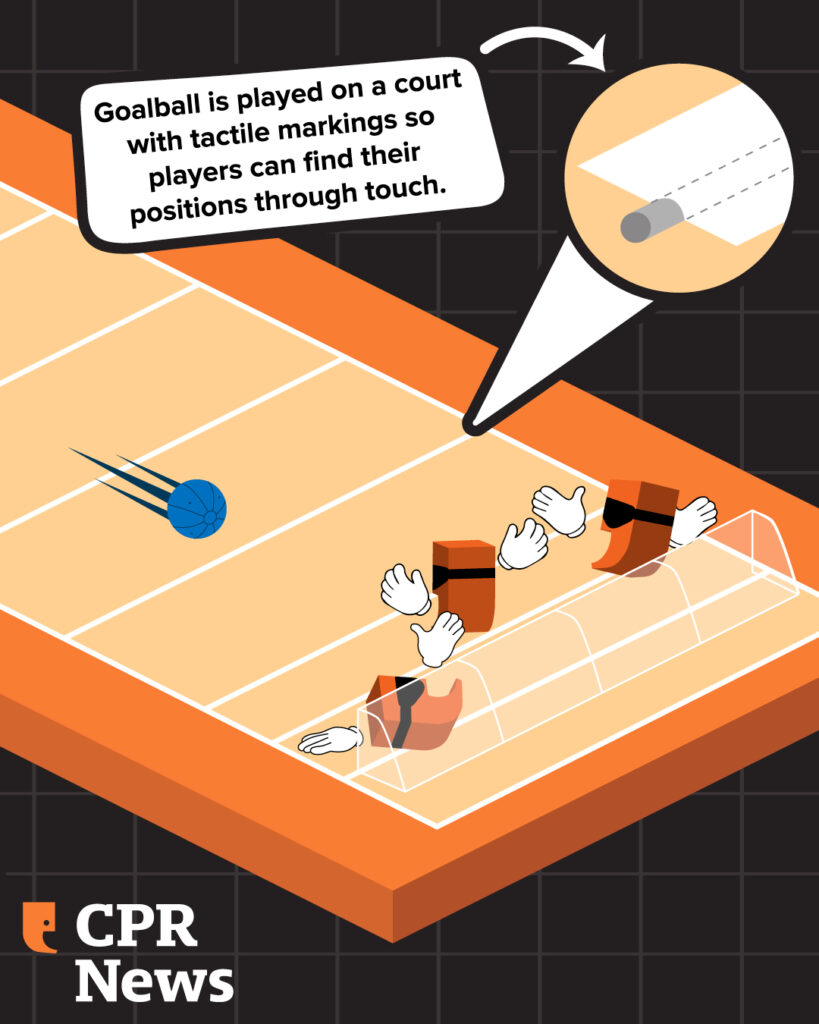

Goalball is played on a rectangular court roughly the size of a volleyball court. The court is measured in sections with tape with a cord running underneath, which players feel before a match in order to orient themselves and locate areas on the court.

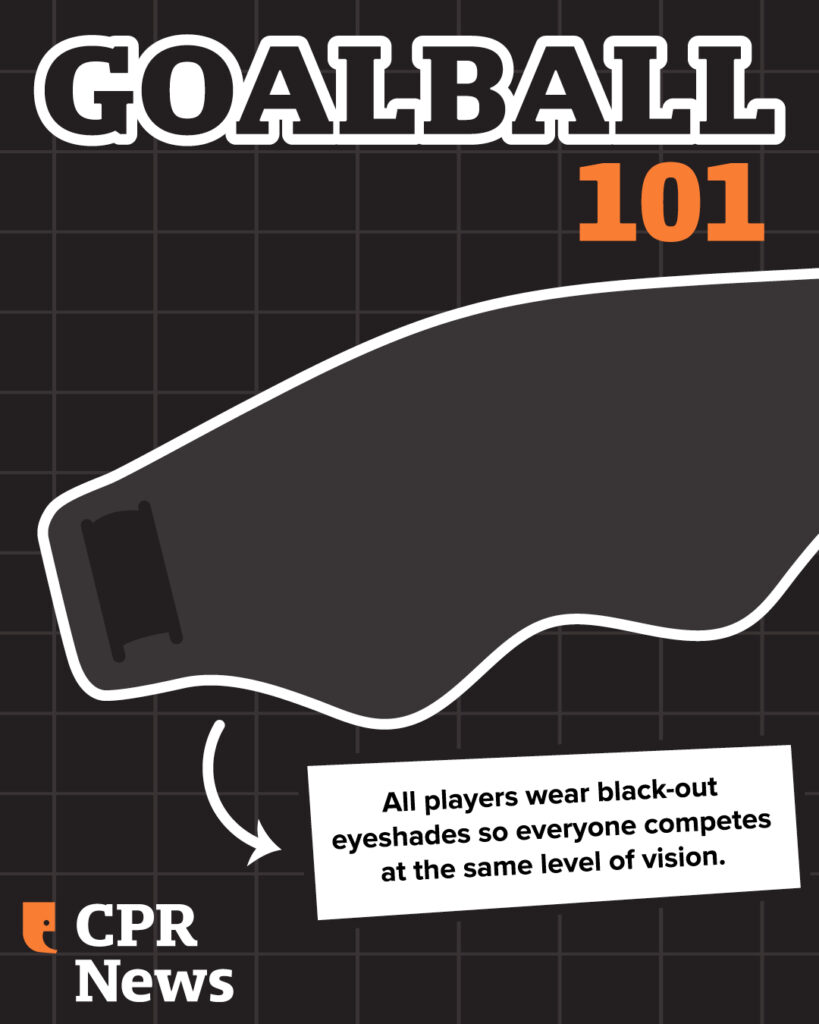

Each player must have their eyes covered in gauze patches or something equivalent before putting on eye shades that are completely blacked out. Eye shades are necessary because there is a spectrum of visual impairments. With the shades on, all players have the same level of visual ability: none.

There are three players on the court for each team at a time. A player rolls the ball to try to score a goal. The defenders use their hearing to locate the ball and stop it by diving sideways, forming a barrier with their bodies.

When the game starts, the referee quiets the entire gym, so the players have a better chance to hear the ball.

The ball itself looks soft like a dodgeball but is actually made of molded rubber, which makes it hard. Inside the ball are two bells.

Goalball can be a brutal sport

Rawlins, one of the coaches at CSDB, said the sport can be brutal.

“The balls they use are very sturdy, they are hard, and depending on the level you’re playing at, they’re served very fast,” she said.

Trying to stop the ball can be difficult, too. Newton has an added challenge: his cerebral palsy makes it difficult to dive to his left.

“What I'll do is I'll always dive to my right, but then I'll slide whichever way the ball's coming,” Newton said. “So, even if it's coming on my left side, I dive to my right and then slide, or slide and then dive down onto my side, to stop the ball. And that's just what I've found is the fastest and easiest way to do it for me.”

The speeds of the ball rolls can vary depending on the level of competition. In the Paralympics, the ball can even bounce over players.

Padilla said that some players don’t even fire the ball down the court.

“Some people are skilled at throwing a silent ball, so it goes very slow, but you can't hear the ball, the bell in it. And so people don't know where to block,” Padilla said. “It's very hard to do that. And one of our former coaches used to be on our goalball team at CSDB, and he was very good at doing this little spin on the ball and you couldn't hear the bell.”

Like any sport, it 'just takes practice'

On the spring day at practice, no one was more skilled at throws than Tayler Moses. She would gently push the ball forward. Between breaks and after practice, she kept working on her skills by herself. She said the sport helps her relieve stress.

“It helps me just kind of put my day behind me and power through it," Moses said. "I do the extra practice after everyone's gone because it gives me that extra time to just release all my tension throughout the day and all my emotions.”

Moses was born with Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), which is a rare type of inherited eye disorder that causes severe vision loss at birth. Moses described it as her body attacking her eyes. Those with LCA typically go blind by their late teens. Fifteen genes have been found to cause it when they are mutated. One of those genes is Retinal Dehydrogenase 12 or RDH12, which recycles molecules that are important in the eye’s ability to detect light. Without a functioning RDH12, the cells of the retina die.

Her mother got her involved with goalball when she was registering for classes at CSDB and she has enjoyed it ever since, even though she has stopped attending the school.

“It's really difficult at first, but you will get the hang of it,” Moses said. “And the thing is, it just takes practice.”

Colorado School for the Deaf and Blind even has a Paralympian on staff

Newton said goalball comes up when he visits his orientation and mobility instructor Robin Tueting.

She’s not just an instructor at the school. The Michigan native has won numerous medals in the sport — including gold and silver medals in the Paralympics.

Tueting was born with ocular albinism, which results from the inability of pigment cells in the eyes, especially the iris and the retinal pigment epithelium, to produce pigment.

She has a lot of functional vision, and in general, her guess is that people don’t know that she’s legally blind unless she tells them. But as a kid, she didn’t think she had what it takes to make sports a profession.

“I kind of grew up as a little kid on the playground playing sports with friends, but once everybody's hand-eye coordination kicked in and mine did not kick in, I kind of just thought I wasn't going to get to be an athlete,” Tueting said.

At a summer camp sponsored by the Michigan Blind Athletic Association when she was 14, Tueting learned about goalball. She fell in love with the sport.

“I think I really gravitated towards it right away because it's such a physical sport,” Tueting said. “It's not just a let's catch this ball and then throw, you're like throwing your body on the ground. You're letting this ball hit you. It's very physical, it's very aggressive and I just really loved that. I love the aggression, I love the competition.”

When she found out that it was a Paralympic sport, she began training and playing on local teams in regional and national tournaments. After being scouted, she was invited to U.S. national team training camps. Tueting’s first international competition was the 1998 World Goalball Championships in Madrid, Spain. Team USA won the bronze medal that year. Tueting said her experience was amazing.

“There's so much pride involved in wearing a jersey with your flag on it, wearing that USA across your chest,” Tueting said. “So, I feel like I was really still a new player to the sport and had a lot to learn. But I just, oh my gosh, it was so amazing!”

Her first Paralympics came in 2004 in Athens. The United States lost to Canada, 3-1, to take the silver medal. Tueting appreciated the medal, but also said it was difficult.

“It's still amazing to be on that podium, but it was a little bit of a heartbreaker for us to come up short that time around,” Tueting said.

Tueting and the USA achieved Paralympic glory at the following Games in Beijing, overcoming a Chinese host team that had been dominant. The gold medal match culminated in a thrilling comeback win, 6-5, for the U.S.

“It was just a huge comeback to be able to win in their home basically with all of their fans in the stands. It was unbelievable,” Tueting said.

Tueting’s goalball career came to an end at the 2012 Games in London where the U.S. finished 12th. While that chapter of her athletic career came to an end, she started a new one in a different sport: roller derby.

“Since it's a sport where there's no ball involved, I was like, ‘Maybe I could do that. I could maybe play a sport with sighted people,’” Tueting said.

With a neighbor, she started skating with a team. “It was not something I was good at right away. I was not a great skater. It took me a while to learn how to skate to learn the rules of the game and how to process everything that was happening on the track.”

She describes the sport as “pandemonium,” “bananas,” and “action all the time.” But, says she can navigate through all the chaos well because everyone is close to each other. Like in her daily life, she suspects people don’t know she’s visually impaired during competition. She doesn’t volunteer the information because she doesn’t want anyone to prejudge her based on her disability.

“I don't want people to look at me differently. So, I want to skate. I want to be looked at as an athlete, not as a visually impaired person, per se,” Tueting said.

Yet, Tueting said being a visually impaired athlete had helped debunk a lot of myths about disabilities.

“There's definitely a misconception that if you're blind you can't see anything. And so a lot of people don't know that blindness is a spectrum and that there's visual impairment all the way to no light perception. Sometimes it's a bit of an education,” Tueting said.

Goalball also aims to bring people together

The CSDB goalball team has competed against teams from other states, and they have invited some members of the Colorado Springs community to try the sport.

Padilla said cadets from the U.S. Air Force Academy played against the CSDB team, and like most people who have never played before, they were lost on the court.

“One time they threw at someone else that was on their team pretty hard,” Padilla said. “And then, they kept throwing them at the bleachers because they just didn't know where they were facing and where to throw the ball.”

Towards the end of the school year this past spring, the student-athletes at CSDB faced the Colorado Springs Police Department in front of a packed gym. The match was close and the officers held their own, but CSBD won, 9-8.

After the match, officer Ruselis Perry said the sport was pretty difficult but very fun. The six-year veteran on the police force left the court impressed by the student-athletes.

“You do have to hone into your other senses and sometimes we take so much advantage of our sight that we don't really hone into other things, taste, feel, hearing,” Perry said. “And this one actually, you're really keying in on the hearing, the feeling and your equilibrium. You have to watch that. It is very interesting.”

For the students, who had been hungry to compete outside of a scrimmage, it was an exciting day.

“It was amazing just to be out on the court again, to play a team I’ve never played before, and to more importantly, beat them. Because it’s not something you do every day.” Newton said.

Goalball has allowed many young people to form Paralympic aspirations. Newton and Moses said they will both check out the sport during the Paris Games and hope to compete on that level someday.

“These guys can go 20 minutes without throwing out of bounds or goals, and it’s incredible. I don’t know how they do it,” Newton said. “So just watching them would help my understanding of the game – like, watching it so I can visualize what they’re doing that we’re not doing on the court because they’re much better than we are.”

When does goalball start in the Paralympics?

The first goalball match in the 2024 Paralympics is set for Aug. 29, with China vs. Japan in the men's preliminary round.

The U.S. women will not compete in the Games, but the first match for the U.S. men’s team is Aug. 30 against World Champion Brazil. The last time the two teams met was in the gold medal match of last year’s Parapan American Games. Brazil won 12-2.